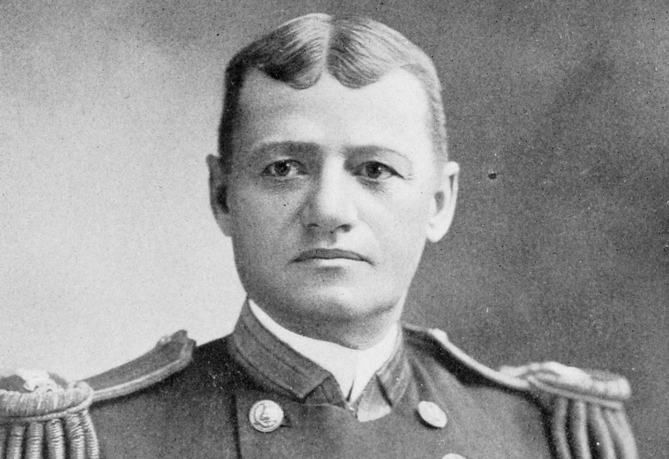

Timothy Van Staden

Robley Dunglison Evans

“Our Bob”

Shakespeare wrote Twelfth Night or “What You Will,” a romantic comedy about 1601. The term Twelfth Night is frequently associated with Christmas time and it may be that Shakespeare meant this play to be part of the entertainment prepared for the 1601 or 1602 holiday seasons. Two of the main characters are a set of twins, Sebastian and Viola who are separated in a shipwreck.

The production is in five acts. I quote the very best summary ever, “Viola thinks her brother is dead. He thinks that she is dead. Everyone thinks that she is her brother. Everyone thinks that her brother is her. Shenanigans ensue.”

The production is also inane and slapstick, since Viola, after being separated from her twin brother, dresses as a man and takes employment with Duke Orsino with whom she falls in love. Orsino loves the Countess Olivia. Orsino sends Viola to court her for him, but Olivia falls for Viola instead. When Sebastian arrives, his presence confuses everyone and marries Olivia. Viola then reveals she is a girl and marries Orsino.

In spite of the nonsensical plot, in Twelfth Night Shakespeare creates some of the most memorable lines in classic literature, i.e., in Act 1, Scene 1 there is, “If music be the food of love, play on.”

Then in Act 2, Scene 5 Malvolio (Lady Olivia’s steward) tells Olivia, “Some are born great, some achieve greatness and some have greatness thrust upon them.”

Yes, “Some are born great” is a line from Shakespeare, NOT President Teddy Roosevelt.

* * *

So, 1601 wasn’t exactly yesterday, but nearly 250 years later, in the summer of 1846 Robley Dunglison Evans was born in Floyd County, in south-western Virginia. “Our Bob” as he was affectionately called grew up to be a man that exemplified every one of the criteria Shakespeare associated with greatness and the achievement of greatness.

Robley D. Evans was enrolled in the United States Naval Academy at age 14 after being offered a nomination by Utah Senator W. H. Hooper the year before. Evans needed to establish Utah residency to take advantage of the nomination, and then entered Annapolis in 1860. He was put on active duty in September 1863 and graduated with the class of 1864.

In January 1865 near the end of the American Civil War, Evans led a party of Marines in the second battle for Fort Fisher (North Carolina) where he sustained his first combat wound. And, his second, third, and fourth wounds. This was when his greatness really started. In the end, Evans was sent to a hospital at Norfolk. His wounds were so severe that a surgeon approached him with a suggestion to amputate his leg. At that point Evans pulled a pistol from under his pillow and said he would shoot at the first sign of a surgeon’s saw. He was left-alone to die of his injuries.

“Our Bob” didn’t die of his wounds. After the Civil War, because of his injuries, he was medically retired from the navy, but after several appeals to Congress for reinstatement, he was again placed on active duty in command of the U.S.S. Yorktown that figured prominently in the Chilean incident of January 1891.

The conflict in Chile lasted just over a year with a resolution that went unprotracted because of Evans. The sobriquet “Our Bob” faded away and he became “Fighting Bob Evans.” This was the only of his nicknames that he questioned, he always thought it to be silly, since it was because of him that there was no fight with Chileans.

When the Spanish-American War started, Captain Evans was ordered to the U.S. S. Iowa – the Navy’s newest and largest battleship. Iowa served valiantly in the war. In many of its encounters the Iowa suffered no losses to the crew; a fact that had special meaning to Evans since serving under him aboard the Iowa was his son, a naval cadet. (Captain Evans’s son, Franck Taylor Evans, would later become a Captain in the U. S. Navy, who won awards of valor in France, Greece, Japan, Spain, and Italy.)

One particular event that appeared in Admiral Evans’s obituary in 1912 recounts a situation within the War Department when the Secretary of War called on the Admiral for a status report concerning coastal defenses around Havana and what probable capacity Cuba may have to withstand a siege. Evans replied, “We can lick ‘em easily. Give the permission at once to shell Havana, and I promise you that there will be no language, except Spanish, spoken in hell for the next forty-eight hours.”

At the end of the Spanish-American war, as he always did, Captain Evans included complimentary statements in his reports about his “admiration for his magnificent crew.”

Because of Evans’s exemplary service and now holding the rank of Rear Admiral, Robley D. Evans received orders from his Commander-in-Chief, President Theodore Roosevelt to command the expedition that came to be known as the “Great White Fleet.” A squadron of sixteen battleships and several ancillary vessels, on the first leg of its long world cruise left Hampton Roads, Virginia, on December 16, 1907. After cruising around South America, passing through the Straits of Magellan, and visiting many countries along the way, the fleet arrived in San Francisco Bay on May 6, 1908. That may have been the only date in Evans’s career that he was happy to be ashore. He suffered a great deal in those last few duty months. He spent most of those last four months on sick-call, in bed in pain.

Evans’s Civil War injuries left him with a limp and severe pain for the rest of his life. Because of this limp, Evans was affectionately dubbed “Gimpy” by the crews of the ships under his command. Evans knew his sailors called him Gimpy but wore the name as a badge of honor especially during his command duty with the Great White Fleet.

In San Francisco, due to his health, Evans relinquished his command to Rear Admiral Charles Mitchell Thomas. The “Great White Fleet” then continued and made stops in ports around the globe. Mission Accomplished! The United States was indeed a world power. They returned to Hampton Roads on February 22, 1909.

When Admiral Evans surrendered his command in San Francisco, he effectively retired. He had reached the mandatory retirement age of 62 and had served his country for 47 years, 10 months, 28 days.

He lived to see the return of his “Fleet” in 1909.

He died January 3, 1912.

Thanks very much for a great report on Admiral Evans! As a Navy postcard enthusiast I learned much more about his life and service from your work

Since Utah was still a territory in 1860 (it finally gained statehood in 1896), Hooper was officially a non-voting delegate to the House of Representatives, not a senator, when he nominated Evans to the Naval Academy.

For a non-navy enthusiast I found this article – well – ho hum.