Hy Mariampolski

Human Zoos

Imagine a lovely spring day at the zoo, a fair or an amusement park. Amidst exotic plants and unfamiliar creatures, in a cage or behind a fence sits a family – elders and youngsters included – perhaps an entire clan, in native costumes. They are there for the amusement of passers-by and gawkers alike. They may be cooking and eating unfamiliar foods with strange utensils, performing rituals, or entertaining each other with songs and dances.

The onlookers may be pointing and laughing. Otherwise, they may be disdainful or sneakily aroused by a glimpse of a breast or a buttock. The sightseers may be throwing bits of bread to the captives or sweets for the youngsters. In any case, they fail to see the caged tribalists as people, as members of the same species. They view them as objects to be otherwise disregarded.

This was the reality of human zoos that thrived in Germany, France, and the United States at the turn of the 20th century and in some places lasting long beyond then. Human zoos were a sad legacy of colonialism and a kind of misplaced ethnology. World exploration was bringing us in contact with many kinds of people we had not previously encountered. Our first attempts to classify and understand them put other cultures beneath our own and turned them into commodities and objects of curiosity.

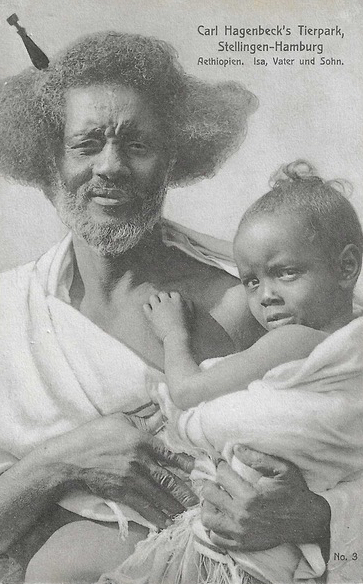

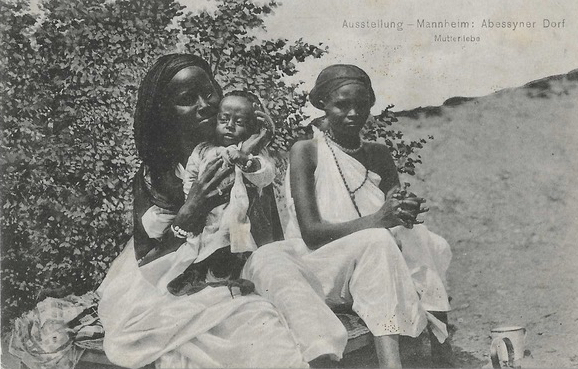

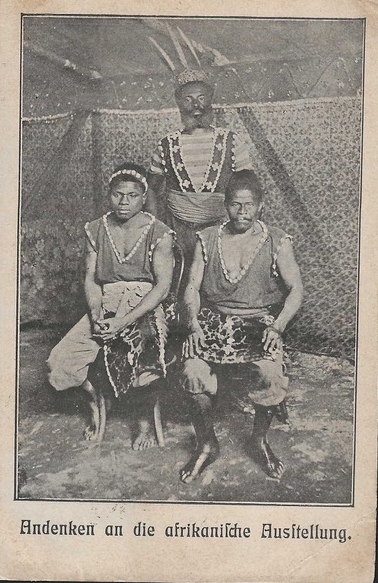

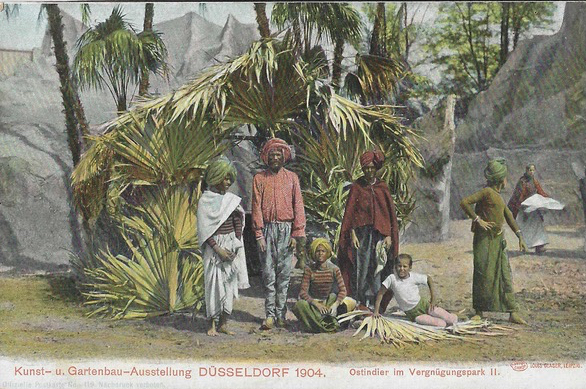

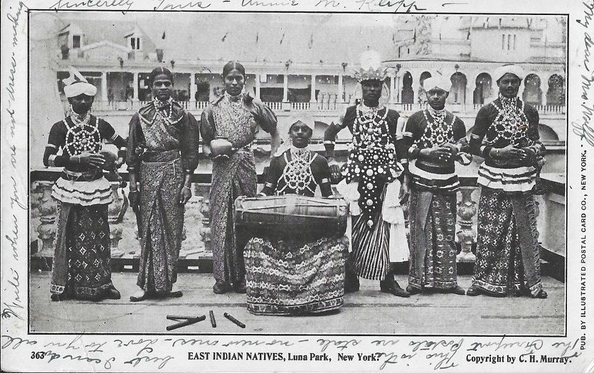

Human zoos were debated and condemned in many quarters. Their reality was captured on numerous postcards of the era.

