Judi Kearney

Proclaim Liberty

Throughout the Land...Literally!

My title is part of the inscriptions on the Liberty Bell, and there were times when the Liberty Bell left the security of its home in Independence Hall, and went on a road trip… or two… to proclaim liberty. This is what I’ve been able to learn about the travels of America’s most recognized and beloved symbol.

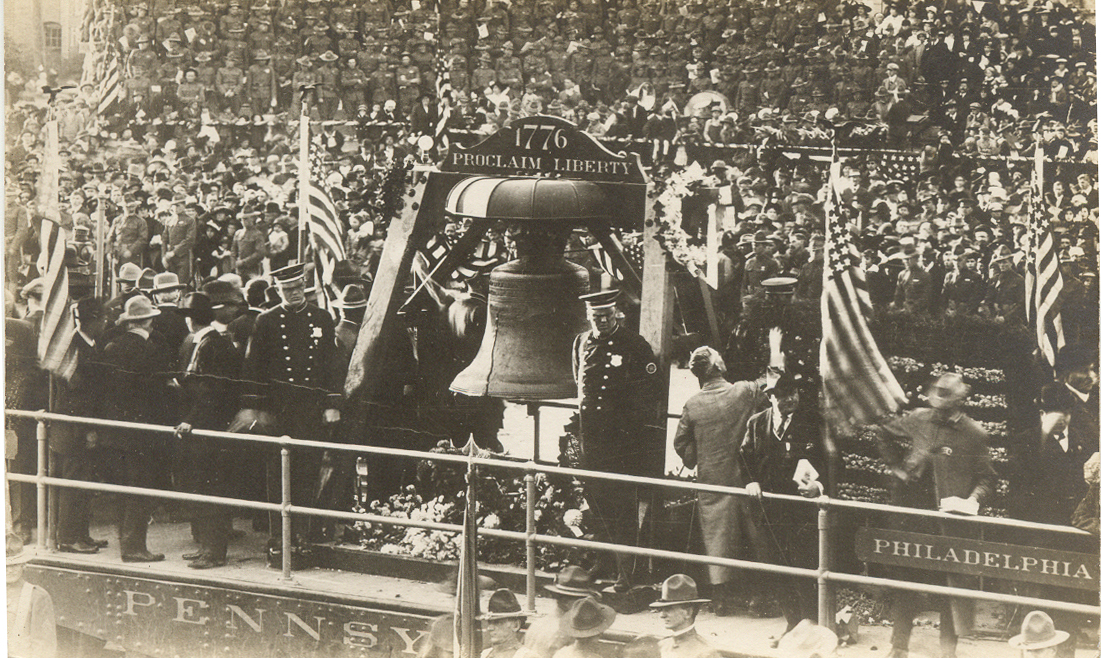

After the divisive Civil War, Americans began to look for something – a symbol that would unify a country that had been divided by ideals and beliefs. The flag – the beautiful stars and stripes became one such symbol. Nearly everyone possessed a flag – flags were flying everywhere. The Liberty Bell became another, but so many citizens had never seen the Liberty Bell, it was decided that the bell would travel throughout the country in an ongoing effort to heal the wounds of war.

