Editor’s Staff

A Quirky Piece

of Election History

The United States conducted its 39th quadrennial presidential election on Tuesday, November 5, 1940. There were six candidates, four of whom had names now forgotten in history, but when the votes were counted, a Republican New York businessman named Wendell Willkie and his running-mate Charles L. McNary of Oregon lost to the incumbent President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his running mate Henry A. Wallace. (Electoral vote count was 449 to 82.)

That election would prove to have worldwide consequences. With the country slowly emerging from the Depression and a second world war on the horizon in Europe, the one thing that most voters agreed on was strong leadership. The President had already served two full terms; Willkie was a complete newcomer to politics who had never run for public office. He knew nothing about conducting a campaign but did manage to revive opposition party loyalties in parts of New England, the Great Lakes region and part of the Midwest.

The Republicans met in June to nominate their candidate. When Willkie arrived, he had more delegate votes than any of the other leading contenders: Taft of Ohio, Vandenberg of Michigan (both U. S. Senators) and New York’s district attorney Thomas E. Dewey. Each was an isolationist who wanted to stay out of international affairs at all costs.

In July the Democratic Party convention took place in Chicago. Roosevelt’s only real battle came when Vice President John Garner turned against him over his economic policies. Henry Wallace replaced Garner.

The campaign followed and all stops were pulled. From mid-September until election day, some weeks were touch-and-go, others were to-and-fro (please forgive the loquacious political jargon) but Roosevelt kept a nine to twenty-two percent lead in the polls. Willkie hammered FDR with denouncements of his seeking a third term with phrases like “If one man is indispensable, then none of us is free.” On the other side the campaign posters vilified Willkie for seeking office without knowing how to be a good Republican.

* * *

Willkie died in October 1944; Roosevelt passed in April 1945. There are Americans who remember them, but their numbers are dwindling. The middle-years (1939-1953) of the twentieth century came with many more surprises than expected. Heartbreak and happiness did not come in equal parts. Lives were lost by the millions in the 1939-1945 world war and later in Korea, but no history should be lost even if it is curious, strange, weird, and unusual.

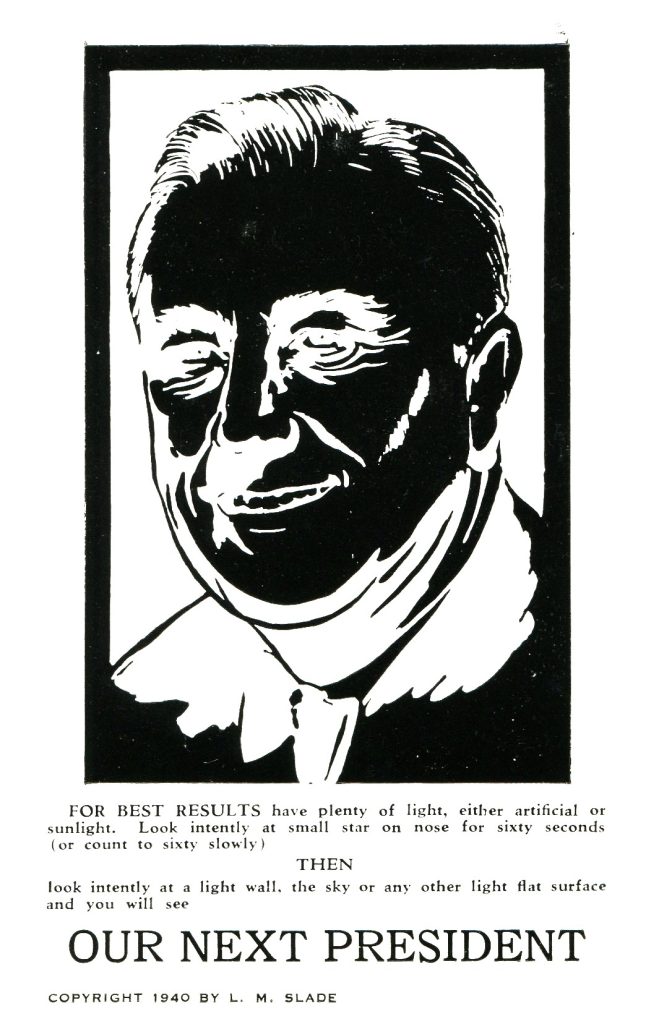

Postcard history has two postcards that exemplify all the above. They are curios and certainly unusual and they represent a faction of American citizenry that lives on the fringe.

I would try, if one ray of hope existed that it would be helpful, to find someone who may remember the Slade family of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Sometime apparently in the late-1930s, Arthur Slade and his wife Lorraine moved into a Dutch Colonial style, eight-unit apartment building at 4409 W. Lisbon Street in Milwaukee. He was just over 50 years of age and was a very successful Fire Insurance Salesman. Lorraine was 48. Their 22-year-old daughter Virginia lived with them in Apartment #3. Virginia worked as a court reporter in the Milwaukee County courthouse.

Assumption is always part of stories like these, so here is how years of experience have taught the skills to assume a story’s conclusion.

In the bottom left corner of each card is a citation that a copyright was sought in 1940 by L. M. Slade for the image on the cards. Assumption #1 is that L. M. Slade was the artist.

