Bill Burton

The Civil Rights Movement

and Its Anti-Communist Opponents

The organized fervor that developed into the American civil rights movement that emerged following the U. S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision (1954) can be traced back to at least the American labor movement. Opposition on the other hand is far older.

One theme of that opposition was anti-communism. Before then, proponents of social change were decried as radicals or anarchists. After the post-World War I European revolutions, many people identified elements of the brief successes of communist governments in several countries as a threat. The eventual success of the Bolshevik revolution in Russia was focused on as a worldwide threat and ultimately described as “communist.”

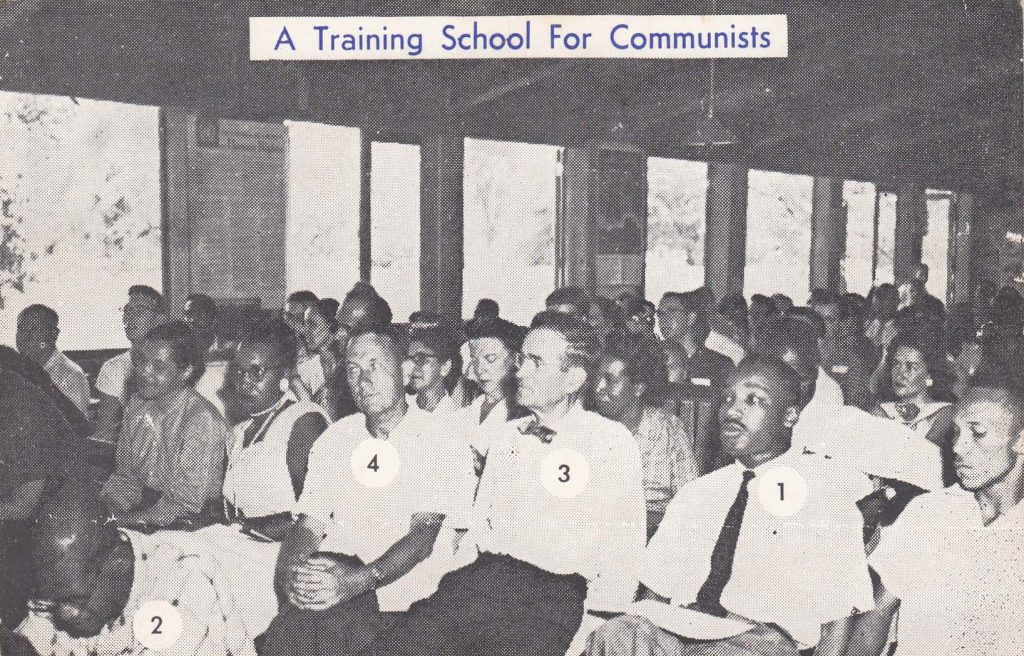

Civil rights activism in the U. S., more often than not was disorganized. The Highlander Folk School, founded in 1932 in New Market, Tennessee, worked to train activists in organizing. In 1957, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., who in 1955 had risen to national prominence as the leader of the Montgomery bus boycott, attended and spoke at its 25th anniversary celebration.

Unbeknownst to those present, and undercover agent of the Georgia Commission on Education was there and photographed the front row of a meeting, capturing King and three other attendees. The photo was circulated against King and was used to brand him as a communist.

Among those using the photograph was the stridently anti-communist John Birch Society, whose publishing arm, American Opinion magazine, published the photo as a postcard.

On the back of the card you see that “these postcards (No. CR2) are available at any American Opinion Library, at 20 cards for $1.00.”

[Another version of this postcard was published by “Councilor” of Shreveport, Louisiana, but titled “Martin Luther King at Communist Training School.” They offered 100 of their cards for $1.]

For what it’s worth, my take on the “were-they or weren’t-they” question is that “communist” has been thrown around so loosely without any proof of communist commitment (in the sense of member or agent of the Communist party) as to be worthless. Dwight Eisenhower was called a communist.

But truthfully, I really wanted to know — where is CR1?

It took a couple of years before I found it on (where else?) eBay. I’d seen this particular card once before but passed it by because it was too expensive. I never looked at the back. When it came up at a price I was willing to pay, I bought it and then looked at the back. Sure enough, there was the American Opinion imprint, in its usual blue, stating “these postcards (No. CR1) are available. . . .”

So who was Joseph Pogány?

First of all, he WASN’T “The Founder of the American Civil Rights Movement” any more than Robert Frost was the first person to mention snow in a poem.

What he WAS is much more interesting. The text on the front of the card is a pretty good summary of his background (allowing for some overwrought adjectives). Pogány was radicalized during World War I and participated as a member of the communist party in the creation the Hungarian Soviet Republic on March 22, 1919.

After the Hungarian Soviet Republic fell in August 1919, Pogány bounced around and eventually arrived in Russia, only to be dispatched to the United States in 1922 to help organize the Hungarian communist party among Hungarian emigres. He quickly mastered English, changed his name to John Pepper, and attended the convention of the American Communist party in Bridgman, Michigan that was raided by Federal and local law enforcement. He barely escaped.

Pepper wrote a strategic document for engaging the party with the struggle of African-Americans, American Negro Problems, in 1928. The text of which can be found at https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/cpusa/1928/nomonth/0000-pepper-negroproblems.pdf. At some point afterward, Pepper returned to Russia and worked in various bureaucratic positions. Eventually he was swept up in Stalin’s Great Purge of 1936-1938, was tried and convicted in 1938 of “participation in a counter-revolutionary organization” in a trial and was summarily executed. Pepper was posthumously rehabilitated by the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR in 1956.

A very interesting article about social movements; I didn’t realize there were John Birch Society postcards.

;

There are three apparent price differences on the card. After it left the original purchaser it was sold for a nickel. Following owner paid 95 cents and a ‘six’ was then penciled in, bumping the price to $6.95 Handwriting styles appear to be from three different hands.

All the cards bear my purchase price notes. When I saw the John Birch Society card I just had to have it, busting my weekly budget. I don’t recall where the second card came from, but the round number suggests a show. The Pogany card was, as I said in the article, an eBay find. I wonder if there are any more Bircher cards — why stop at 2? I once called the American Opinion offices (which aren’t in Massachusetts any more) and talked the librarian there. She had never heard of JBS selling postcards, but then again they came… Read more »

Lynn, I didn’t either! None of these cards have postmarks, so I can’t date them, but perhaps other readers can. Readers did that with the “Mansfield Bar” article, Postcard History‘s first article back in May, 2019. Additionally, the question is, did the JBS publish more than 2?