Eleanor “Ellie” McCrackin

The Courtship of Miles Standish

It is almost predictable. When the reviews come in, someone will say, ‘… but it’s not true.’ You have seen it happen time-after-time. As soon as any historic novel is published or any movie based on an event is premiered, someone will question the accuracy. Who cares? Novels and movies are entertainment, not history lessons.

The first oral history projects began in the 1960s. Oral history was “invented” as an educational tool to make history come alive for school aged learners, but when all was said and done, the historians had to admit to what a bad idea it was. Early oral history projects were designed to elicit facts, but the sad truth is, the human brain does not remember facts. It remembers experiences, emotions, smells, feelings, tastes, sights and sounds.

The first rule of oral history is . . . never correct the orator. If a memory is corrected it is no longer a memory, it is learned. With that consequence in mind, if you want information on a topic, consult an encyclopedia. If you want memories, ask your grandfather.

When Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote his epic poem, The Courtship of Miles Standish, considerable debate ensued as to the truth of the tale. Longfellow’s terse reply to his critics was, [paraphrased], the characters described by my pen – among them, John Alden and Priscilla Mullins – were ancestors of my mother. They told their story to her; I here am only the scribe, I fairly claim the truth and relate it to you as oral history.

The Courtship of Miles Standish is an extension of the history written in 1620 when the vessel “Mayflower” touched the shore of what would become Massachusetts. There was a fierce war with the Indians happening on the horizon behind Plymouth Rock, the pilgrims are struggling to stay alive in the harsh weather, and there is a love-triangle among three of the Mayflower passengers that is, at its best, adding comic-relief to the everyday life in Pilgrim America.

Longfellow’s first reference to his narrative poem appeared in a diary entry at the end of 1857. His working title was, Priscilla, but by March 1858 he had changed the title. In a critical analysis of the Courtship of Miles Standish, (which is a literary cousin to Longfellow’s Evangeline) a reader will discover nine stanzas with individual titles: three are devoted separately to the three main characters, two reflect the philosophical principles of love and friendship, three align the history of the colony and the last retells the events on the day John and Priscilla marry:

I. Miles Standish

II. Love and Friendship

III. The Lover’s Errand

IV. John Alden

V. The Sailing of the Mayflower

VI. Priscilla

VII. The March of Miles Standish

VIII. The Spinning-Wheel

IX. The Wedding-Day

The account of the march of Miles Standish is the seventh stanza of the epic, it is one of the three historic accounts. The complete stanza is reprinted below, complete with its antique spellings and dropped syllables. If you have never read it before, I hope you enjoy this opportunity and I hope again that it may spur you on to read the other eights stanzas (all of which are easily found on the Maine Historical Society’s website and others.

Miles Standish was the military captain at Plymouth Colony. In the famous historical print seen on this postcard, Standish with his men follow their Indian guide

“to quell the revolt of the savages.”

The March of Miles Standish

Meanwhile the stalwart Miles Standish was marching steadily northward,

Winding through forest and swamp, and along the trend of the sea-shore,

All day long, with hardly a halt, the fire of his anger

Burning and crackling within, and the sulphurous odor of powder

Seeming more sweet to his nostrils than all the scents of the forest.

Silent and moody he went, and much he revolved his discomfort;

He who was used to success, and to easy victories always,

Thus to be flouted, rejected, and laughed to scorn by a maiden,

Thus to be mocked and betrayed by the friend whom most he had trusted!

Ah! ‘t was too much to be borne, and he fretted and chafed in his armor!

“I alone am to blame,” he muttered, “for mine was the folly.

What has a rough old soldier, grown grim and gray in the harness,

Used to the camp and its ways, to do with the wooing of maidens?

‘T was but a dream,–let it pass,–let it vanish like so many others!

What I thought was a flower, is only a weed, and is worthless;

Out of my heart will I pluck it, and throw it away, and henceforward

Be but a fighter of battles, a lover and wooer of dangers!”

Thus he revolved in his mind his sorry defeat and discomfort,

While he was marching by day or lying at night in the forest,

Looking up at the trees, and the constellations beyond them.

After a three days’ march he came to an Indian encampment

Pitched on the edge of a meadow, between the sea and the forest;

Women at work by the tents, and the warriors, horrid with war-paint,

Seated about a fire, and smoking and talking together;

Who, when they saw from afar the sudden approach of the white men,

Saw the flash of the sun on breastplate and sabre and musket,

Straightway leaped to their feet, and two, from among them advancing,

Came to parley with Standish, and offer him furs as a present;

Friendship was in their looks, but in their hearts there was hatred.

Braves of the tribe were these, and brothers gigantic in stature,

Huge as Goliath of Gath, or the terrible Og, king of Bashan;

One was Pecksuot named, and the other was called Wattawamat.

Round their necks were suspended their knives in scabbards of wampum,

Two-edged, trenchant knives, with points as sharp as a needle.

Other arms had they none, for they were cunning and crafty.

“Welcome, English!” they said,–these words they had learned from the traders

Touching at times on the coast, to barter and chaffer for peltries.

Then in their native tongue they began to parley with Standish,

Through his guide and interpreter Hobomok, friend of the white man,

Begging for blankets and knives, but mostly for muskets and powder,

Kept by the white man, they said, concealed, with the plague, in his cellars,

Ready to be let loose, and destroy his brother the red man!

But when Standish refused, and said he would give them the Bible,

Suddenly changing their tone, they began to boast and to bluster.

