Bill Burton

The Steamer President Warfield

and

the Exodus 1947

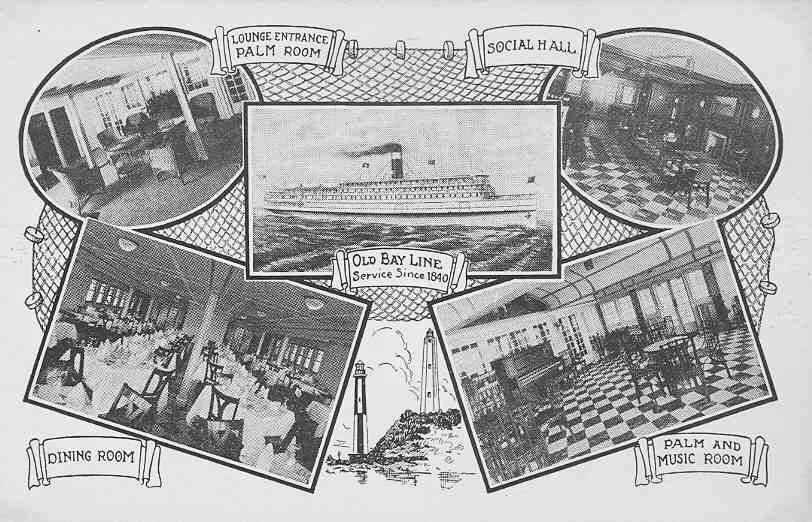

Born from the competition for delivering freight and passengers between the City of Baltimore and points along the Virginia side of the Chesapeake Bay (Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Old Port Comfort), the Baltimore Steam Packet Company was created in 1840 from the melding of its assets and those of the bankrupt Maryland & Virginia Steam Boat Company.

Railroads were in the distant future and overland travel was daunting, so steam ships (called “packet ships” because they carried both passengers and freight) provided efficiency and certainty.

The Union blockade of the Virginia side of the Chesapeake during the Civil War crippled packet ships, but the Baltimore company survived. It never changed its name but became known as “The Old Bay Line” during an 1865-67 fare war with the New York-based Leary Line (the Baltimore company distinguished itself from the upstart by referring to itself as “the old established Bay Line”).

Leary withdrew in 1867 and the Old Bay Line emerged as the dominant packet service in the bay. Well into the early twentieth century they launched new ships that boasted steel hulls, propellor drives that replaced paddle wheels, luxurious to the point of sumptuous passenger accommodations and electricity arrived.

S. Davies Warfield, a railroad executive, became president of the company in 1918. His death in 1927 seems to have traumatized the company, as never before had one of its ships been named for a person. The SS President Warfield went into regular service on the Chesapeake in 1928 and was still serving when, in 1942, it and three other Old Bay Line ships were requisitioned by the U. S. government’s War Shipping Administration and turned over to the British for troop carrier duty.

The Warfield returned to active service in the Chesapeake in 1945 but it soon became clear that the cost of reconditioning the ship would be too high, and in November 1946 the company sold it to the Potomac Shipwrecking Company of Washington, D.C., an agent of the Jewish political group Haganah.

On February 1947, the Mossas Le’aliyah Bet, a branch of the Haganah, sailed the Warfield to France. The ship’s passenger capacity was less than 700, but it became the largest ship in the 64-ship fleet that the Aliyah Bet assembled.

The fleet’s purpose was to help Holocaust survivors leave various displaced person camps throughout Europe and reach Palestine. At the time, the British in their administrative mandate over Palestine, forbad new Jewish immigration, in part due to their complicated relationships with various surrounding Arab countries. There was already substantial illegal immigration to Palestine, but it in no way met the need.

The Warfield, like all the ships in the fleet, was renamed, in its case, Exodus 1947.

The crew was made up of about 35 Zionist volunteers. Prior to setting sail from the U.S., much work had been done to accommodate the passengers, including two weeks’ worth of supplies, various medical facilities, and defensive positions on the various decks, the engine room, and wheelhouse.

Exodus 1947 reached Sete, France, (a beach community on the Gulf of Lion) near Montpellier, loaded with 4,515 refugees. It then departed on July 11, ostensibly for Istanbul. Aliyah Bet knew the British were aware that the real destination was Palestine. British surveillance was immediate, both by air and by navy vessels.

During the voyage, passengers were trained in repelling an interception attempt. The plan was to beach the ship and for the passengers to flee inland, but the British boarded the ship on July 18 and thwarted that plan. Resistance was stubborn and one man in the wheelhouse, Bill Bernstein, was clubbed to death. Two other passengers were shot to death and two British sailors were wounded.

Typically, illegal immigrants were sent to the island of Cyprus, a British possession, but the high profile that Exodus 1947 had developed during the voyage led the British government to change that policy.

The new policy was a strong statement to both the Jewish community and to the European countries from which the refugees came. Simply it was that anyone they permitted to try for Palestine would be sent back to them. The High Commissioner for Palestine made it clear that “Not only should it clearly establish the principle of refoulement [that intercepted refugees would be sent back to their countries of origin] as applies to a complete shipload of immigrants, but it will be most discouraging to the organisers of this traffic if the immigrants … end up by returning whence they came.”

The passengers were re-loaded onto British ships and arrived in France on August 2. The French stated that they would allow only passengers who were willing to disembark to do so. Haganah agents urged to passengers to stay on board and they did so. They went on a 24-day hunger strike when the realization came to them that they were going to be sent to Germany, possibly to the old concentration camps.

The press was all over the situation. Finally the British decided to move the refugees to camps in the British-occupied zone of Germany. The ships that carried them arrived but the refugees refused to leave. A detachment of British soldiers was sent in to remove them and a series of major confrontations ensued. In the end 68 refugees were injured compared to only three soldiers.

That soft British spin was contradicted by Dr. Noah Barou, an official observer from the World Jewish Congress, who reported that the soldiers used their batons in the stomachs of the resisting refugees, so that no obvious wounds were visible.

The British camps were not suitable for winter use and the refugees were transferred to more suitable camps, which happened to be close to the American zone. Over the winter many of the refugees were smuggled out of the camps by an underground group called the “Bricha.” By Spring only about 1,800 refugees were left in the British camps.

The refugees made various attempts to reach Palestine, most of which failed, with the result that they were sent to Cyprus. It was only when the British recognized the existence of Israel in 1949 that these refugees were transferred there.

The Irgun, a militant Zionist paramilitary group, retaliated for the treatment of the passengers of Exodus 1947 on September 29, 1947, by detonating a bomb at the British police headquarters in Haifa. The building was so badly damaged and the loss of life so great that the building was demolished.

With the establishment of the State of Israel on May 14, 1948, and the subsequent war, Exodus 1947 was forgotten. Along with many other ships from the Aliyah Bet fleet, it was moored at a breakwater in the port of Haifa. In 1952 the ship caught fire and the hulk was towed out of the way. After several other attempts were made to resurrect the hulk, it was buried in the modern container ship quay in Haifa harbor.

A documentary, Exodus 1947, The Ship that Launched a Nation based on a 1998 book by Ruth Gruber, can be seen on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=II9mU5ERYak.

Seafaring stories on postcards are irresistible and I enjoyed learning the history of the Exodus 1947. Thank you for a very interesting history lesson!

This article reminded me of the saga of the MS St. Louis, whose 937 passengers (mostly Jewish refugees) were not allowed to enter the U.S. in 1939.