Editor's Staff

The Lost Summer

with Sandra Cobb

To say the least, 2020 has been an unusual year. Who would have thought that a virus that we had never heard about until February would change our lives for what appears to be an undetermined length of time? If you thought like me, the outbreak in China was a concern, but I felt it would be like the Ebola crisis a few years ago. Sure, there were cases, but the doctors knew how to treat it, and soon the crisis was contained. I knew the risks with our connected world, but I had no idea the virus would affect us to the extent it has. After all, we live in 2020 with one of the best medical systems in the world, where the doctors can cure everything. It’s not like 1918 when medical knowledge was limited. Or is it?

My local newspaper recently carried a great article about a family whose son, Bobby Clifton, while serving in the trenches in France, wrote letters to his 16-year-old sister, Annie, at home. In her replies to Bobby, the main topic was the flu the family had and the quarantine at home.

I want to include a paragraph from a letter written by Annie to her brother in October 1918.

All is well here except Papa and he has got the flu. Aunt Nora and Waverly have had it but are well and Johnnie had a slight case of it (sic) Papa is better now though. Nearly everybody has got the flu over here but I think they are getting better now any way (sic) I hope so.

The reporter continued: “Still the teenager likely had no idea how rampant the virus was in her state of Virginia.

On September 13, five weeks before that letter to Bobby, some Virginia newspapers reported the state’s first cases at Camp Lee Army base near Petersburg. Ten days later more than 30 cases were reported at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg. No one was allowed to enter or leave the campus. By early October, Virginia had more than 29,000 cases, more than 350 deaths, and the Associated Press wrote that there was an epidemic in the Tidewater part of Virginia, where cities closed schools, dance and pool halls, and barbershops. Public health announcements ran in newspapers and stated, “do not let anyone cough or sneeze into your face, keep your mouth shut and wash hands frequently.”

Does all this sound familiar? Those cases of the flu started in the United States in April 1918. I remember my mother-in-law telling the story of how everyone in her family except her had the flu. They lived on a farm in eastern North Carolina, and she, only 10- years-old at the time, had to nurse them back to health. No emergency rooms or ventilators or special doctors were available at that time. Eventually even that pandemic was over – but not overnight. It took until the summer of 1919 for the third wave of the flu to subside.

My own experience with quarantine, although not as deadly, had to do with the summer of 1950. I grew up in Wytheville, Virginia and that was the summer of the polio epidemic. 1950 was an extremely hot summer – no air conditioning, no interstate highways. All the traffic going from Bristol to Roanoke on Route 11 had to go right down the main street of our town.

In June, just as the summer was beginning, the first case of polio was reported. It was the son of a semi-professional baseball player who had come to play for the Statesmen, a local team, and had brought his family. One of the next victims was a 9-year-old member of our church. I was ten at the time, and we were all in Sunday School together each week. By the end of the next week he had contracted polio, was sent to Roanoke where all the polio victims had to go. He died within hours. Needless to say, every member of our church who had children was frightened. It had happened so quickly and even members of the family were afraid to go to the funeral for fear of getting sick.

We lived on a small farm on the outskirts of town at the time. From that time on, for the rest of the summer, I never left my home on “the hill.” Mother and Daddy only went into town for necessary items. The news kept getting worse and there were some families who had multiple children come down with the disease. Cars coming through Wytheville rolled up their windows and were even afraid to look around. There were signs on the highway warning travelers of the quarantine and epidemic. Recreation facilities closed and the town was locked down.

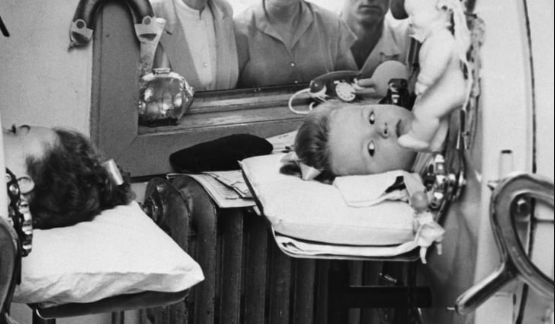

The five local doctors worked tirelessly. There was a constant stream of sirens from ambulances taking the victims to Roanoke – the closest medical center. Some who recovered were paralyzed. Many were placed in iron lungs, and many were crippled for the rest of their lives. There were others who completely recovered. I remember a friend in high school who had been in an iron lung, showed no signs of having the illness. I didn’t know until years later that she had been one of the victims.

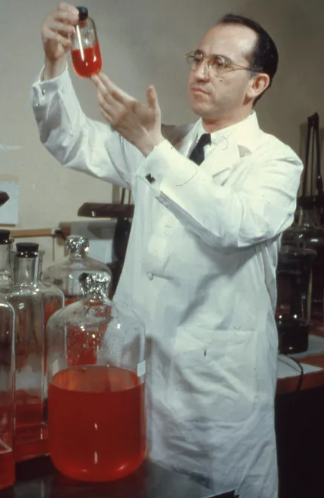

Luckily, the epidemic slowed and then stopped in the fall of 1950, and we were able to survive until the polio vaccine was perfected in 1955. The United States has been polio free since 1979.

As you may guess, few postcards showing aspects of the 1918 flu epidemic are available, but the staff at Postcard History has assembled some cards that show the story of the Lost Summer and the polio epidemic of 1950.

In a strange way, reading about the 1918 flu epidemic and the 1050’s Polio epidemic softens the severity of the current Covid-19 restrictions. The article points out, “this is serious, but it has all happened before.”

When I was a kid in the ’60’s and ’70’s, my dad’s mother didn’t want my siblings to learn to swim because she was afraid they’d get polio from a public pool. (My pediatrician also told me to stay out of the water, but due to the fact I had had tubes inserted in my ears — he figured the vaccine had eliminated the polio threat.)

It is good to review how the earlier flu virus went and also the polio. History helps us realize we can get through it all and to think about the enormaus progress that has been made in fighting things of this sort.