Marie Hahn

Quilts from America’s Corners

Even when dispirited by the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) and those it employs, long distance travelers in the 21st century have a much easier experience when compared to the effort, expense, and time it took in 1811. Egad, you ask, why 1811? I’ll tell you later.

The development of transportation in 1811 had not developed beyond the basics. Let’s see, there were feet, boats, and horses, therefore as our pioneer fathers and mothers reached their domestic destinations from wherever they started, we can assume they got there on their feet, aboard a boat or either astride or behind a horse.

Why 1811? The answer is Henry Clay. Forget who he was? No need to Google; I’ll tell you.

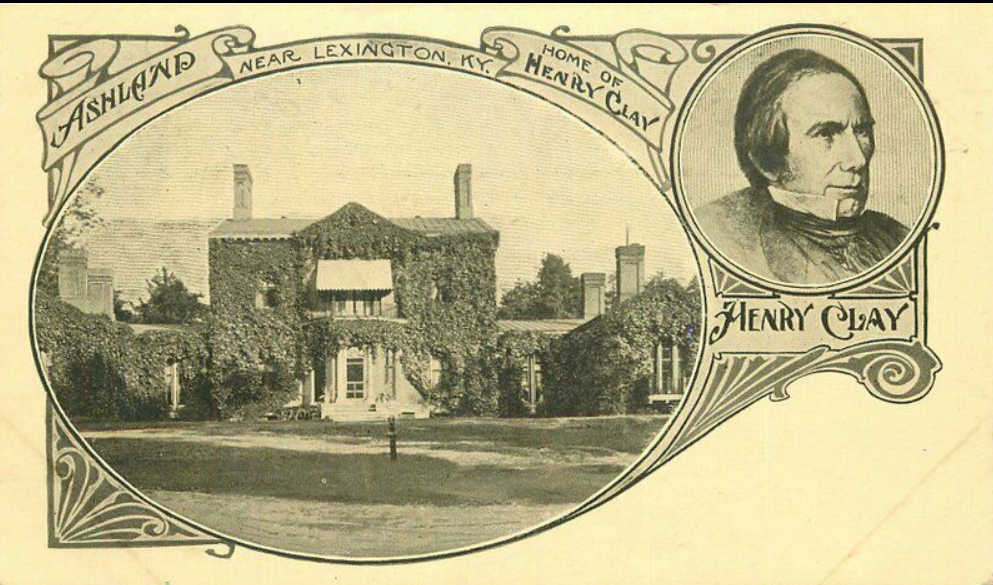

Henry Clay and his Ashland estate, near Lexington, Kentucky, circa 1809

Henry Clay was born on April 12, 1777, on the family farm in Hanover County, Virginia, in a frame house that the historians call a story-and-a-half. That means the house had an attic that doubled as bedrooms for Henry and his fifteen siblings. That may explain why he wanted to move to Kentucky.

After a reasonable education in a law office, Henry decided at age 20 to relocate to Lexington and practice law. I’ll skip the details; however here is a thumb-size bio.

Henry managed to open a law office in Lexington in 1797, he married Lucretia Hart in 1799. Within the first decade of their life together the Clays set goals which included the acquisition of a substantial residence. In 1804 their first step toward success was the purchase of a farm on the edge of town. The plans for their home were drawn immediately and by 1809 the main part of their home was complete.

Henry campaigned for a congressional seat and was elected to his first Congressional term in 1811. In addition, between 1800 and 1821 the Clays had eleven children.

Ashland, circa 1844

In 1811 someone must have asked, “Mr. Clay, are you sure you want to be a politician? Remember, after you’re elected, you must travel to Washington, DC, and the road to Washington takes you across the mountains of eastern Kentucky, and you must cross two major rivers – the Ohio and Kanawha. Then you must go through the entire state of Virginia (most of which became West Virginia in 1863) to Williamsport, Maryland, where you will board a river barge heading down the Potomac River to the nation’s capital. That will be 532 miles. It will take you nearly three weeks. Along the way you will need to worry about the safety of your family and whoever is carrying the hundreds of pounds of belongings you, your wife and children will need.”

Children create added concerns for the traveler and often at unexpected times. After six years of successful trips to Washington, in 1817, a severe illness overwhelmed Laura, the Clay’s then youngest daughter. Laura’s illness caused the family to remain in Ohio for over a month and when it seemed she would recover, Henry went on to Washington alone – he was in the midst of his second term as Speaker of the House of Representatives. But all was not well; on the morning after his arrival Henry read his daughter’s obituary in a Washington newspaper.

