Dr. Donald T. Matter Jr.

The Story of Casey Jones

and the Wreck That Made Him Famous

John Luther Jones was born March 14, 1863. His initial railroad experience was on the M & O Railroad at Columbus, Kentucky. It took him a number of years to gather enough seniority but in March 1888 he joined the Illinois Central as fireman on the Water Valley and Jackson Districts with his seniority board at Water Valley, Mississippi. Opportunities for advancement looked good on the ICRR and Casey’s seniority rights as fireman and later as engineer were on all road and yard jobs from Jackson, Tennessee to Canton, Mississippi. Additionally, there were several blanket passenger runs from Memphis to Canton manned on alternate trips by Water Valley crews. Jones had seniority rights on those runs also. Old records show Jones was promoted to engineer on February 23, 1891, and his name first appears on the register book of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers on March 10, 1891.

As was the lot of newly promoted engineers Jones worked at yard service until he could hold a regular engine. In the summer of 1893 the Chicago World’s Fair was attracting huge crowds to the grounds along the lake on Chicago’s south side. This was ICRR territory and the line was being taxed to provide transportation for the thousands coming to the fair. A call was sent throughout the system for engineers. Jones answered the call and spent the summer doing suburban service in Chicago. It was then that he became acquainted with No. 638. The Illinois Central had their big new freight engine on display at the fair, and at the closing of the fair, the 638 was due to be sent for service in the Jackson District. When Jones learned this, he asked permission to run the engine back to Water Valley. His request was approved, and the No. 638 ran its first 589 miles with Casey Jones at the throttle.

Jones was soon able to find more work on the No. 638. He liked working the Jackson District because his family was there, and Jones spent most of his working days on the 638 until the late 1890s. Over the years Casey had his share of extra passenger runs and he liked the work and the pay, and generally, passenger runs offered much shorter working days, better pay and considerable prestige.

In February 1900 the chief district engineer transferred to a new route thus opening runs No. 1 and No. 4 to a younger engineer. Jones asked for the job, and after ten years as engineer, Jones had a regular “high wheel” job.

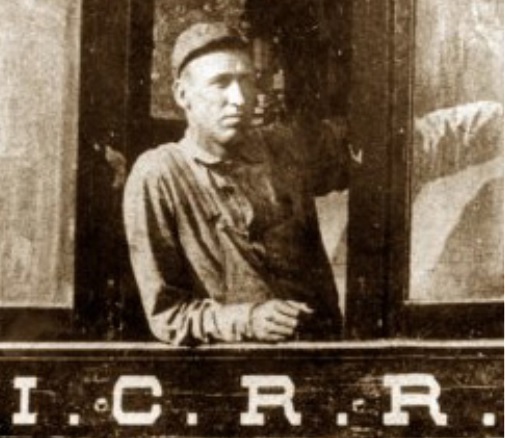

The new job went well. Jones was pleased with the 300 Class passenger engines that were assigned to the run. He missed his co-workers in Jackson, but met a good young fireman named, Sim Webb. Most important was the fact that the job was a challenge to his ability as an engineer. Illinois Central had shortened the running time of its passenger trains between Chicago and New Orleans so that an on-time run was at a pretty good speed.

The schedule allowed about five hours time from Memphis to Canton and about the same time for the return—this was a fairly light day’s work. As passenger demand got heavier and the trains longer, the task became more demanding, but all the officials really demanded of an engineer was that he makes running time. In other words, that he deliver the train to the next division no later on the schedule than he got it. Passenger comfort was not important, and damage suits for being thrown about at high rates of speed were almost unheard of, so dispatchers and other officials looked the other way when too much time was made up. Jones did his best to give them their money’s worth.

On the night of April 29, 1900, Jones was assigned the No. 382 and six cars out of Memphis; fireman Sim Webb with J. C. Turner, conductor. Imagine you are with him on that last run. As the No. 382 moves out of Memphis and through the yard Jones passed the switch at East Junction and told Sim to be ready because it was uphill and fast for several miles. There were slow curves at intervals until he topped Hernando Hill twenty one miles out and then hold on tight for it was down the hill through Love Station and across Coldwater River Bottom as the telegraph poles began to look like a picket fence. One more slow curve south of Coldwater and then the Grenada District racetrack for sixteen miles with only a gentle curve at Senatobia and another at Como.

As Jones passed through Senatobia his thoughts were with Dave Dowling and his fireman Jack Barnett. They had roared through the same way last November and turned over at the south crossing, killing both of them. Funny thing, Jones reflected how the newspaper account headlined the story “Mail Train Delayed by Accident.” At some length it was explained that due to a wreck of the southbound train on Monday morning, the mail was late and several local citizens who were returning from visits to Memphis were quite late getting home. The last sentence briefly stated, “Both the engineer and fireman of the train were killed instantly in the overturning of the giant locomotive.” No names were given!

As Jones passed through Senatobia his thoughts were with Dave Dowling and his fireman Jack Barnett. They had roared through the same way last November and turned over at the south crossing, killing both of them. Funny thing, Jones reflected how the newspaper account headlined the story “Mail Train Delayed by Accident.” At some length it was explained that due to a wreck of the southbound train on Monday morning, the mail was late and several local citizens who were returning from visits to Memphis were quite late getting home. The last sentence briefly stated, “Both the engineer and fireman of the train were killed instantly in the overturning of the giant locomotive.” No names were given!

Jones probably thought a fellow sure deserved to get his name in the paper for that day’s work.

