Bill Burton

“They ran off to

Gretna Green to get Married”

In 1753, The Marriage Act was passed by the British Parliament. It was aimed to regularize the process of marriage by requiring that no one could marry except in Anglican Church ceremony following the announcement of banns at the couple’s home parish or obtaining a church-issued license.

These changes in marriage law had several effects. To go through the banns or license procedure took time. By making the established Church of England the sole site for marriage, additional time was added. And incidentally, parental consent was required for anyone under 21 to marry.

But there was a gigantic loophole — the Marriage Act only applied to England and Wales. Scotland didn’t have an established church but rather a national church, the Church of Scotland, which meant that there were no religious-oriented laws for marriage, leaving that to civil authorities. Even so, marriages in Scotland were recognized everywhere in the United Kingdom.

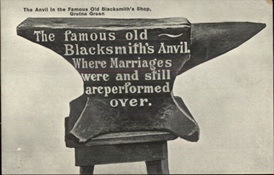

The most direct north-bound coach road between London and Edinburgh crossed the Sark River, which formed the border between Scotland and England. The small village of Gretna Green was at the Scots end of the bridge. And a blacksmith shop was the first building in the village.

Scottish law allowed “irregular marriage,” demanding only a declaration by the couple in front of two witnesses with no waiting period, no residency requirement, and only that the husband be at least 14 and the bride, 12. The blacksmith thus could perform a marriage ceremony, using his anvil as a rostrum, in a matter of minutes.

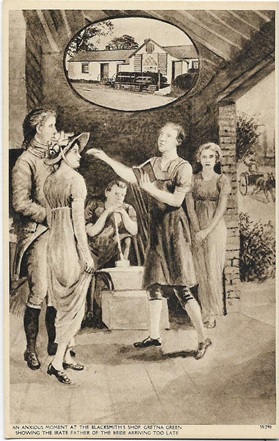

For 100 years, until 1856 when the law changed to require residence of 21 days prior to the ceremony, a “Gretna Green marriage” was synonymous with elopement. Tales of young lovers (and not-so-young lovers) rushing ahead of hot pursuit by angry fathers were a staple of romantic lore and literature. Jane Austin used Gretna Green elopements in Pride and Prejudice and Love and Freindship [sic].

Over time, other venues for these weddings grew up in the village. A hotel and several inns were built and the other blacksmith shop in the village added the service. Interestingly, all of these places performed their rituals over a blacksmith’s anvil.

With the 1856 change in the law, the wave of elopements began to ebb. Still, as late as 1940, when Richard Rennison ended his 14-year time as the “anvil priest,” he had recorded 5,147 marriages in his register.

Today, Gretna Green is a booming “destination wedding” site. The company that operates it offers not only complete wedding packages but also souvenir keyrings, pins, and charms in gold, silver, and brass. The original blacksmith shop has since 1885 been a family-owned visitor center, a “Visit Scotland Five-Star” building that attracts thousands of non-eloping visitors every year.

Not surprisingly, “Gretna Green” became a catchphrase for elopements and quickie weddings in America. Not counting Reno and Las Vegas, Nevada, which came later, two of the more well-known sites for these marriages were Aberdeen, Ohio, and Elkton, Maryland.

Not surprisingly, “Gretna Green” became a catchphrase for elopements and quickie weddings in America. Not counting Reno and Las Vegas, Nevada, which came later, two of the more well-known sites for these marriages were Aberdeen, Ohio, and Elkton, Maryland.

Aberdeen, as this postcard shows, was self-promoted as “The Gretna Green of America.” It would seem that Cincinnati, bigger by far than Aberdeen and better-located closer to Indiana and Kentucky than Aberdeen, was a more likely site for elopements from these states. And it is true that it was. But Aberdeen has something else (besides being at the other end of the bridge from Maysville, Kentucky and close to West Virginia).

Two successive Aberdeen Justices of the Peace — Thomas Shelton who conducted the marriage business from 1855 until his death in 1870, and Massie Beasley, whose tenure ended in 1892 — between them are credited with marrying an enormous number of couples. (Newspaper and historical society accounts are all over the place, some saying 30,000 and others hovering around 11,000.)

Their forte was weddings without paperwork. Both men devised their own certificates, testifying that they had married the couple legitimately in the presence of witnesses. They are said to have sometimes married 15 couples a day.

Shelton didn’t handle even this paperwork well. With the county recording office 40 miles away, over time two or three generations did not have their marriages officially recorded. The wheels came off after the Civil War when widows and children of veterans were applying for pensions. Evidence of marriage was required and there wasn’t any. It got so bad that the state of Kentucky passed a law retroactively legitimizing all of Shelton’s marriages.

Massie Beasley was something else. While Shelton charged moderately for a ceremony, Beasley is said to once have charged $40 to marry two New Yorkers. As a souvenir of each ceremony, Beasley presented the newlyweds with a photograph — of himself.

In 1913, four East Coast states, Pennsylvania, New York, Delaware, and New Jersey imposed various waiting periods before marriage.

Until then, Delaware had the least restrictive rules. Its largest city, Wilmington, with its quick and easy train ride from Philadelphia, New York, and New England, was the “Honeymoon Express” destination of choice.

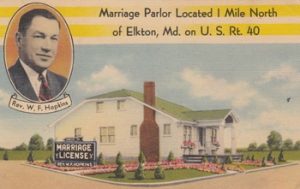

The stop past Wilmington was the Cecil County seat of Maryland, Elkton. And Maryland hadn’t joined the frenzy.

Elkton developed a very businesslike attitude about these marriages. Cabbies and for-hire cars met each train, ready to take the lovers to the marriage parlor that paid them to deliver customers. A license was available on the spot and the ceremony followed quickly. There was only one requirement — that the marriage had to be performed by a clergyman. One local newspaper reported that Elkton was holding one marriage every 15 minutes, some 12,000 every year.

Alas, the end came in 1938, when Maryland’s 48-hour waiting period law took effect. From an official total of 16,054 marriages in 1937, Elkton had only 4,532 in 1938. A law allowing the County Clerk to perform weddings didn’t help the wedding parlors.

The last of its kind, the Little Wedding Chapel on Main Street, closed in 2016 when its banker foreclosed its mortgage.

Bill Burton began collecting Ossining, New York postcards when he lived in that Hudson Valley town. His collection expanded, of course, to include his college, the neighboring towns, and places where he and his wife traveled. In retirement, he's refocused on Delaware and the DelMarVa peninsula towns, but he’s just as likely to be found parked in front of the 25¢ boxes at shows.

This was a very interesting article. Elkton MD had long been known as a quick place to get married for people in Delaware.

Although I was born in Ohio and lived there until I was 41 years old, I had heard of Gretna Green’s reputation, but not Aberdeen’s.