George Miller

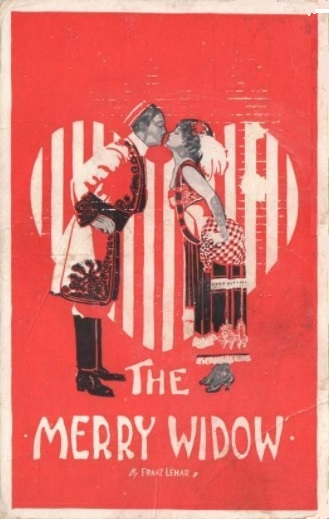

The Merry Widow

A Lady Who Captured the World’s Heart

The Merry Widow is a three-act opera. The plot varies slightly from the original German version to the English translation as it was first produced in the United States. In addition, the English translators changed the name of the imaginary country (originally Pontevedro) and the characters (Sonia, for example, was Hanna). This summary follows the operetta as it was known to American audiences in 1907.

Act One. It is 1905 in the palace of the Marsovian Embassy in Paris. A party is in progress, and Baron Popoff is toasting the birthday of the ruler of Marsovia. Meanwhile, Natalie, the Baron’s wife, is flirting with Jolidon, a Frenchman. The baron, oblivious to his wife’s indiscretions, is worried only about the fate of Sonia, the “merry widow,” one of Marsovia’s wealthy citizens, who has come to Paris and is, understandably, besieged by fortune hunters. Should she marry a foreigner, the baron ponders, the loss of her wealth will signal financial ruin for their country. A possible solution to the problem appears when Prince Danilo, the Marsovian Minister of Finance, enters. The prince and the widow were in love once, but the prince is now reluctant. He is too proud to marry her for her fortune, even to save his country. Dancers enter and the next dance is a “ladies’ choice.” When the widow asks the prince to waltz with her, he at first declines and then eventually asks her. The curtain falls.

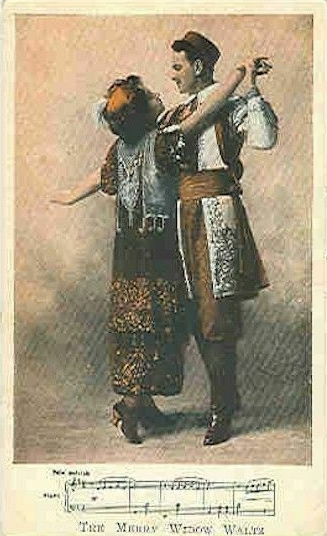

When the curtain rises on Act II, the action has shifted to a garden party at the widow’s house near Paris. Sonia sings the songs of her Marsovian homeland to her assembled guests. Left alone with the prince, she sings a song about a “silly, silly horseman” who is unaware or unable to act on a lady’s love for him, an obvious reference to themselves. Danilo rushes off. The famous “Merry Widow Waltz” follows, and the prince and the widow waltz around the stage. The Baron, pleased with the possibility that the prince might be interested in the widow, thinks, however, that he has seen his wife Natalie going to meet Jolidon (as she in fact was). Natalie is saved when Sonia takes her place. In order to save Natalie’s reputation and to provoke a reaction from the prince, Sonia announces that she will marry Jolidon. The prince, realizing his feelings, then tells her a story about a princess who promised to marry another because her prince refused to “speak out.” The prince exits, announcing that he is off to Maxim’s, a Paris nightclub: “I’ll go off to Maxim’s. I’m done with lovers’ dreams. The girls will laugh and greet me. They will not trick and cheat me!” Sonia, knowing now of the prince’s feelings for her, sings, “He loves me I’m sure of it now.” Act II ends.

Act III is set in Sonia’s parlor, although the room has been redone as a replica of Maxim’s, complete with the dancing girls. After a cakewalk and a butterfly dance, the scene opens with Sonia telling the assembled guests that she has lost her fortune. If she is no longer wealthy, the prince feels that he can again freely express his love for her. In return, Sonia explains why she had announced her engagement to Jolidon. As far as losing her fortune, Sonia says, it consists only in the fact that she gives it to her husband. Marsovia is saved, and the two lovers again dance to the “Merry Widow Waltz.”