Today we have the advantage of hindsight, and we realize the true crux of the problem. There were no Sheraton Hotels, nor McDonald’s Restaurants, not even a Walmart. In those days if luck provided you with a place to sleep you still had to unpack everything you were carrying. Now dear reader, let’s think of just one item that had to be part of their luggage – quilts. Think about how heavy quilts are!

These postcards from the interior of Clay’s Lexington home show two bedrooms. The first being a master room that was the largest room on the second floor of the home. On the bed you see a Grandmother’s Garden quilt. The design was among the most popular of the early years of American’s mid-western expansion. The acceptance of a Grandmother’s Flower Garden (assembled in alternating rows and columns of honeycombs and hexagons), remained popular until the 1930s. And, we all know of the recent trend in quilting to return to those old designs.

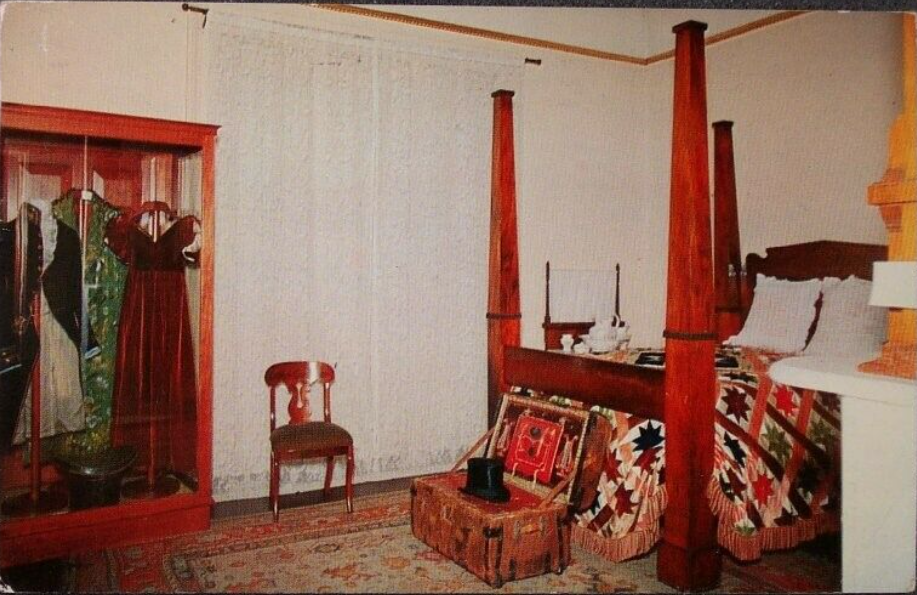

The postcard (right) of another bedroom in Clay’s home shows a four-poster bed covered with an eight-point star block quilt known as a Lemoyne Star. I learned in a phone conversation with Mr. Eric Brooks, the exhibits curator at Ashland (the Clay estate) that this quilt is an exact replica of one made especially for Henry Clay by a guild of quilters in Philadelphia. The 1844 original is in protective storage at the estate.

The Lemoyne Star quilt was often assembled by repositioning diamond shapes cut from squares. (Honest, it’s easy once you know how!) The Lemoyne design also enjoyed great popularity in the early years of frontier living. Quilt makers and amateurs alike often reserved the Lemoyne for there “best” quilts.

This story ends here. The Clays are moldering in their graves and some of their quilts have crumbled to dust. Remember though that old Henry, who while he served our nation for many years as a Congressman, Senator, and Secretary of State, traveled to and from Washington carrying his own quilts.

[Editor’s note. This article was one in a series and appeared in the newsletter of the Garden Patch Quilt Guild in April 2012. The article reminds the club members that their craft often appears on postcards.]

Beautiful quilts! Why would travellers need to bring their own quilts? Wouldn’t the places they stayed have provided them, along with the bed?

As a Folk Art historian, I enjoyed this article. Quilts are certainly an American treasure. And its worth comes in many forms. Here is a bit of history that I did not know. Thank you for the article.

Clay is famous for saying “I would rather be right than President” when told during a campaign that his abolitionist position would cost him the election. It is interesting to speculate on whether the man known as the Great Compromiser could help solve the gridlock in Washington today.