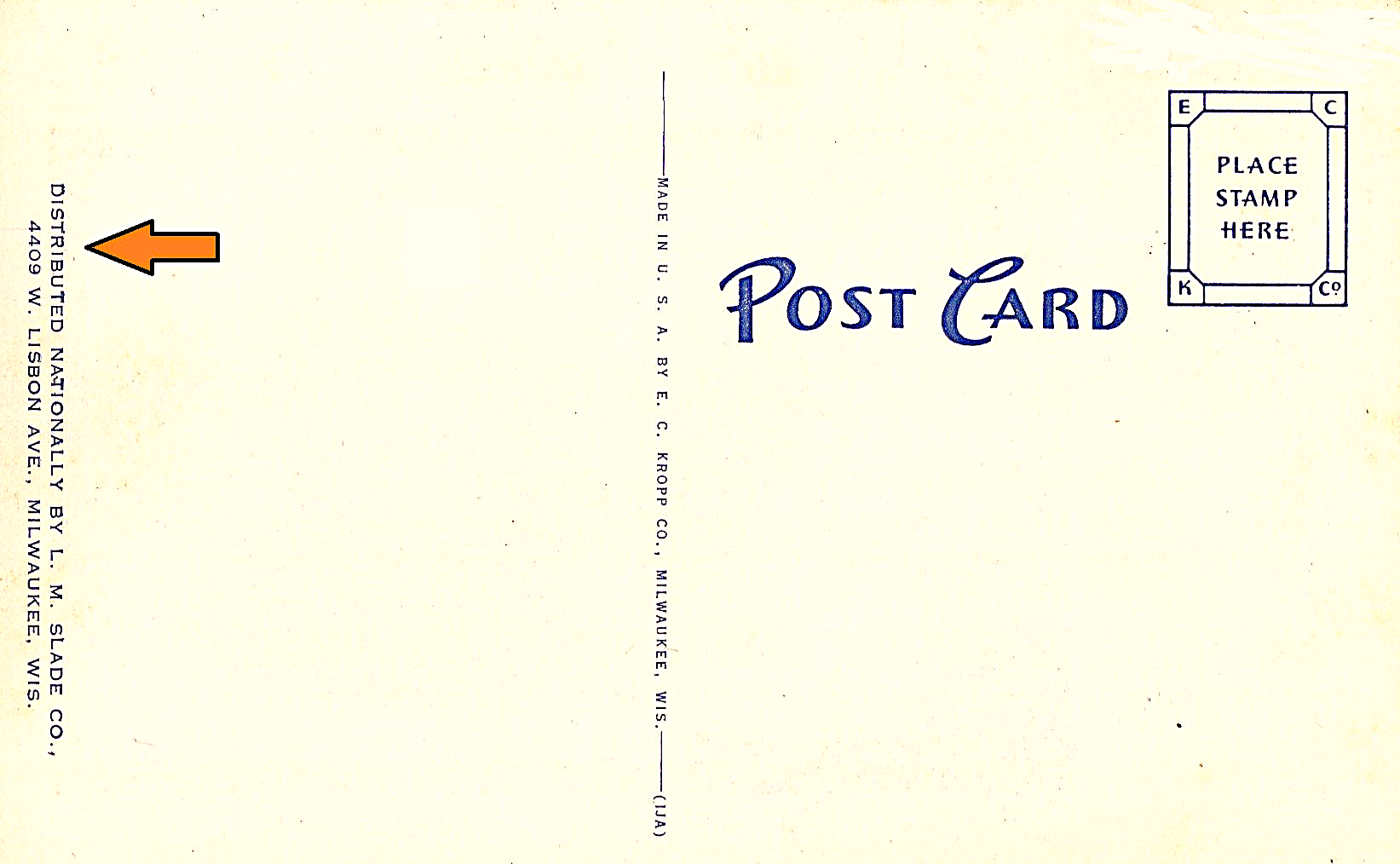

There is a distribution notice on the reverse of each card concerning nationwide availability by L. M. Slade Company at 4409 W. Lisbon Ave. Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Assumption #2 is that the cards were for sale by a company that did not exist.

Assumption #3 would be that the artist did not care who Our Next President would be as long as she could sell lots of postcards.

Assumption #4 is that history has Lorraine Slade to thank for these two pieces of weird postcard history (and there may be others) although in neither Population Schedule of the sixteenth (1940) nor seventeenth (1950) Federal Census of the United States, does Lorraine claim to have an occupation or income.

Lorraine’s husband Arthur died on June 1, 1955, she continued to live on West Lisbon Avenue for the next twenty-five years until she died on January 15, 1980 at age 78.

The principals are all dead, Milwaukee was not the Naked City, but the iconic line: “There are eight million stories in the naked city. This has been one of them,” is totally apropos.

I grew up at 4612 W. Lisbon Avenue in the 40’s so she would have lived on the other side of the street The area didn’t have a postcard factory or business that I remember

The third-place candidate in the race was Norman Thomas of the Socialist Party. One of the116,599 votes he received was cast by my maternal grandfather. During the run-up to the 1948 election, a teacher asked my mother which candidate her parents were voting for, and my mother replied, “Thomas.” The teacher rebuked her, saying: “Do not refer to Mr. Dewey by his first name.” Mom’s rejoinder: “Not Dewey, Thomas! NORMAN Thomas!”

So, what happened to 22 year old Virginia? Quirkly little tidbit. Thanks

There are still so many questions. It would be fun to know. What about an index for Milwaukee newspapers? Is there such a reference? Perhaps some of these questions might be mentioned and we might be able to learn more !!