After a quick water stop at Sardis, fifty miles out, Jones noted with satisfaction that he had picked up more time than he hoped. From here to Grenada would be slower, but he could steal a little on the curves and let her ramble across the creek and river bottoms to make up more time. It worked just as he planned and he really let No. 382 go from the top of Hardy Hill to Memphis Junction, one mile from Grenada. Too fast around that curve at Hardy; pity that poor baggage man; he would have to stack it again. If he ever became superintendent, mused Jones, as he stopped for Sim to align the switch at Memphis Junction, he was going to see that this switch was lined for the Grenada district instead of the Water Valley district. He had run through it one morning about two weeks before and his ears were still burning from the tongue-lashing he got from Trainmaster Bill Murphy.

When he stopped for water at the penstock at Grenada, Jones was only about forty minutes late, and a hundred miles out. The light train sure made a difference. He then realized that he had to ease off to keep from going through the curves too fast on top of the hills as well as the bottom. The bosses might call him in about arriving at Grenada too fast. The track was fast from Grenada to Eckridge, some curves up the hill to Sawyer, then a brief stop at Winona. From Winona to Durant he was looking at thirty miles of speedway and no restricted curves. He would see eighty through the creek bottom just south of Magee Siding.

Caution! Red order board at Durant! The northbound passenger No. 2 got orders out of Canton annulling a Durant meet; now they would meet at Goodman. “That Jones boy is showing off again,” George Barnett, engineer on No. 2, would say as he went by Goodman. “He knows they don’t pay a dime more for a fast run than they do a good one.”

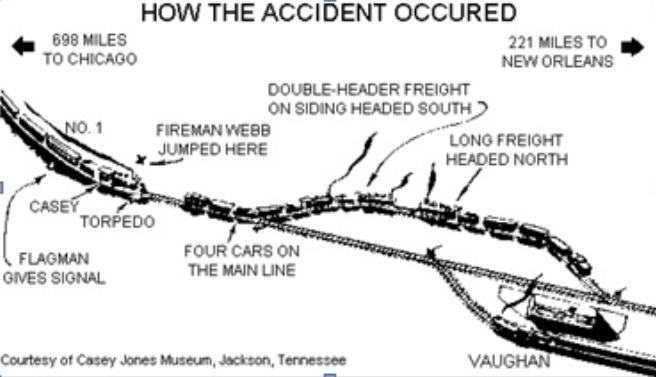

By the time he passed the No. 2 at Goodman, Jones was five minutes late but going to Canton on time would be a simple matter if all went well, but experience told him there was congestion somewhere ahead. As 382 came to Pickens it was almost on time. No trains here in the passing track; they all must be at Vaughan six miles ahead.

Jones was “dead-on.” In Vaughan the No. 72 and No. 83 freights were trying to move off the main line needed for the passenger train when an air hose broke on the fourth car behind the engine on No. 72; No. 72 could not move. No. 83 was blocked by No. 72 and it could not move. Several cars of No. 83’s train were still out on the main line above the north switch. Fireman Kennedy on No. 72 was closest to the broken hose so he rushed back to change it, but the crash came before he could complete the repair.

The No. 382 crashed through the caboose and several cars, lunged crazily to the left and came to rest on the engineer’s side pointing back from whence it came. Jones was mortally wounded by a bolt or piece of splintered lumber that struck him in the throat. A stretcher was brought from the baggage car and crewmen of the other trains carried him a half mile to the depot. While lying on a baggage wagon, Casey died.

The No. 382 crashed through the caboose and several cars, lunged crazily to the left and came to rest on the engineer’s side pointing back from whence it came. Jones was mortally wounded by a bolt or piece of splintered lumber that struck him in the throat. A stretcher was brought from the baggage car and crewmen of the other trains carried him a half mile to the depot. While lying on a baggage wagon, Casey died.

That night they switched out enough cars to make up a train, transferred the passengers and sent them on south. Jones’s body was taken to Canton in the baggage car. Next morning he made the long trip back home to Jackson, Tennessee on passenger No. 26. On the following day a funeral service was held in St. Mary’s Church where he and his wife Janie had married fourteen years before. Burial was in Mt. Calvary’s Cemetery. The newspaper account lists the names of fifteen enginemen from Water Valley who were there to pay their last respects. This too was something of a record; those engineers took-off work and rode 118 miles to Jones’s funeral.

The rail board’s formal investigation concluded that, “Engineer Jones was solely responsible for the accident as consequence of not having properly responded to flag signals.” The implication being that Jones got a sign to pull into a siding but assumed the north switch would have been cleared for him. He made a brake application and was slowing when his fireman saw the caboose and jumped from the coal-tender. The emergency application was not enough, but it slowed the train enough that no passenger or other crew member was seriously injured.

Interesting detail to flesh out a story I’ve been familiar with since childhood. The “mail train delayed” story shows the inverted sense of priorities too common at the time, and even today, with accounts of people demanding their packages from UPS even after being told the delivery was delayed by the truck catching on fire or the driver dying at the wheel.

ok umm idk i am a youtuber

This is a story of the search for punctuality. His skills were great but had their limits. Being on time had a cost too great.

i am sad he die well i know that we will all die one day to see god an see if we are good or bad

Well said.

Yes, we will all die, but you wrote “to see god”. I do agree we will all die and when we are dead, we will not have eyes or a brain to see or think with and therefore not be able to see anything including any gods you may have dreamed up during your life. .

T hey’er all dead now.

My great Grandfather was killed in a train wreck in South Dakota. He worked for another engineer that needed time off and was killed when a trestle had washed out in a flash flood. It was pretty dangerous work back in those days!