George Miller

The Sea of Matrimony

June is the traditional month for weddings. Named for Juno, the Roman goddess of femininity and marriage, it seems a logical choice. Its popularity is certainly derived from convention, but also makes sense in another way. Since June is the graduation month, it marks a logical point at which two people, graduating from school and making their way into the real world, can begin life together. Well, it used to be that way — today they just move in with one another.

Every stage of courtship and marriage is marked by an elaborate set of rituals. And once the engagement is announced, the couple and their parents are caught up in a sequence of events that is perhaps as rigidly prescribed as anything in our culture. Given that weddings are both such special and ordinary events in our society, we expect that they were captured on postcards. Yet, surprisingly, this is not a common subject — either in terms of what was produced or in terms of what is collected today. There are a few wedding congratulations cards—such as the Taggart series 705, but it takes time to locate and build a good, representative collection of wedding-related postcards.

Wedding gifts

The custom of giving wedding presents was widespread throughout history. It was a way of acknowledging the start of a new family and of signifying the generosity of the giver. Traditionally, presents were practical, although often also ornamental. Today, a bride is more likely to receive luxury items—small electrical appliances, dinner or stemware, silver or crystal. Gifts were, and still often are, publicly displayed. In England at the turn of the century, newspapers frequently carried lists of wedding presents and their donors.

The wedding gift registry apparently began in the United States in 1901 at China Hall, a store in Rochester, Minnesota. The idea of registering a bride’s name with her pattern choices and then keeping a list of all gifts purchased for her proved immensely popular. By the 1930s and ’40s, most jewelry and department stores in the U.S. provided such a service.

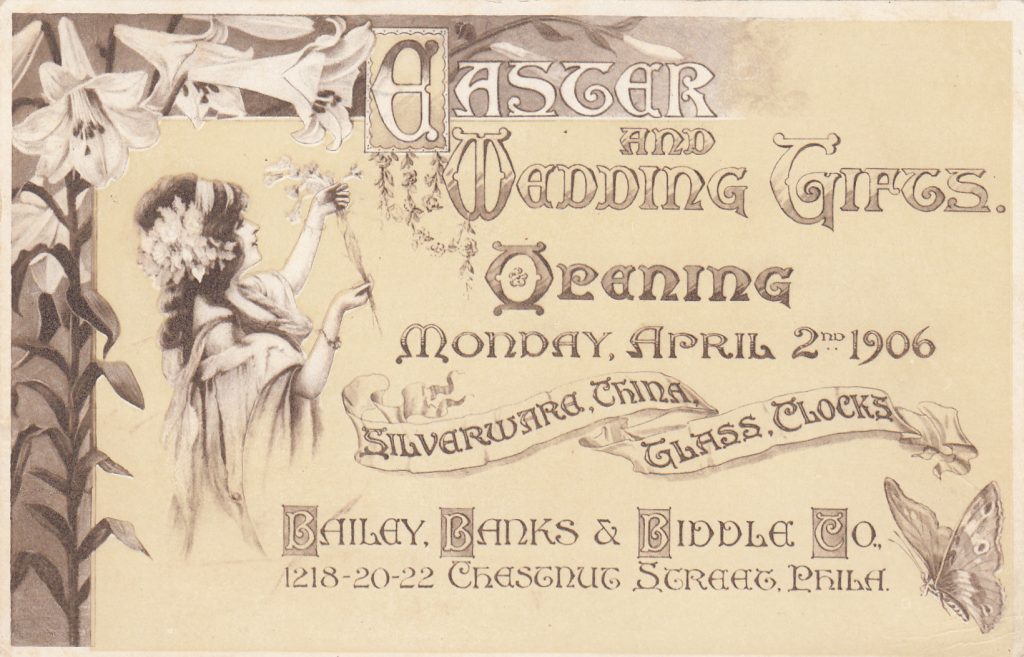

Postcard advertisements for wedding gifts are quite rare. One fine example is the opening of Bailey, Banks & Biddle Company in Philadelphia on April 2, 1906, selling Easter and Wedding Gifts such as “Silverware, China, Glass, Clocks.”

The Ceremony

Not every couple march down the aisle of a church after the ceremony to the bridal chorus (Here Comes the Bride) from Wagner’s opera Lohengrin — that wasn’t popular until the turn of the 20th century. The wedding ceremony, however, is highly ritualized.

Typically today, brides wear elaborate white gowns, which are modern additions intended not only to symbolize purity and innocence, but also to acknowledge wealth enough to buy an impractical dress (white) that will be worn only once. In the mid-1800s most women were married in their best outfit – not in a white gown. Even during the early decades of this century, women often wore their wedding dresses on special occasions during the first year of married life.

Rings are exchanged, although double-ring ceremonies were uncommon in the United States before the 1940s when American soldiers brought back this European custom. In our culture, the wedding ring is worn on the third finger of the left hand, a practice dating back to the Egyptian pharaohs who believed that this finger contained a vein that ran directly to the heart. A nice idea, but medically unfounded.

