Hy Mariampolski

Remembering the

Mambo Dance Craze

Like all luscious dishes, the mambo is an amalgam – a mixture of dance and musical styles – tasty flavors representing sources in Afro-Caribbean religious rituals and romantic Latin-American melodies like the son Cubano. Its related song and dance styles including danzon, cha-cha-cha, rumba, pachanga and others, are usually encompassed under the collective term – mambo.

Imagine yourself at a club back in the 1950s: On a crowded dance floor, electrified couples are swept into a rapture, their swiveling and swaying bodies captured by piercing, driving brass instruments, trumpets and saxophones and exotic beats supplied by unfamiliar percussion instruments – congas, timbales, maracas, bongos and claves. The tight spaces and firmly wrapped bodies enliven the colognes, perfumes and pomades the dancers are wearing, the heat and friction producing a cloud that melds them into one. Their sweat intensifies, making the dancers already tight clothes nearly transparent as the moving spotlights focus down on them individually.

The Mambo Craze infected New York City nightclubs from the 1940s through the early 1960s. The trend can be traced to two primary factors: First, the tremendous immigration from Puerto Rico and Cuba. Second, the extraordinary visible success of a small cohort of performers with Caribbean roots – like Desi Arnaz, who played the leader of a mambo conjunto (music ensemble) in the era’s #1 leading TV show, “I Love Lucy.” Then, there was the superstar Xavier Cugat who excelled so much at both music and art, that the newly constructed ultra-chic club at New York’s recently renovated Waldorf-Astoria Hotel featured both of his talents. A wonderful 1940s linen postcard served as an exquisite souvenir for New York’s hottest club of the moment.

Coming at a historical moment when many young New Yorkers were seeking to shake off wartime doldrums and coupling was in the air, many could not resist a visit to venues in Greenwich Village, Spanish Harlem, Upper Broadway, The Lower East Side – now dubbed La Loisaida – and the Bronx, to learn a few moves and spice up the dance floors. Postcards of the era, illustrating the stiff competition going on between the nightclubs outdid each other in stylishness and verve.

The first one out of the gate as early as 1925 was El Chico in Greenwich Village whose Spanish owner Benito Collado created the mold that energized the genre. Take a classic Iberian interior design, enhanced with Spanish popular culture, such as images of bullfighters, and offer some classic Spanish dishes such as Caldo Gallego (broth with cabbage and mixed greens) and Paella Valenciana (mixed seafood over saffron-flavored rice.) This real photo postcard shows just the place to enjoy these dishes and others.

Spice it up with some Cuban and Puerto Rican offerings, such as Cuban sandwiches and Pasteles Borincanos (mashed plantains and pork wrapped in banana leaves) and even a Mexican dish or two like Chile con Carne (ground meat and beans) and you have the perfect combination to attract all sides of the emerging Latin population mix and keep them fueled for a night of frenetic dancing.

Some clubs took interior design to another realm of kitch by adding fake palm trees and applying layers of bright Caribbean colors. This was not limestone, bluestone and brownstone New York. The Nuyoricans had arrived.

Illustrations were also popular on promotional postcards, using traditional imagery and humor. The Spanish Cabaret, for example, illustrated its name with a bullfighter, a Toreador. Don Julio’s funny postcards followed the common marketing bromide that laughter makes a message more memorable.

The emergence and success of the Mambo Craze symbolized the ascendancy of Latino culture in America. New York was amid experiencing the “Great Puerto Rican Migration” which inalterably changed the city’s culture and streetscapes. People began leaving the Caribbean Island during the Depression believing that their opportunities were better on the mainland.

Puerto Rico, acquired as a U.S. Territory after victory in the Spanish-American War (1898) has held a unique status – neither an American state nor an independent country but something curiously in-between. Consequently, its residents could move to the mainland as American citizens without further encumbrance.

More Puerto Ricans came to New York during the war years as many were recruited by the ports and defense industries or to gain more stability while family members were serving in the armed forces. As air transport grew after the war, migration expanded as better air links were established between New York and San Juan, the island’s capital.

As Puerto Ricans grew to more than 10% of the city’s population, multiple changes could be observed in New York’s neighborhoods that encouraged everyone to expand their vocabulary and culinary awareness. Corner convenience stores became “bodegas” (wine cellar or convenience market) selling things like plantains and yuca along with everything else from cigarettes to Oreos. The front windows of local luncheonettes suddenly filled up with offerings of cuchifritos (deep-fried pork or seafood specialties), empanadillas (dough filled with seasoned meats), and pasteles. Vendors appeared at parks or as schools were emptying with colorful wagons topped with a block of ice selling piraguas (shaved ice sno-cones flavored with syrups).

