Oliver Pollak

Herman and Ella Go to Russia

Some stories require postcards. Some postcards require stories. It can be a happy marriage.

Omaha journalist Ella Fleishman Auerbach (1894-1972) and her capitalist real estate and insurance entrepreneur husband, Herman Auerbach (1886-1950), loved to travel. During the First World War they volunteered to serve the Jewish Welfare Board, she in France and he in Texas. They married in 1922. Ella wrote two books and many articles, and Herman made money.

The United States broke diplomatic relations with Revolutionary Russia in 1917 but reestablished them in 1933. In 1937 Ella and Herman decided to visit the Soviet Union where his mother and brother lived. Ella wanted to see where her mother and father came from. They were interested in Jewish causes and wanted to see Soviet Depression era accomplishments.

Ella’s and Herman’s exploration and enjoyment were facilitated by luxury steamships, hotels, airplanes, trains and busses.

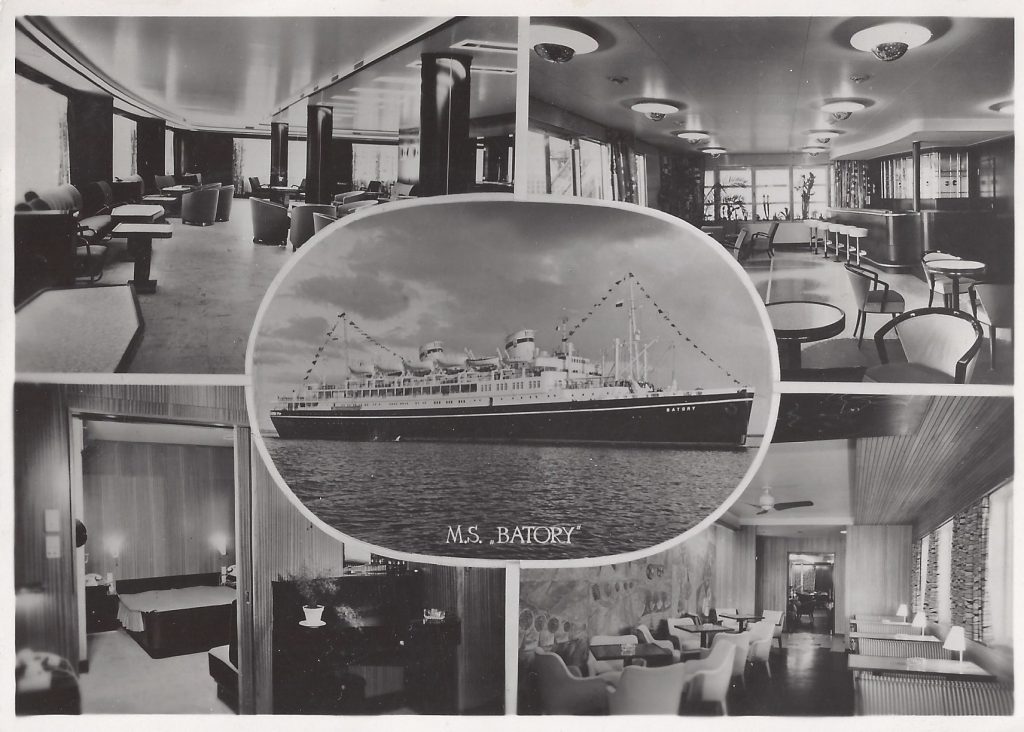

They set sail on the Batory, a Polish ship in the Gdynia-America line named for Stefan Batory a 16th century Polish king. The 14,000 ton ship, built in 1934 to carry 760 passengers, departed in early July 1937. As a troop ship it held 2,200. It participated in the Dunkirk evacuation and took children to Canada and Australia. It was scrapped in Hong Kong in 1972.

Ella wrote letters and postcards. She wanted to send postcards to Bucky Greenberg, a twelve-year-old Omaha boy who collected postcards and stamps. Unfortunately Russian postcards were in very short supply. Omaha friends and relatives had to settle for letters. As Ella and Herman explained to her friends Joe & Vy:

“I combed the town for a different kind of stamp for Buckie – feel I am “letting him down” on the stamp matter Russians don’t write many letters apparently – one generally goes to the P. O. to get them for even hotels do not always have them – and, as Herman explained: paper is scarce and good postal cards not available even in beauty spots [tourist attractions] where you would think they would be plentiful. Tourists grab them up but Russians are not keyed up to see the possibility of providing a few extra, since there is a big demand!”