Brides carry flowers as symbols of life and fertility, a custom that originated in bouquets of strong-smelling herbs intended to drive away evil spirits. The couple is showered with food stuffs after the ceremony (rice in the United States) to insure fertility in marriage.

Today’s wedding is not complete without a photographer who captures every significant moment of the day. But such records are not available on postcards. Photography was still new to average people, and churches did not generally allow photographs to be taken during the ceremony.

Couples did, however, use the postcard to record the wedding and during the postcard era, couples chose to be married in locations outside the church.

The cards above depict two popular options: out-of-doors beneath an elaborate arch of greenery and the marriage parlor, like that of Oscar L. Hay in Jeffersonville, Indiana, where civil ceremonies were quite common. Presumably Magistrate Hay used his postcard to promote his marriage business; this one was postally used on July 24, 1913, by a bride. Her message was, “We have just got married.”

The Wedding Cake

Whatever else is served at a reception following a wedding, there must be a wedding cake. Until the 1860s the traditional wedding cake in the U.S. was a dark and spicy fruitcake. The “white” wedding cake is a fairly new phenomenon. As with everything involved with weddings, superstitions connected with the cake abound, e.g., it is bad luck for a bride to bake her own wedding cake; a bride who tastes her cake before it is cut, forfeits her husband’s love; and a bride who saves a piece of wedding cake will ensure her husband’s fidelity.

The wedding cake is the subject of a postcard set published by Morris and Bendien. The cards, featuring colorful, but naive  designs signed by Frederick Duncan, follow a couple through their wedding day. I’m not sure how many comprise the set. Currently there are two others known; Forever and Ever [the wedding kiss] and Off for the Honeymoon.

designs signed by Frederick Duncan, follow a couple through their wedding day. I’m not sure how many comprise the set. Currently there are two others known; Forever and Ever [the wedding kiss] and Off for the Honeymoon.

Aftermath

Part of the wedding tradition are jokes—it’s all so romantic and storybook-like now, but just wait.

A for-certain giggle comes from “The Safety Guide for Those Contemplating a Trip on the Sea of Matrimony.” This 1910 die-cut postcard published by J.I. Austen Company, Chicago, opens to reveal a folded colored map of the perilous course through the Sea of Matrimony. The topographical features assume meaningful comic shapes — things like a rolling pin, a series of women’s heads (in the Servant Archipelago) and a diaper pin and pacifier in the Isles of the Little Blessings. The inside copy describes the itinerary.

Starting at Hallaballoo Bay, in clear water, the sailing is fine, and bright passing through Wedding Joke Straits and to your first stopping off point, Honeymoon Island. Leaving that place and touching First Quarrel Reef you still are in shallow waters and as telephone connections can be had with Charivari Point it is advised to keep in cabin until Boo-hoo Bay has been passed. By this time you will be on your “Sea-legs,” but are cautioned against Cape Henpeck, Club Island, and Foot-lightia near Chip-in-Bay, where many a good sailor has been wrecked. Passing these points on your journey, danger is again scented along Cooking School Point and Sinking Islands near the tenth Meridian. If surviving these danger lines, great care must be exercised in navigating along the Servant Archipelago. Pirates, tyrants and great luminaries abound in these Islands and it is indeed a skillful Navigator who can steer clear in these waters. Shallow water is again encountered at Boarding House Island, Hotelia and Lovinacottage Island and when once rounded the balance of the journey promises well. Good cheer and happiness arises when in sight of The Isles of Little Blessings. By this time and when Comfort Cove is reached, the 50th meridian line is seen by the glasses and in the distance hove Snowy Peak and Mt. Baldy. The journey through the Sea of Matrimony nears its close when Golden Wedding Island is touched. When a landing is made at Mt. Joy your journey will have ended. The route shown herein gives the clearest and most entrancing views of the majestic peaks, which are never lost to view. While high speed has been attained in the voyage, we hope it has not been at the sacrifice of safety and comfort. At an average of ten lover knots per hour, Golden Wedding Island should be sighted on schedule time and the final passage to the land of Joy and Peace and Heart— Desire should be in clear water and easy sailing.

Anniversaries

For those who survive the trip on the Sea of Matrimony, there are annual anniversaries to be celebrated. The traditional anniversary gift list runs annually from years 1 to 15. After that, presents are given in five-year intervals (they get much more expensive, so that’s the compensation!). I’ve never seen the full range of wedding anniversaries represented on postcards.

