Bill Burton

They Were Champion Boxers Once,

and Restauranteurs Too

James Montgomery Flagg’s painting reproduced on a postcard that was handed out at Dempsey’s restaurant. The original hung in Jack Dempsey’s restaurant until the restaurant closed, when it was donated to the Smithsonian.

Jack Dempsey rose to fame after World War I. His relentlessly aggressive fighting style aptly gave him the nickname “The Manassa Mauler.” Born dirt poor in 1895 into a family that eventually settled in Salt Lake City, he dropped out of school at age 16 to live on his own.

To support himself, Dempsey would approach saloons and offer to fight anyone, saying “I can’t sing and I can’t dance, but I can lick any [SOB] in the house.” He made money on the bets that were made. He won many more fights than he lost and was soon seen as a serious prizefighter. By 1919 he had fought many ranked contenders and lost only once. He won the opportunity to fight for the heavyweight championship against the reigning champion, Jesse Willard, who was five inches taller and over 55 pounds heavier.

Dempsey knocked Willard down seven times in the first round, inflicting what one newspaper dubiously reported as “a broken jaw, broken ribs, several broken teeth, and a number of deep fractures to his facial bones.” He was now the World Heavyweight Champion. And he was also incredibly famous.

During the next seven years, Dempsey defending his title five times. Between fights, he toured the country making money from product endorsements, public appearances of all sorts, even movie roles. His manager, Jack Kearns, accumulated this money and by the time he fought Gene Tunney in 1926, Dempsey was a wealthy man.

Dempsey lost the Tunny fight in a unanimous decision. A year later, they fought again (a fight famous as the “Long Count Fight”) and again Dempsey lost. it was Dempsey’s last championship fight.

For almost a decade afterwards, Dempsey roamed the country, fighting exhibition matches and making public appearances. He made even more money for appearing in a 1933 MGM movie The Prizefighter and the Lady, where he played the referee.

In 1935, he opened Jack Dempsey’s Restaurant in New York City, a three-story building opposite Madison Square Garden (the site of several of his epic fights) at Eighth Avenue and 50th Street. For the next 39 years the gregarious Dempsey greeted customers, signed autographs on the numerous giveaways the restaurant provided (postcards, menus, matchbooks) and posing for pictures with anyone who asked.

Michael Corleone in front of Jack Dempsey’s Restaurant

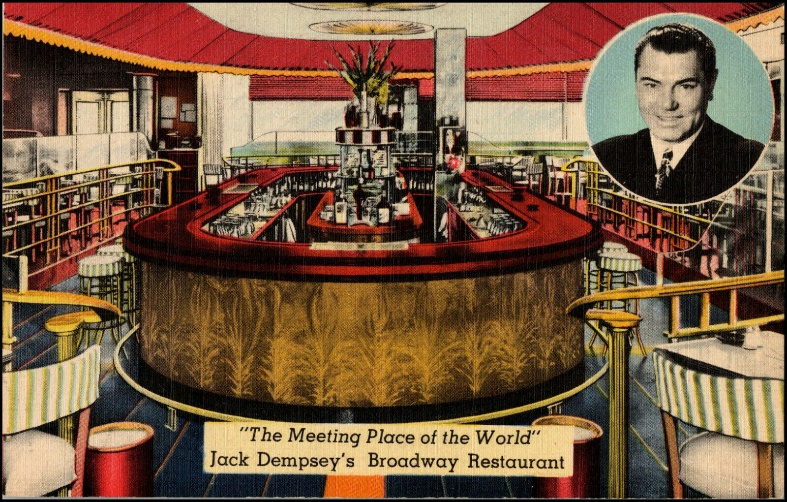

In 1947, a landlord dispute forced Dempsey’s to move the ground floor of the Brill Building (“Tin Pan Alley”), on Broadway between 49th and 50th Streets. There customers could see the champ in the front window, seated at his favorite table. On entering they would be greeted with a “Hiya, Pal” and could dine on shrimp, lobster, steaks, and finish the meal with Jack’s famous cheesecake.

In 1974, Dempsey’s Broadway Restaurant closed, a victim of escalating rent demands. On its closing, he donated the James Montgomery Flagg painting of his fight with Jess Willard to the Smithsonian. Dempsey was 79 and he lived another four years, dying at 83.

Sugar Ray Robinson, like Dempsey, rose to fame as a fighter, eventually holding the welterweight and middleweight championships. Born in 1921, he moved with his mother to New York City’s Harlem neighborhood in 1933 where he took up prize fighting early. By the time he turned professional in 1940, he had won 85 bouts and lost none. Robinson won the welterweight championship in 1946 and held it until 1951, when he became the middleweight champion.

During World War II, Robinson served in the Army and fought exhibition matches with Joe Louis, another of the great prizefighters of the era. He clashed with his superiors when they forbid African-American troops in the audience of these exhibitions. He was honorably discharged in 1944, diagnosed with a “mental deficiency,” likely suffered in a barracks fall.

His prowess was such that the boxing press created a special measure for ring greatness, the “pound-for-pound” ranking, which disregarded the usual weight divisions. Robinson was named the best there ever was in that category. He retired in 1952, beginning a career in show business, singing and tap dancing. After about three years, however, he decided to return to the ring

His comeback in 1955 led him to reclaim the middleweight title. He fought for the next 10 years and holds the record for winning a divisional championship five different times. He retired for good in 1965.

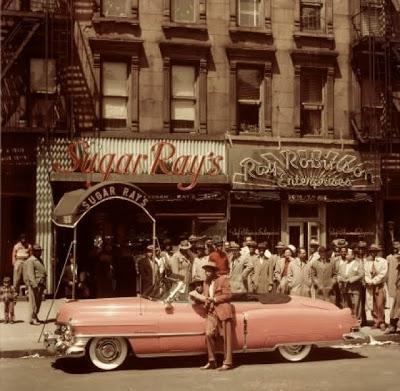

Robinson opened a restaurant, Sugar Ray’s Cafe, in 1946 as an investment. He ultimately owned most of the blockfront along Seventh Avenue between 123rd and 124th Street, where he had Ray Robinson Enterprises (his real estate business), Edna Mae’s Lingerie shop (his wife’s boutique), the Golden Glovers Barber Shop, and a beauty salon.

He was a showman. When he was in town, he’d park his pink Cadillac convertible in front of the restaurant, a car he called it the “Hope Diamond of Harlem.” Unfortunately, his businesses failed, and the restaurant and the other buildings were sold in 1955

Robinson was one of the first black fighters to control the purses of his fights and to manage himself. In his autobiography (Sugar Ray, published in 1964) he said that he’d made $4 million and he and his wife Edna Mae had lived well. But he also wrote that he blew all of it, and as his boxing career faded, so did his businesses. Sugar Ray Robinson died at age 67 in 1989, suffering from the effects of Alzheimer’s disease.