Herman wrote on August 8, 1937, from Yalta:

“We are constantly on the go and observing new things. For lack of time and lack of paper – (paper is very scarce in Russia) we of course write very few letters. Next week Aug 16th our stay in Soviet Union is coming to a close – then into Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and home. Of course I am looking forward to my meeting with my mother.”

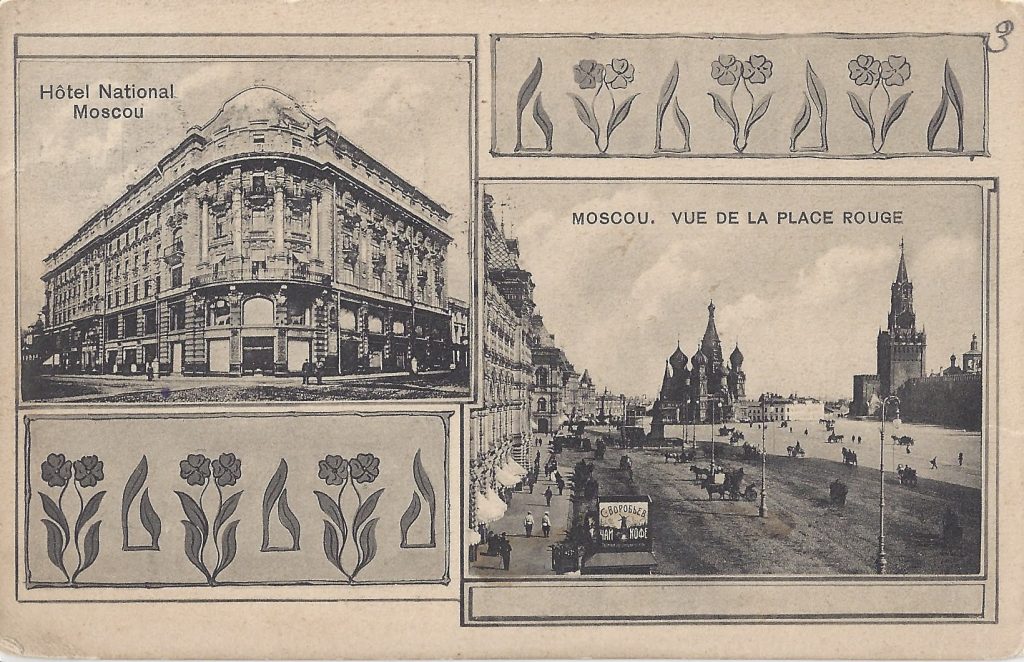

The Hotels National and Metropol exuded a cosmopolitan atmosphere. Ella and Herman travelling in style stayed at the swanky National which opened in 1903 directly across from the Kremlin.

Architect Alexander Ivanov designed the Hotel National. Construction started in 1901, but plans to add two floors were cancelled because of the world war. Nationalized by the Soviet government in 1918, it returned as a hotel in 1932. It is a five star hotel with 202 bedrooms, 56 suites and two restaurants.

In 2016, Amor Towles published A Gentleman in Moscow. The novel tells of a Russian aristocrat, Alexander Rostov, who was tried for anti-revolutionary activities and sentenced in 1922 to house arrest in the Hotel Metropol. He lived there for many years in a suite of rooms, but was now reduced to very cramped quarters. If he left the hotel he risked execution. He raised an adopted daughter, had an extended relationship with a Russian actress, and escaped around 1954.

This postcard of the Metropol was sent from Moscow to Copenhagen in 1911. It shows gardens and landscaping in the foreground which do not appear in images from previous years. Those cards featured horse drawn carriages and wagons, men in hats and long coats, gardeners, trams, streetcars, or trolleys that ran on rails. Post World War II views show cars and busses. There is a 1975 vivided colored Intourist card that shows two pluming fountains and gayly dressed visitors. The caption is in five languages.

William Walcot, born in Odessa in 1874 in a mixed Scottish Russian family designed the Hotel Metropol. Built in 1899 it had a dome roof. The Bolsheviks nationalized it in 1918 to house Soviet bureaucrats. It returned as a hotel in the early 1930s. It has 365 rooms.

Towles mentions the National Hotel in the Rostov-Metropol story. One episode, recalls pre-revolutionary Francophile affectations and pretentions. A Canberra Times reviewer calls it an intrigue about “assembling the ingredients for a bouillabaisse.” Alex and two hospitality and culinary workmates, the triumvirate, met daily to prepare for guests, dignitaries and high ranking Soviet officials. They connived to prepare the Marseille culinary delicacy bouillabaisse which required fifteen ingredients. Try as they might they could not get it together. With a novelists creativity the two missing ingredients, haddock and mussels destined for the Hotel National arrived by error at the Metropol creating a gastric delight.