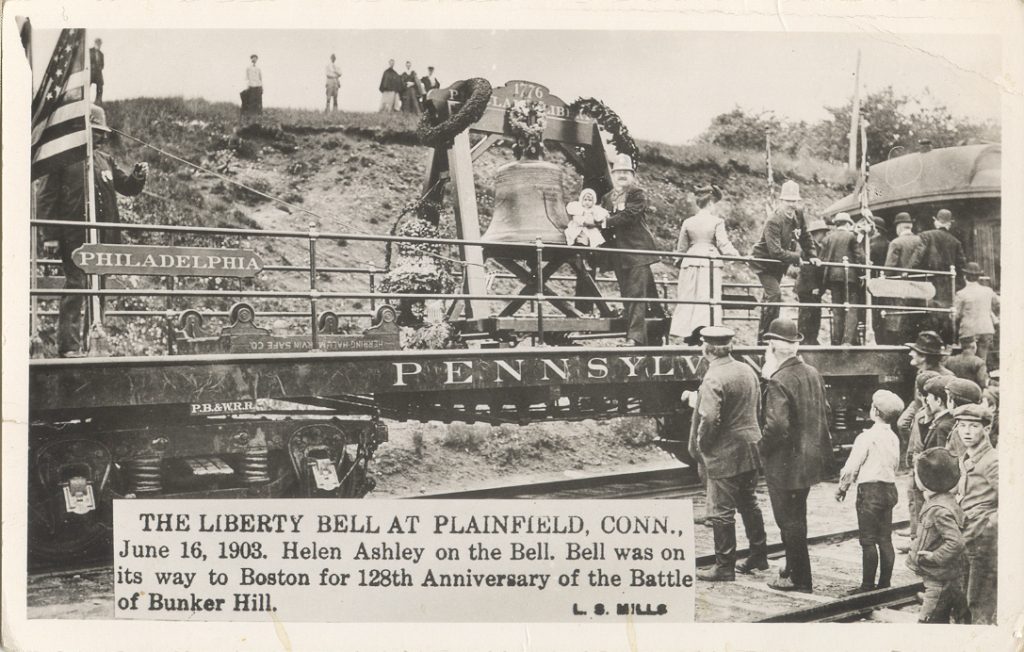

Starting in the 1880s, the bell traveled to cities throughout the United States. Between 1885 and 1915, the Liberty Bell made seven trips to various expositions and celebrations. In 1885, the bell traveled to New Orleans for the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition. In 1893, the bell traveled to Chicago for the World’s Columbian Exposition. In 1895 and into 1896, the bell went to Atlanta for the Cotton States and International Exposition. In 1902, it was displayed at the Inter-State and West Indian Exposition in Charleston, South Carolina. In 1903 the bell went north to Boston to commemorate the 128th anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill.

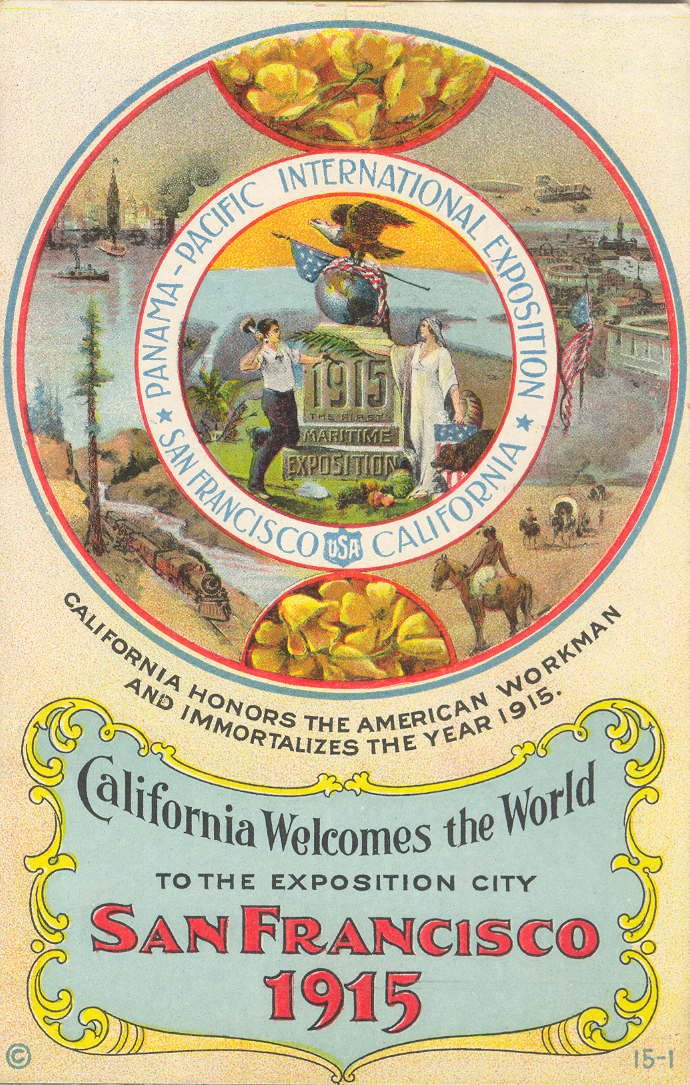

Then in 1904 the bell was an important part of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (also known as the St. Louis World’s Fair) in Missouri. It is estimated that more than 200,000 people came to see and touch the Liberty Bell when the train stopped in Indianapolis during its trip to St. Louis. The bell’s final road trip (1915) was across the country to the Panama-Pacific Exposition, and then south to San Diego for the Panama California Exposition.

Each time, the bell traveled on a flatbed train car, stopping in small towns along the way so that local people would have an opportunity to view it. (A few of my postcards are “homemade” by those local folks who were fortunate enough to see the bell as it passed through roadside America.) By 1885, the Liberty Bell was internationally recognized as a symbol of freedom and a treasured relic of independence. In early 1885, the city of Philadelphia, who claimed ownership of the bell, by right of its home in Independence Hall, agreed to let it travel to New Orleans for the World Cotton Centennial Exposition. Large crowds mobbed the bell at each stop. In Biloxi, Mississippi, the former president of the Confederate States, Jefferson Davis came to the bell and spoke on the importance of paying homage to it, and urged national unity.

During its 1893 trip to Chicago for the World Columbian Exposition, it was the centerpiece in the Pennsylvania Building. On July 4, 1893, in Chicago, the bell was honored with the first performance of The Liberty Bell March, conducted by composer John Phillip Sousa.

