S. Swift

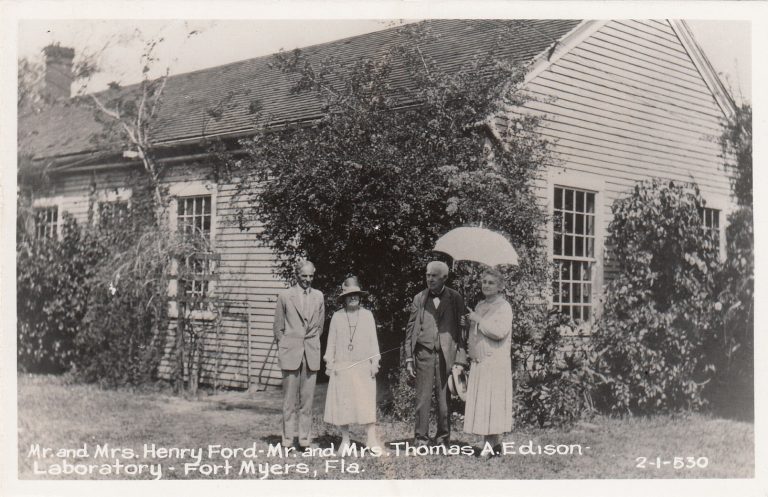

Thomas Edison and Henry Ford

In 1885, Thomas Edison and his friend and partner, Ezra Gilliland, traveled to the cattle-ranching village of Fort Myers, Florida. They were instantly enchanted and purchased 13½ acres. Edison designed a plan for two identical homes with gardens, and of course, a laboratory.

The area was virtually undeveloped so all the materials for the houses had to be shipped by sea. Consequently, a large dock extending far into the Caloosahatchee River was one of the first structures to be built. Gilliland sent the final plans to a company in Maine that specialized in cutting planks, boards, shingles, and windows marked for easy reassembly. To light his home, which he named Seminole Lodge, Edison brought chandeliers, among his first light fixtures, from his Menlo Park laboratory. Ironically, these were not operable until 1887 for the lack of a dynamo to power them.

Edison, a widower with three children, married Mina Miller in February 1886 and they honeymooned in Florida, but they did not return until 1901. It was then that they began their long local ties by investing in a local country club and assisting in starting a town library. Edison also began a tradition of arriving in Fort Myers near his February birthday and giving an annual interview to the press.

However, it was Mina, rather than her husband, who plunged deeply into community affairs. Her social calendar was filled with speeches on conservation, meetings, luncheons, and reading groups. She also managed the house, including the lush gardens. In 1929, Mina was interviewed by Marjory Stoneman Douglas for McCall’s magazine and Douglas was clearly impressed with Mina’s achievements as a social engineer.

Mina wanted women’s work to be valued and honored and sought to change the word “housewife” to “home executive.” The local newspaper noted “wives of great men usually are content to bask in the reflected glory that hovers about their husbands. An outstanding exception to that general rule is found in Fort Myers where many beneficial community activities receive an invaluable impetus from the leadership and active participation of Mrs. Thomas A. Edison.” But all that was in the future — in 1914 their adventure in the “jungle” was just starting.

In 1914, the Henry Ford-John Burroughs-Thomas Edison connection to Fort Myers began when 2,000 locals waited near the railroad platform with a brass band and 45 Ford cars. Burroughs, the famous naturalist, with Edison and Ford decided to go on a camping trip to an interior wilderness called Big Cypress. Initially their wives were excluded but at Mina’s insistence the entire party piled into five cars together for the expedition. There were no paved roads, much dangerous marshland, and snakes. Torrents of rain soaked the campers. However, the exploration made a big impression on the guests and was the first of many camping trips.

Just two years later, Ford (who had once worked for Edison and idolized him) bought a small bungalow near Edison’s Seminole Lodge for $20,000. (In contrast, a few months earlier, the Fords had moved into Fairlane, a 1,300-acre property in Michigan at the cost of $2.4 million.) Ford continued to visit Fort Myers annually until Edison’s death in 1931. Ford enjoyed walking — the master of the automobile walked the seven miles from the Punta Rossa dock to his new cottage.

By 1918, Edison’s Fort Myers lab was nearly abandoned and the dynamo was no longer needed because Seminole Lodge was now connected to the new Fort Myers electrical system. So in 1926, Ford proposed, over Mina’s objections, to dismantle the lab and move it to Ford’s new museum in Michigan where he had already assembled several of Edison’s former properties. These became the foundation of his Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan. In exchange for the 1886 lab, Ford built a new facility at Seminole Lodge for Edison’s rubber research.

Edison had a particular fondness for baseball. In 1926, he went to the spring training of the Philadelphia Athletics in Fort Myers and took two pitches from Kid Gleason, with manager Connie Mack catching. Edison was able to hit the second pitch and a local newspaper crowed that Edison had a better batting average than Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb.

The next year, Edison took pitches from Ty Cobb and not only was he able to hit his pitch but he knocked Cobb off his feet. He invited the entire team, which included Cobb, Jimmie Foxx, and Lefty Grove, to Seminole Lodge in 1927 and gave them a personal tour. Even in 1931, despite the Depression and in ill health, Edison attended an Athletics game. When he arrived, the players stopped the game with the support of the deafening applause of the crowd.

Toward the end of his life, the citizens of Fort Myers wanted to honor Edison by naming a new bridge in his honor. On February 11, 1931, his 84th birthday, Edison agreed to cut the ribbon for the dedication of the bridge before a crowd of 10,000. No lights had been considered in planning the construction of the bridge.

In 1935 Ripley’s Believe It or Not received an anonymous postcard of the bridge with the comment that the bridge dedicated to the inventor had no electric lights on it. Ripley’s in turn published a cartoon of the bridge with a caption “The Thomas A. Edison Bridge — Fort Myers, Florida — Has Never Had An Electric Light on It.” This embarrassment prompted the city to raise funds for 54 lights that were first turned on by Edison’s son Charles on November 25, 1937, a final fitting tribute by Fort Myers to their famous first snowbird.

Thank you for this insightful bit of history. It shows the human side to the Edison & Ford relationship in a way that I had not seen when we visited the site. Also, the baseball connection is neat and probably had a link to the eventual Spring Training locations.

Very interesting and enjoyable article.

I never knew that Edison knew Ford. And kudos to the second Mrs. Edison:)