You knew things were changing when the movie theater down the street suddenly switched its programming from films with American comedians Abbott and Costello to those with Mexican comic Cantinflas.

Young immigrants poured into this setting providing both the talent for the clubs and the service workers that churned out the clean tablecloths and dishes. They were the nightclubs’ regulars who would fill up half the dance floor modeling their moves for the visitors that appeared.

If they needed to practice their dance moves at home, New Yorkers could buy the LPs that exploded from record shops all over the city – from major record labels or from smaller aspiring producers like Montilla Records.

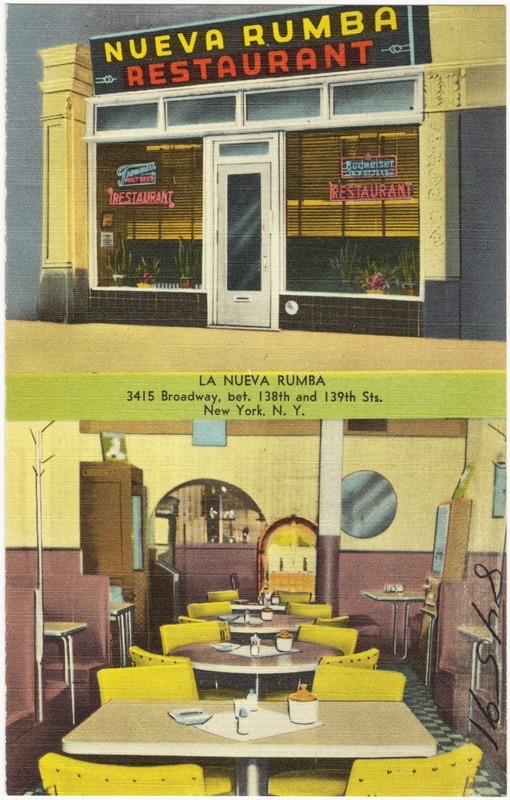

The most intrepid Americanos might venture off to Spanish Harlem’s Palladium, uptown to the Nueva Rumba or to the Teatro Puerto Rico in the Bronx. Popular Mexican singing cowboy Jorge Negrete provided an affectionate greeting and autograph to a New York fan at the Teatro Puerto Rico, showing that the Mambo Craze was not just a local curiosity but had engaged music-lovers from all over the Hispanic World.

Even New York’s Number One dance emporium Roseland, located near Times Square, organized events for its Latin fans as illustrated on this 1961 postcard mailing announcing a “Cha-Cha Championship.”

Over the years the Mambo Craze has gone from a movement to memory – off into the realm of literature. The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love (1989) written by Oscar Hijuelos (1951-2013) is a gorgeous elegiac work that traces the inner experience of a mambo performer during the period of the craze. It follows the conquests and failures, and mostly the anxieties and insecurities of an immigrant generation performer. This insightful and well-constructed work gained widespread acclaim for its author who became the first Hispanic to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1990.

Was there a real Mambo King? Yes, his name was Tito Puente (1923-2000,) shown in this chrome card from the early 1950s at the start of his career. The real Mambo King appeared in the movie version of the novel. Most of us remember him graying in middle age and older, leading an international musical style. Puente’s naval service during World War II entitled him to G.I. Bill benefits which Tito used to gain formal musical education at New York’s Julliard School of Music.

Even though the Mambo Craze, like other postwar New York music styles like Folk and Bebop, was thrown into a short period of retreat following the rise of rock music in the late 1960s, the music was developed and reinvented by Tito Puente and others like Celia Cruz, Tito Rodriguez and Carlos Santana and persists as the core of contemporary Latin music.

You can still get a piragua in New York – just find a vendor and ask for a tamarindo con crema (tamarind with cream) flavor. You’re certain to start hearing Tito Puente’s “Oye Como Va” going off in your head.

Good, but not complete.

Not intended to be a complete history of the Mambo in 1200 words, just telling a story about postcards and what it felt like in New York

It brought back lots of good memories, I was living in NYC then and used to go to Casa Cougat often. Loved to Mambo and Cha Cha.

I was familiar with Cugat’s name, primarily because two of his ex-wives, Abbe Lane and Charo, were frequent guests on television shows as I was coming of age. I didn’t realize he was also a caricaturist.

I moved to Miami in the late 70s. The early 80s I attended a Cuban festival “Calle Ocho” in the SW 8th. St, Latin neighborhood of Miami. I was lucky enough to see Tito Puente and Celia Cruz in concert. What a treat I will never forget. Myself and thousands of Latins dancing to the salsa beat.

If it wasn’t complete there was lot of well=written info and a good selection of cards of many different types. Wish I could have been there, but never got to that side of the states until much later. Thanks for an entertaining bit of history !