Meanwhile, back home in Philadelphia, city officials began hearing about problems when the Liberty Bell traveled. It returned from the Chicago Exposition with a new crack; and thereafter, each request for travel was met with  increasing opposition. Philadelphians were also informed that the bell’s private watchman had been cutting off small pieces for souvenirs, and selling them for a handsome profit, resulting in the city placing the bell in a glass-fronted oak case in the Assembly Room of Independence Hall. In 1898, it was taken out of the glass case and hung from its yoke again in the tower hall of Independence Hall, a room which would remain its official home until the end of 1975. A guard was posted to discourage souvenir hunters who might otherwise chip at it.

increasing opposition. Philadelphians were also informed that the bell’s private watchman had been cutting off small pieces for souvenirs, and selling them for a handsome profit, resulting in the city placing the bell in a glass-fronted oak case in the Assembly Room of Independence Hall. In 1898, it was taken out of the glass case and hung from its yoke again in the tower hall of Independence Hall, a room which would remain its official home until the end of 1975. A guard was posted to discourage souvenir hunters who might otherwise chip at it.

By 1909, the bell had made six trips, and not only had the cracking become worse, but souvenir hunters had deprived it of over one percent of its weight. In 1912, the organizers of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition presented a petition, signed by 500,000 California school children, requesting the Liberty Bell for the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. The city was reluctant to let it travel again, but finally decided to let it go, since the bell had never been west of St. Louis, and it was a chance to show it to millions who might never have the opportunity to view it.

In 1914, fearing that the cracks might lengthen during the long train ride across the country, the city installed a metal support structure inside the bell, called the “spider.” In February 1915, the bell was tapped gently with wooden mallets to produce sounds which were transmitted to the fair as the signal to open it, a transmission which also inaugurated transcontinental telephone service.

Some five million Americans saw the bell on its train journey west. It is estimated that nearly two million kissed it at the fair with an uncounted number viewing it. Traveling across the heartland of the America, the train made frequent stops, where large crowds of citizens gathered to see and touch this iconic symbol of America. A beautiful photo essay was created by W. S. Trinkle, documenting the Liberty Bell’s journey from Philadelphia to San Francisco and its return in 1915.

The photographer’s father, W. W. Trinkle, M.D., was on the Common Council of the Joint Special Committee that helped plan the events and to create, for profit, a photo album of the Liberty Bell on its journey.

There are only five of these Trinkle albums known to exist. The postcards I’ve been fortunate enough to collect are for the most part unmarked. I have been unable to determine if any of them are part of the famous Trinkle Album. I’ve been lucky enough to find a card showing the train stop in Elizabethtown, Cleveland, Ohio; Lima, Ohio; Portland, Oregon; and several from Seattle, Washington. On the bell’s return trip to Philadelphia – a trip that took a more southern route across the country, I found one from the stop in El Paso, Texas, but several are unidentified locations.

Since the bell returned from its 1915 road trip, it has been moved out of doors only five times: three times for patriotic observances during and after World War I, and twice as the bell occupied new homes in 1976 and 2003. Chicago and San Francisco had obtained the presence of the Liberty Bell after presenting petitions signed by hundreds of thousands of children. Chicago tried again, with a petition signed by 3.4 million school children, for the 1933

Century of Progress Exhibition and New York presented a petition to secure a visit from the bell for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, but both requests were turned down, citing safety and protection concerns.

In 1924, one of Independence Hall’s exterior doors was replaced by glass, allowing some view of the bell even when the building was closed. When Congress enacted the nation’s first peacetime draft in 1940, the first Philadelphians required to serve took their oaths of enlistment before the Liberty Bell. Once the war started, the bell was again a symbol, used to sell war bonds. In the early days of World War II, it was feared that the bell might be in danger from saboteurs or enemy bombings, and city officials considered moving it to Fort Knox to be stored with the nation’s gold reserves. The idea provoked a storm of protest from around the nation and was abandoned. Officials then considered building an underground steel vault below the normal displayed area where it could be lowered if necessary. The project was dropped when studies found that the digging might undermine the foundations of Independence Hall.

The bell was again tapped on D-Day, as well as in victory on V-E Day and V-J Day.

Today, the Liberty Bell is housed in its own special exhibit hall on Independence Square. It is viewed and revered by millions of visitors each year.

In 1950, the United States Department of the Treasury, assisted by a number of private companies, chose the Paccard Foundry in France, to cast 55 full-sized replicas of the Liberty Bell. These were shipped as gifts to each state and territory of the U.S. and the District of Columbia, to be displayed and rung on patriotic occasions. This was the kick-off for a savings bond drive held from May 15th to July 4th, 1950. The slogan was “Save for Your Independence.”

Do you know where the replica bell resides in Pennsylvania? If you search Postcard History you can learn the answer.

Judy, very nice article. Would love to know more about those Trinkle albums. I have some photos that I believe are from one that was taken apart. Can you email me? Also on the return trip home from Chicago in 1893 the bell was brought back to Allentown where it had been hidden during the revolution. They brought it right into the downtown via the trolley tracks to Zion’s Reformed Church.

I never knew the Liberty Bell travelled outside of Philadelphia. Thanks for this article!