Terry Bryan

Check This Out

Bank checks are a form of money. Years ago, they could circulate around a local community, being endorsed by each holder. The “maker” of the check would have been known, assumed to have the money on account, and the payees were also known to each other. The redeemed, canceled check acted as a receipt for the payer. Today’s checks only serve for one purchase, payer to payee, cleared through a central facility and forwarded to the proper bank. Writing a paper check is becoming less common, considering all the other payment methods available, but checks have a distinguished history.

Before actual money was invented, deposit receipts from government and private granaries circulated as a form of wealth. Ancient civilizations, such as Egypt, had commerce involving these grain “banks” and the circulating deposit slips, essentially checks when used in this manner. In Genesis, Biblical patriarch Joseph saved Egypt from famine by his inspired banking of crops. Ancient Romans incorporated private banks where checks provided a portable and secure alternative to transporting cash.

In America, colonists were familiar with European banks and checks. Early bank corporations in the Federal Period offered accounts and checks in the late 1700s. Most people did not have cash in banks. Only the wealthiest individuals would use checks.

As commerce, industries and markets developed through the 1800s, more ordinary transactions took place by check. Today’s checks are secured by magnetic inks, anti-alteration printing, and rapid transit through the clearinghouse system.

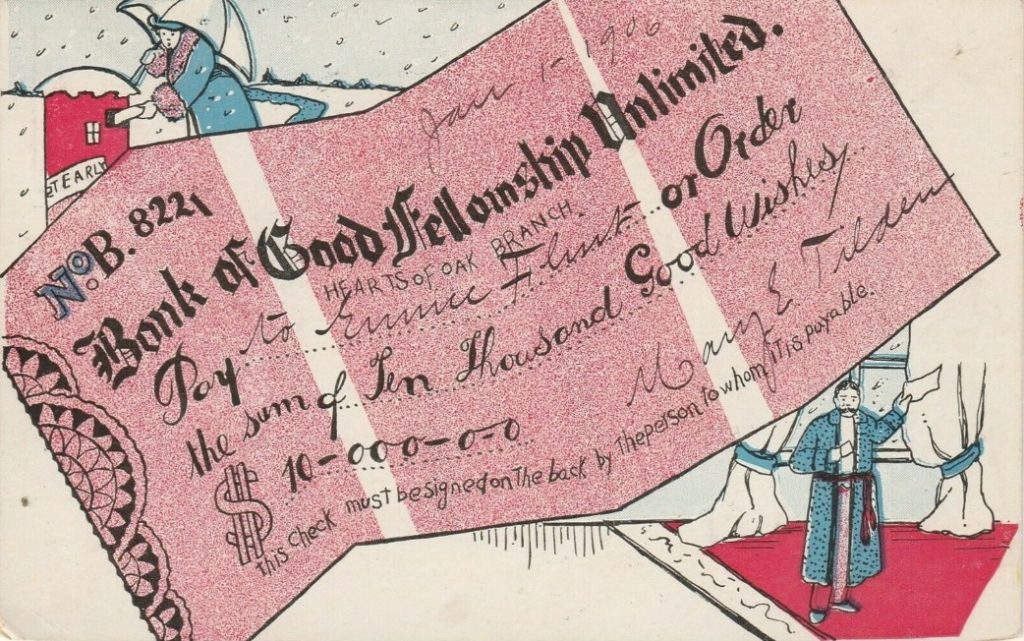

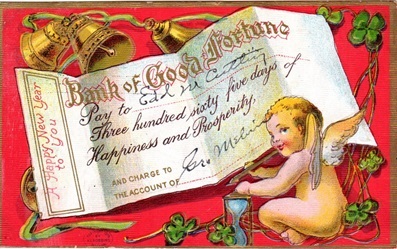

A gift in the form of a check was commonplace. It is the same as cash: one size fits all. Postcard greetings showed informal bank checks drawn on a fanciful Bank of Good Fortune or Prosperity, Good Luck, even Happiness. Most are New Year’s wishes. Father Time often appears. These cards provided a cheery, inexpensive message on occasions when a gift was not called for.