Timothy Van Staden

The Site Where Hesperus Wrecked

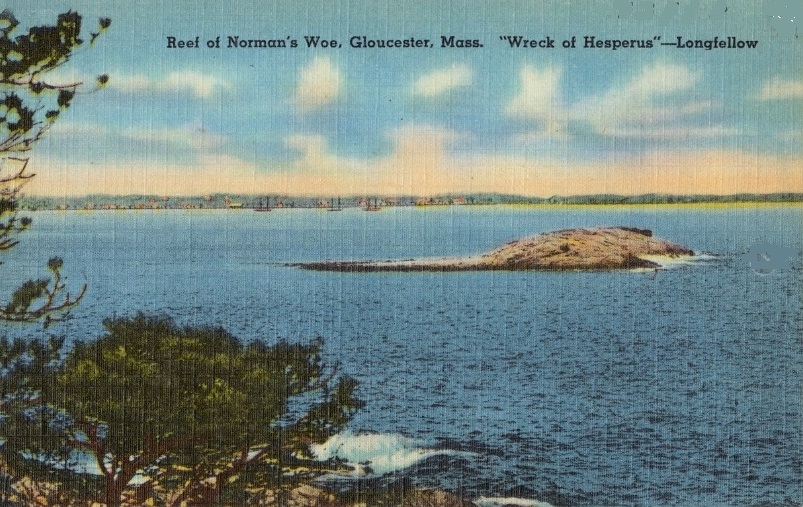

Is it possible that a rock has a personality? Perhaps! And, if it does; is it evil? If the Lorelei (see “The Story of the Lorelei” in Postcard History, February 15, 2021), along the Rhine River in Europe is thought about as a source of misery, there is a worthy rival in Massachusetts. In the far northeast of the state there is Norman’s Woe, a rock reef on Cape Ann, about a quarter mile offshore from the city of Gloucester.

The highest elevation of Norman’s Woe is about twenty-five feet, but when the tide is high the reef is totally awash and is completely hidden. There is a bell buoy about a half-mile to the southeast but it has failed on many occasions to warn of the danger.

The Norman’s Woe has been the site of many shipwrecks. Deadly ones! The oldest recorded was that of the Rebecca Ann. In a March 1823 snowstorm, ten members of the Rebecca Ann’s crew were hit by a wave that swept them to their death-at-sea – the only crewman to survived climbed onto a rock in the water that could well have been the “Woe”.

A violent storm in 1839, later to be known as the Blizzard of 1839 was the inspiration for a narrative poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. The wreck that night at Norman’s Woe was of the schooner Favorite out of Wiscasset, Maine. The next morning twenty bodies were found along the shore; one was that of an old woman tied to a broken mast.

The following year in the January 10, 1840, issue of the New World, Longfellow published his narrative under the title The Wreck of the Hesperus. The editor, Park Benjamin paid Longfellow $25.*

Park Benjamin, who in his day was a poet**, journalist, and editor and founder of several newspapers, not the least of which was the New World, a New York City weekly.

* The 2022 equivalent would be $700.

** Benjamin is now forgotten except for his poem, The Old Sexton.

* * *

Card No. 2 from a set of six, published in Boston; one of which is postmarked 1908.

Card No. 2 from a set of six, published in Boston; one of which is postmarked 1908.

The Wreck of the Hesperus is a story that tells of the tragic consequences of a Shipmaster’s ego. During an ill-fated winter voyage the skipper brings his young daughter aboard his ship for company. One of his experienced sailors warns that a storm is coming, but the skipper ignores the advice to stay in port. When the storm arrives, the skipper ties his daughter to the mast to prevent her from being swept overboard. She calls out to her father as she hears the surf beating on the shore, then prays for the seas to calm. The ship crashes onto the reef of Norman’s Woe and sinks; the next morning a horrified fisherman finds the daughter’s body, still tied to the mast and drifting in the surf. The poem ends with a prayer that all others should be spared such a fate.

The Wreck of the Hesperus

It was the schooner Hesperus,

That sailed the wintry sea;

And the skipper had taken his little daughtèr,

To bear him company.

Blue were her eyes as the fairy-flax,

Her cheeks like the dawn of day,

And her bosom white as the hawthorn buds,

That ope in the month of May.

The skipper he stood beside the helm,

His pipe was in his mouth,

And he watched how the veering flaw did blow

The smoke now West, now South.

Then up and spake an old Sailòr,

Had sailed to the Spanish Main,

“I pray thee, put into yonder port,

For I fear a hurricane.

“Last night, the moon had a golden ring,

And to-night no moon we see!”

The skipper, he blew a whiff from his pipe,

And a scornful laugh laughed he.

Colder and louder blew the wind,

A gale from the Northeast,

The snow fell hissing in the brine,

And the billows frothed like yeast.

Down came the storm, and smote amain

The vessel in its strength;

She shuddered and paused, like a frighted steed.

Then leaped her cable’s length.

“Come hither! come hither! my little daughtèr,

And do not tremble so;

For I can weather the roughest gale

That ever wind did blow.”

He wrapped her warm in his seaman’s coat

Against the stinging blast;

He cut a rope from a broken spar,

And bound her to the mast.

“O father! I hear the church-bells ring,

Oh say, what may it be?”

“‘T is a fog-bell on a rock-bound coast!” —

And he steered for the open sea.

“O father! I hear the sound of guns,

Oh say, what may it be?”

“Some ship in distress, that cannot live

In such an angry sea!”

“O father! I see a gleaming light,

Oh say, what may it be?”

But the father answered never a word,

A frozen corpse was he.

Lashed to the helm, all stiff and stark,

With his face turned to the skies,

The lantern gleamed through the gleaming sn

On his fixed and glassy eyes.

Then the maiden clasped her hands and prayed

That savèd she might be;

And she thought of Christ, who stilled the wave

On the Lake of Galilee.

And fast through the midnight dark and drear,

Through the whistling sleet and snow,

Like a sheeted ghost, the vessel swept

Tow’rds the reef of Norman’s Woe.

And ever the fitful gusts between

A sound came from the land;

It was the sound of the trampling surf

On the rocks and the hard sea-sand.

The breakers were right beneath her bows,

She drifted a dreary wreck,

And a whooping billow swept the crew

Like icicles from her deck.

She struck where the white and fleecy waves

Looked soft as carded wool,

But the cruel rocks, they gored her side

Like the horns of an angry bull.

Her rattling shrouds, all sheathed in ice,

With the masts went by the board;

Like a vessel of glass, she stove and sank,

Ho! ho! the breakers roared!

At daybreak, on the bleak sea-beach,

A fisherman stood aghast,

To see the form of a maiden fair,

Lashed close to a drifting mast.

The salt sea was frozen on her breast,

The salt tears in her eyes;

And he saw her hair, like the brown sea-weed,

On the billows fall and rise.

Such was the wreck of the Hesperus,

In the midnight and the snow!

Christ save us all from a death like this,

On the reef of Norman’s Woe

I had heard of the poem, but don’t recall reading it before today. The third line in the second stanza on the right side was cut off — it should read “The lantern gleamed through the gleaming snow”.