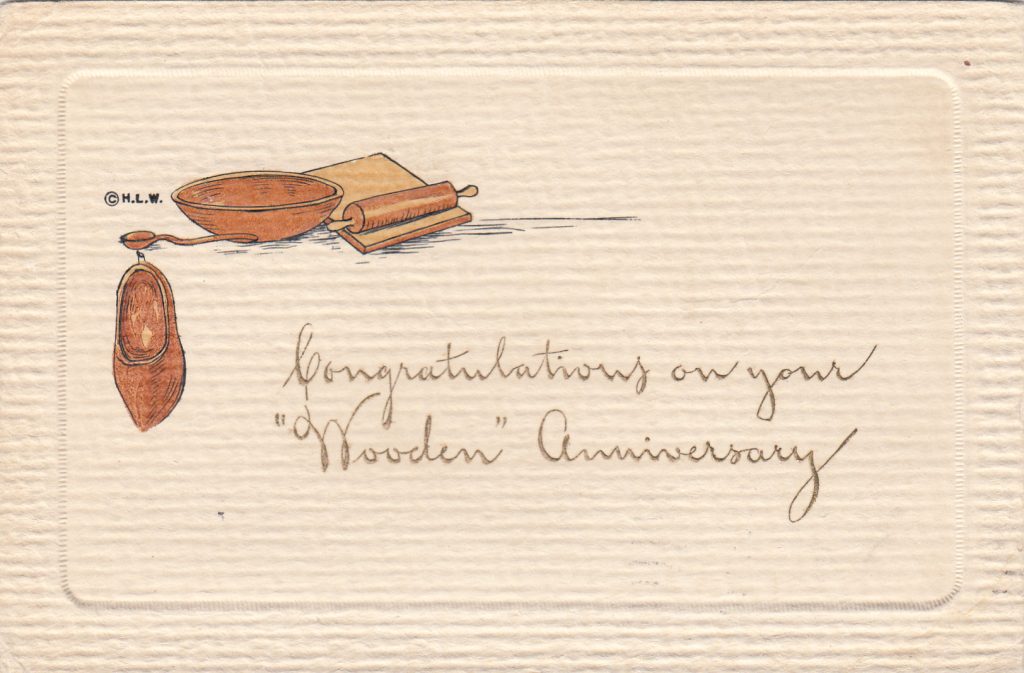

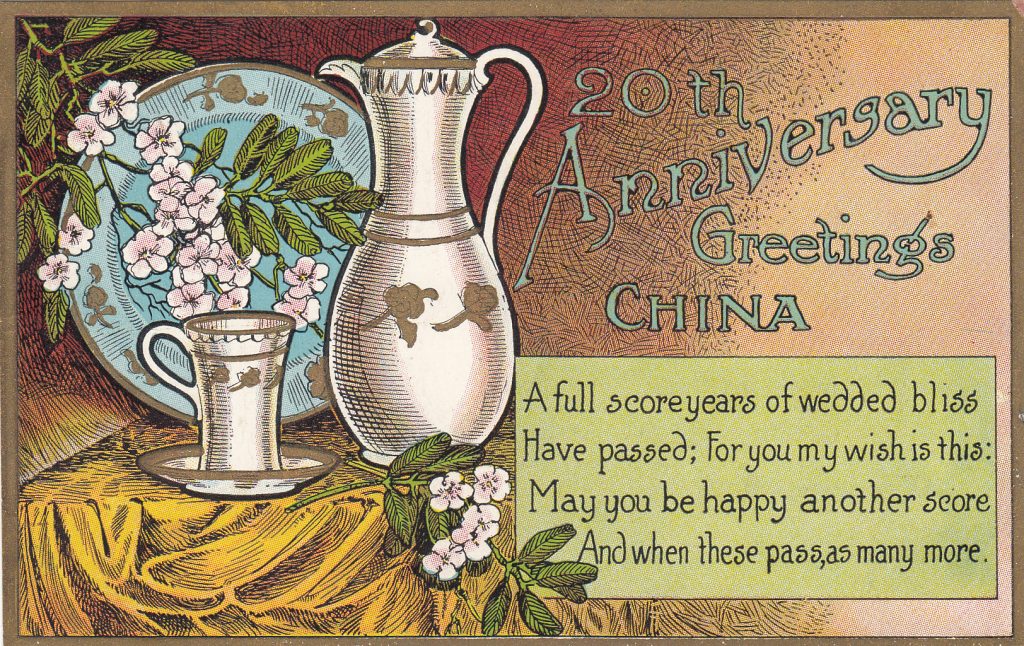

The H. L. Woehler, Buffalo, New York, card used in 1911, celebrates the “wooden” anniversary (the 5th year) and, the card used in 1910, commemorates the “china” year (the 20th).

Few of us will ever hit the big numbers. A fitting place to end is with this real photo postcard with these touching photos of Uncle Henry and Aunt Callie. The message notes the day and event: “October 18, 1908. Fiftieth wedding anniversary.”

Although “Here Comes the Bride” is from Lohengrin, the post-ceremony march is from Felix Mendelssohn’s incidental music for the Shakespeare play A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Clever and unique article. Enjoyed the interesting post cards.

A great article and great cards!