* * *

The Merry Widow was based on L’Attache d’Ambassade, an 1861 comedy written by Henri Meilhac. The opera’s libretto was written by Leo Stein and Victor Leon, who titled their version Die lustige Witwe (in English, The Merry Widow). Stein and Leon eventually engaged Franz Lehar to write the music. Lehar was born in Hungry in 1870 and had composed a number of operettas. The work was scheduled to open on December 30, 1905, at the Theater an der Wien, in Vienna. The management was so happy with the work that they mounted the production on a shoestring, using old sets and costumes from other operas.

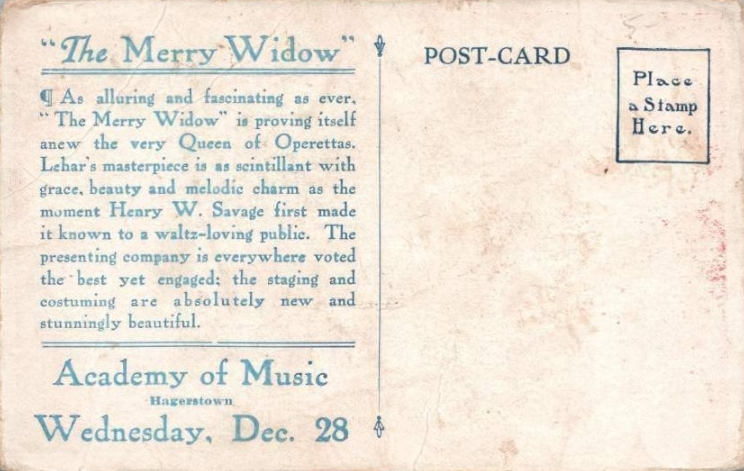

Merry Widow was fairly well reviewed but struggled at the box office through the early months of 1905. The longer it ran, however, the more it caught the public’s attention. By the end of the 1906- 07 theater season, it had been produced in theaters throughout the German-speaking world.

The first great success outside of Germany came with the London production at Daly’s Theater, opening on June 8,1907. The widow was played by Lily Elsie; the prince, by American comedian Joseph Coyne. The London production was a success, running 778 performances. King Edward VII, one of its many fans, saw it four times.

The American version was produced by Henry Savage, and the operetta opened at the New Amsterdam Theater, located on 42nd Street just off Times Square in New York City, on October 21, 1907. It starred Donald Brian and Ethel Jackson. That production ran for 416 performances, grossing about $1 million. Brian became a matinee idol and went on to play successful roles in many Broadway productions, before his death in 1948. Jackson, on the other hand, never achieved similar success. Her last Broadway appearance was with Paul Muni in the 1939 Key Largo. She died in 1957. Interestingly, the American version of The Merry Widow was edited slightly to remove certain lines and dramatic situations which seemed a little too daring for an American public.

As one historian notes, The Merry Widow proved to be “one of the most valuable stage properties in existence,” making Lehar a millionaire within two years of its premiere. It has been translated into more than 25 different languages and has been performed over a quarter of a million times, qualifying it for the distinction of being the most often played musical ever written. Lehar had a long and productive career as a composer and is regarded as the leading composer of operettas in the 20th century, although no single work of his ever again achieved the success of The Merry Widow.

The operetta does figure in a minor historical footnote. In Vienna, during its long run in the theater there, one of its frequent patrons was the young Adolf Hitler. Hitler’s continuing fondness for the operetta provoked considerable notoriety for the work and its composer during World War II. Once again art had triumphed over prejudice—for both the librettists were Jewish.

* * *

The Merry Widow has been “adapted” into a wide range of other art forms: at least three ballets and at least four films – first in 1907, then others in 1912, 1925, and 1934 starring Jeanette MacDonald, Maurice Chevalier, and Edward Everett Horton (as Popoff). Produced by Irving Thalberg and directed by Ernst Lubitsch, the film cost $1.6 million to make.