Carl Hagenbeck was a key figure in the development and growth of Human Zoos in Europe. Following the example of P. T. Barnum, the sensationalistic New York showman who tantalized crowds by exhibiting human “oddities” like Chang and Eng Bunker, the original Siamese twins, Hagenbeck decided to enhance his business of procuring animals for zoos by providing people drawn from the same places in Africa, South Asia and elsewhere, that were then colonies or dependencies of European countries or the United States.

Postcards were typically published to promote industrial or trade fairs, sometimes called “colonial” exhibitions, as well as represent fixed locations such as local parks and zoos. It is no surprise that many postcard images were selected to evoke a sympathetic human response – as in pictures of parents and their children.

Other cards seem to highlight differences, as when people are shown in unfamiliar native garb, standing next to dwellings typical of their homelands or performing what seemed like exotic rituals. The cards below show a family from an “African Exhibition” mailed from Austria to Nebraska, a “Nubian Village” from a 1902 Industrial and Business Exhibition in Dusseldorf, several “East Indians” at a 1904 Art and Horticultural Exhibition in Dusseldorf, and a group of “East Indian Natives” dressed in their finest at Luna Park at Coney Island, New York.

Like most zoo images on postcards, the people are represented at a distance in order to create the illusion that we are seeing them in a “natural” state. A group of men being led in prayer at an improvised “Mosque” at an Ethiopian Village exhibition in Mannheim, Germany, in contrast, shows the actual fences. This bit of reality is jarring in that it reveals the illusion of exoticism that the sponsors are trying to create.

The Bois de Boulogne, a gigantic public park in Western Paris once featured a human zoo without irony called the “Gardens of Acclimatization” that showcased a virtual tribe of Malaysians. Nobody was actually being “acclimatized” here – they were being isolated in a hostile environment.

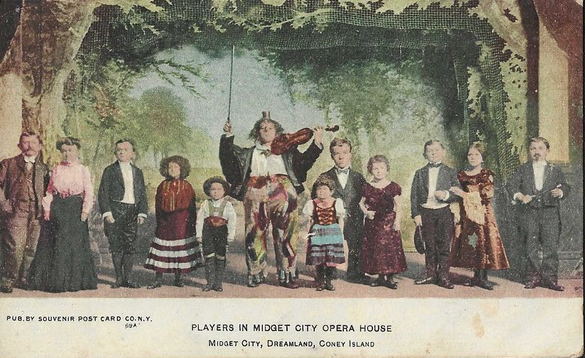

The practice of exhibiting human oddities at circus side shows or “freak shows” reached a new level in the “midget villages” that arose at this time. Coney Island’s Dreamland featured a “Midget City” complete with miniature houses, police and fire departments and a performing opera company.

Questions that occur to many at this point are, “Were these people prevented from escaping? Were they enslaved at a time that slavery had ended?” The answer, obviously, is that there was no place to which they could escape. They were without their own resources, beholden to a recruiter and in unfamiliar territory in an opaque cultural context. Even wearing native costumes was a difficulty for people suddenly cast into an incompatible climate. Many among the natives became sickened and died from exposure.

Truthfully, human zoos failed to offer an authentic and sympathetic view of these denizens of other lands and cultures. The exhibitions were premised on a kind of racism and ethnocentrism that saw Western civilization as supreme and everything else as primitive and not deserving of humane equal treatment.

