Editor’s Staff

The House of Seagram

and the National Victory Effort

In a free and open society there are no citizen handbooks for public behavior other than the Golden Rule, the Ten Commandments, and laws laid down in Public Codes by elected officials.

In wartime the rules change. Throughout history governments usually call upon their citizen artists to produce reminders that would otherwise seem excessively cautious or paranoid. From the American Revolution to what may have been the day-before-yesterday, poster art from coast-to-coast has been found in town halls, post offices, railroad stations, bus terminals, grocery stores, barber shops, and nearly every public space in any given city, town, or village.

When it becomes a necessity, spontaneous and commissioned art can factor into the spread of information for public awareness of problems and concerns. Two eras in American history when this kind of messaging was most successful were the war years (1917 to 1919 and 1941 to 1946) when the United States was a significate party in two international conflicts.

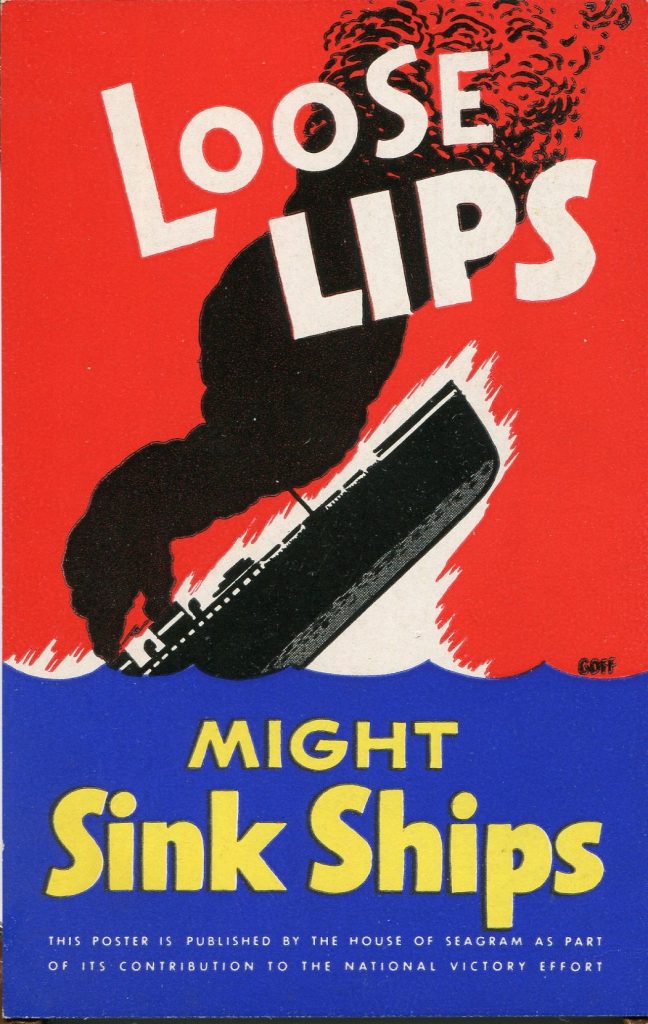

During World War II the Seagram Company, then headquartered on Lexington Avenue in New York City inserted several obvious concepts into the national dialog of Americans. They called their actions a contribution to the National Victory Effort. What they wanted was for people to use common sense. The campaign was to have those who knew war-secrets to stop talking about the war in ways that could undermine the war effort.

The phrase “loose lips” came straight from the Office of War Information early in 1942. It took very little time to become part of the national lexicon because the Seagram Company commissioned their own art-department director, Mr. Seymour Rinaldo Goff (1904-1992), to prepare a poster for the widest possible distribution.

The poster later became this postcard.

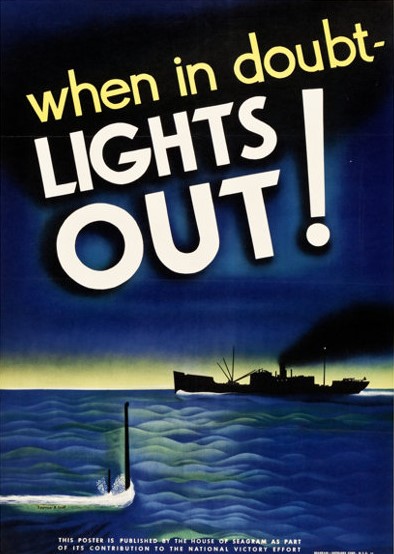

Seagram Corporation, in the months and years that followed published a series of posters that also appeared as a twelve-card set of postcards.

Each card has the following line at the bottom edge, “This poster is published by the House of Seagram as part of its contribution to the national victory effort.”

Seymour R. Goff, who joined the Seagram Corporation’s art department as director in the 1930s used the pseudonym Ess Ar Gee (also sometimes transcribed as Essargee or Essargeé, and at least two other variations), in his corporate work. The postcards, however, have become prime collectibles because they are signed, “GOFF” instead of the pseudonym.

The posters were created around an anti-espionage concept created by the government, which included a popular poster that first made use of the phrase “Loose Lips Might Sink Ships.” Unlike the posters, the postcards were distributed free to bars, restaurants, and left in government facilities along coastal cities and towns to discourage patrons from discussing the movement or schedules of ships and other wartime liabilities.

World War II is just a chapter in an American history book for most people alive today. It is a sorrowful state that the early 1940s is thought to be a romantic era in history. There is little that will change that but it’s worth noting that millions of lives ended in those years in horrible ways: genocide, battle wounds, starvation, and maybe even a broken heart. Many could have been successful scientists, teachers, artists, writers, and even politicians.

The other known cards are:

The only institutional collection of the Seagram Company war posters currently known is the Hagley Museum and Library in Wilmington, Delaware.

Interesting Article

This makes me think such a campaign for our political angst might be useful. 😁

Very interesting article and great postcards! I had no idea that there were so many postcards of this type produced.

The “Sink a Sub From Your Farm” card reminded me that one reason so few automobiles from the pre-World War II era survive is that many vehicles were scrapped in order to be turned into armaments.

Quite interesting.