In the 1934 version the King of Marshovia sends the womanizing Chevalier off to Paris to woo and wed the wealthy MacDonald. Chevalier meets MacDonald at Maxim’s where she is disguised as a bar girl, the two fall in love, but when MacDonald discovers who he is and realizes why he is in Paris, she refuses his advances. Chevalier is subsequently put on trial in Marshovia for failing to perform his mission. The two, however, get locked together in a jail cell and the film, like the operetta, ends happily.

One last attempt came in 1952. It was a completely and deservedly forgettable Technicolor production featuring Lana Turner, playing the widow, whose name was changed to Crystal Radek and Fernando Lamas.

* * *

The world-wide success of The Merry Widow fell squarely in the golden age of the postcard. A substantial range of cards exist which document its various productions and capture its stars — especially its two leading ladies (Lily Elsie in England and Ethel Jackson in the United States) and its two leading men (Joseph Coyne in England and Donald Brian in the United States). But, like many influential and highly popular works of art, The Merry Widow‘s influence extended far beyond the stage.

The Merry Widow inspired a curious range of fads, most of which were items of apparel like shoes, gloves, and corsets. Other products which merely traded on the popularity of the name were luncheons, cigarettes, and the Merry Widow Cocktail (a concoction in equal parts of Vodka, Dry Vermouth, Dubonnet, and a dash of orange bitters).

But the most remembered association, and the one most documented on the postcard, was with the “Merry Widow Hat.” For the London production, designer Lucile, produced a distinctive hat for actress Lily Elsie who played the widow. The general characteristics of that hat influenced millinery fashion in both Britain and the United States for the next three years.

Since it was worn by a “widow,” the Merry Widow hat was, of course, black, often made of a dull-surfaced straw, with a deep crown covered in black tulle or black ostrich feathers. It was often paired with a white dress. The term, however, seems often to have been applied to any large hat. In fact, women’s hats throughout the first decade of this century, and their trimmings, had grown increasingly larger. Huge hatpins, as much as 14″ in length, were used to fasten the hats securely to a woman’s hair.

So large were these hats, that women were required in many places to remove them while attending the theater.

The Merry Widow occupies an important moment in musical theater history. Its success depended in large part upon the quality of its music; Lehar’s title waltz is still regarded as the most famous non-Strauss Viennese waltz. That waltz, moreover, does lie at the heart of what The Merry Widow must have represented to audiences in the first decade of the 20th century.

In writing about the waltzes in The Merry Widow, one historian has observed: “Set aside more or less forever were the regimented drills and classic ballets that had long dominated our [the American] lyric stage. From The Merry Widow on, softly swaying waltzes became the order of the night The principal love song and hoped-for hit of every new operetta was a ballroom waltz. Not unjustly, many historians see in these incomparable waltzes the seeds of what soon evolved into a rage for ballroom dancing.”

There is, after all, something exquisitely romantic about the waltz and about a world in which everything ends happily. Turn-of-the-century America was attracted to such a vision; it was still an age in which such illusions could be taken as reflections of how things might in fact be. Several decades later, with the experience of two world wars, a depression, an increasingly urbanized and mechanized life, the dawn of an atomic age, the triumph of the cellphone over personal interaction, and a worldwide Covid pandemic Americans may see things quite differently.

Interesting article that provided some great history and context for the Walter Wellman Merry Widow Wiles postcards that I recently started collecting. Thank you!

A 1908 U.S. special delivery stamp (#E7 in the Scott Catalogue) is known as the “Merry Widow” because the helmet of Mercury, as depicted, resembles the hats discussed in this article. https://www.matchandmedicine.com/product/e7-special-delivery-merry-widow-mnh/

That was a wonderful history of theatrical production in general and much about the favorite “Merry Widow”. It really had a broad influence, didn’t it ? And OH those giant hats !

I FORGOT TO SAY “WHAT WONDERFUL POSTCARDS” !!!