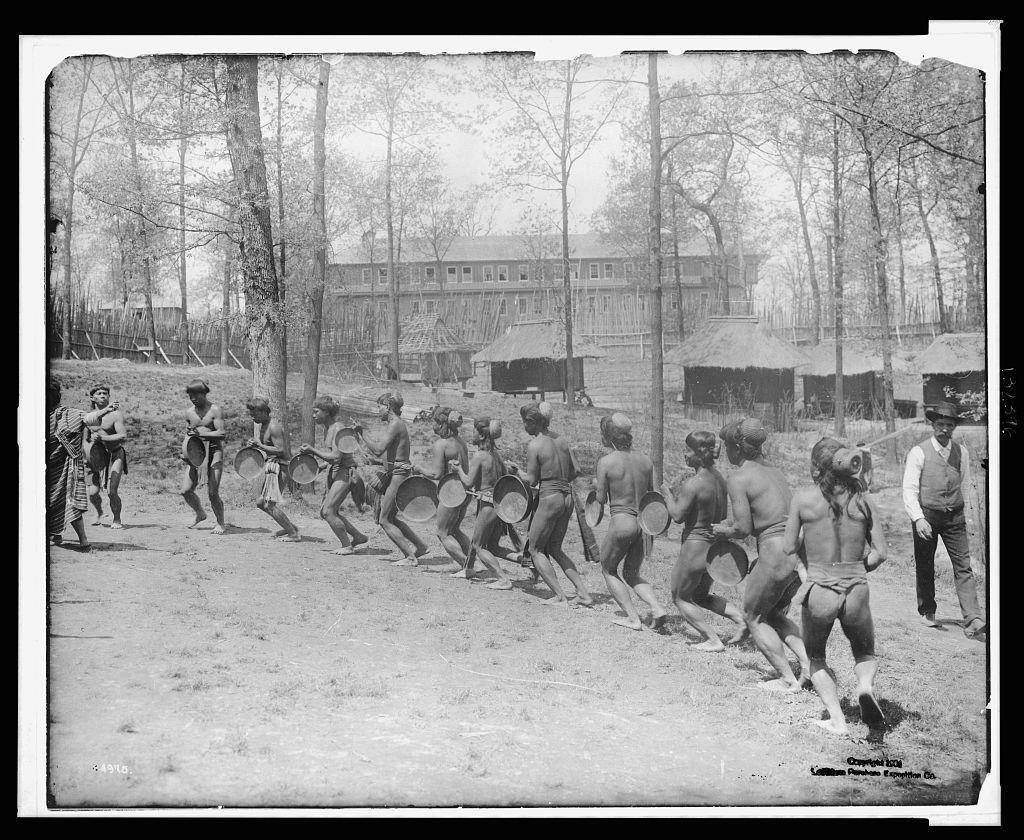

Some of the more egregious examples of inhumanity occurred in the United States at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, also called the World’s Fair in St Louis, and at New York’s Bronx Zoo.

Action in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War had recently brought this nation into the sphere of American colonial dependency. This was fresh in the minds of St. Louis World’s Fair attendees and nothing at the fair aroused their curiosity more than the Filipino natives brought there to introduce Americans to their newest colonial subjects.

Igorot people from the Philippines were exhibited in St. Louis alongside native Alaskans, and Apaches from the Southwest, including even the famous warrior Geronimo. The daily meals of the Igorot included dog meat, to the amusement and horror of spectators, even though in their own culture consuming dog was reserved for special occasions and rituals. Daily performances also showcased dances that for Igorot were normally reserved for special occasions such as weddings and coronations.

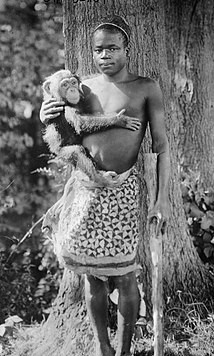

Arriving originally for exhibition in St. Louis was a young African pygmy, Ota Benga from the Congo Free State. By 1906 he ended up at New York’s Bronx Zoo to be exhibited regularly outside the primate house together with chimpanzees and orangutans. Signage disparagingly described the diminutive African as the “missing link.”

The desultory insult was too much for many local African-Americans. In a scathing letter of protest, Brooklyn-based Rev. James H. Gordon wrote, “Our race, we think. Is depressed enough, without exhibiting one of us with the apes.” He added, “We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls.”

The protests grew and shuttered the exhibit. Ota Benga returned to Africa. Unfortunately, he no longer felt at home there nor did he feel like he belonged in America when he came back shortly afterwards. In 1916, Ota Benga committed suicide with a shot to the heart.

In the years since the human zoos fad, we have certainly not solved our problems with racial discrimination. However, looking at these historic postcards shows us that we have come some distance in learning to avoid treating racial, ethnic, and cultural “otherness” as an excuse for objectifying and dehumanizing people different from ourselves.

Wow, I never heard of human zoos, so sad. Although, I did know a little bit about Geronimo

and that sad history. When will humans value one another?

Thank you for the education!

Excellent article. Even though I am a postcard dealer, I did not know about human zoos. I think we have come a long way from the turn of the century although there is still a lot of human prejudice. Thanks for the information.

This is a fascinating article. Thanks.

Another contributor to this magazine wrote an article on The Little People cards that she collects.

Little People Postcards | Postcard History

Years ago I read a book called, Ota Benga, Pygmy in the Zoo, by Phillips Verner Bradford. It was fascinating, and of course, tragic. Ota Benga lived in Lynchburg, VA after he returned from Africa.

It is estimated that 35,000 people were recruited for “human zoos” during the years these attractions were allowed to exist. The Arctic explorer Robert Peary brought six Inuit from Greenland to New York, where they were studied at the American Museum of Natural History. More here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minik_Wallace