Then Wattawamat advanced with a stride in front of the other,

And, with a lofty demeanor, thus vauntingly spake to the Captain:

“Now Wattawamat can see, by the fiery eyes of the Captain,

Angry is he in his heart; but the heart of the brave Wattawamat

Is not afraid at the sight. He was not born of a woman,

But on a mountain, at night, from an oak-tree riven by lightning,

Forth he sprang at a bound, with all his weapons about him,

Shouting, ‘Who is there here to fight with the brave Wattawamat?'”

Then he unsheathed his knife, and, whetting the blade on his left hand,

Held it aloft and displayed a woman’s face on the handle,

Saying, with bitter expression and look of sinister meaning:

“I have another at home, with the face of a man on the handle;

By and by they shall marry; and there will be plenty of children!”

Then stood Pecksuot forth, self-vaunting, insulting Miles Standish:

While with his fingers he petted the knife that hung at his bosom,

Drawing it half from its sheath, and plunging it back, as he muttered,

“By and by it shall see; it shall eat; ah, ha! but shall speak not!

This is the mighty Captain the white men have sent to destroy us!

He is a little man; let him go and work with the women!”

Meanwhile Standish had noted the faces and figures of Indians

Peeping and creeping about from bush to tree in the forest,

Feigning to look for game, with arrows set on their bow-strings,

Drawing about him still closer and closer the net of their ambush.

But undaunted he stood, and dissembled and treated them smoothly;

So the old chronicles say, that were writ in the days of the fathers.

But when he heard their defiance, the boast, the taunt, and the insult,

All the hot blood of his race, of Sir Hugh and of Thurston de Standish,

Boiled and beat in his heart, and swelled in the veins of his temples.

Headlong he leaped on the boaster, and, snatching his knife from its scabbard,

Plunged it into his heart, and, reeling backward, the savage

Fell with his face to the sky, and a fiendlike fierceness upon it.

Straight there arose from the forest the awful sound of the war-whoop,

And, like a flurry of snow on the whistling wind of December,

Swift and sudden and keen came a flight of feathery arrows,

Then came a cloud of smoke, and out of the cloud came the lightning,

Out of the lightning, and death unseen ran before it.

Frightened the savages fled for shelter in swamp and in thicket,

Hotly pursued and beset; but their sachem, the brave Wattawamat,

Fled not; he was dead. Unswerving and swift had a bullet

Passed through his brain, and he fell with both hands clutching the greensward,

Seeming in death to hold back from his foe the land of his fathers.

There on the flowers of the meadow the warriors lay, and above them,

Silent, with folded arms, stood Hobomok, friend of the white man.

Smiling at length he exclaimed to the stalwart Captain of Plymouth:

“Pecksuot bragged very loud, of his courage, his strength, and his stature,—

Mocked the great Captain, and called him a little man; but I see now

Big enough have you been to lay him speechless before you!”

Thus the first battle was fought and won by the stalwart Miles Standish.

When the tidings thereof were brought to the village of Plymouth,

And as a trophy of war the head of the brave Wattawamat

Scowled from the roof of the fort, which at once was a church and a fortress,

All who beheld it rejoiced, and praised the Lord, and took courage.

Only Priscilla averted her face from this spectre of terror,

Thanking God in her heart that she had not married Miles Standish;

Shrinking, fearing almost, lest, coming home from his battles,

He should lay claim to her hand, as the prize and reward of his valor.

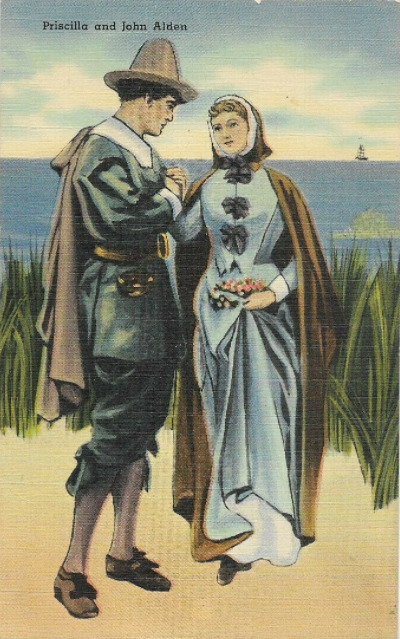

Artistic rendering of the Aldens as seen on a Tichnor linen postcard, circa 193o.

Likely from an oil painting, ownership and location unknown.

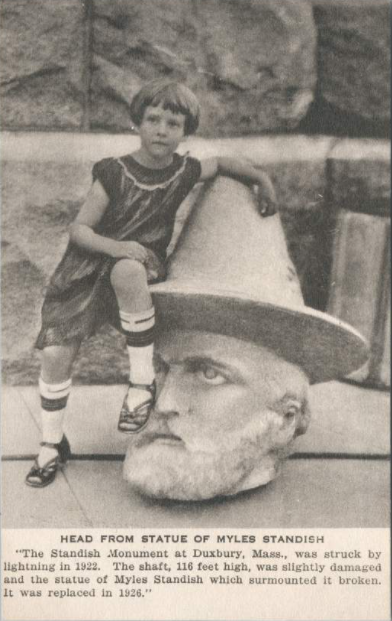

A monument to Myles Standish was struck by lightning in 1922 (replaced in 1926).

This Albertype postcard shows a devoted visitor in the interim.

When John and Priscilla left the Plymouth Colony they took

residence in Duxbury, Massachusetts, just a few miles north.

The grave of Myles Standish is in the oldest maintained cemetery in the United States. It is the final resting place for many pilgrims who arrived on the Mayflower.

The postcard collection from which these cards are borrowed form part of a family album. The family surname is Longfellow and there is lineage from the poet. In this case it is not oral history, but fact. Any questions?

Although I was familiar with the story of the Alden-Mullins-Standish triangle, I never read any part of Longfellow’s poem about it until just now.