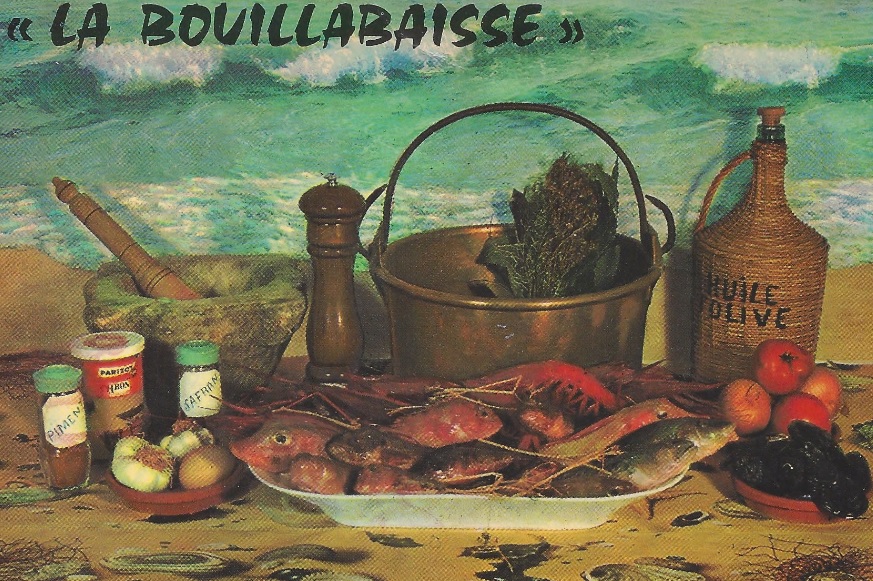

These are Mise en Place French cuisine postcards, proudly and colorfully depicting ingredients, preparation and presentation echo Towles fictional “Night of the Bouillabaisse.” This card with a crashing surf in the background produced in Nice provides a recipe on the back serving six.

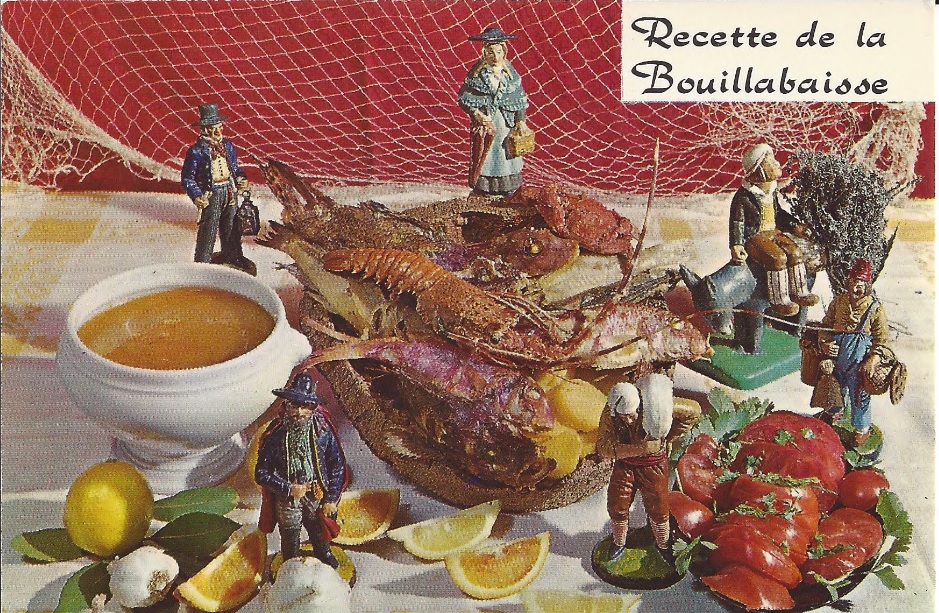

This card with a fishnet in the background was produced in Paris. The recipe on the back is attributed to the consummate French chef Emile Bernard (1826-1897) who wrote a series of recipe books, La Cuisine Classique. According to Wiki he cooked for the governor of Warsaw, the French Foreign Affairs Ministry, and the King of Prussia.

This postcard of Arbat Square, not one of the “beauty spots,” by Emmanuil Yevzerikhin, is postmarked September 9, 1937, a month after Ella and Herman left Moscow. The Moscow transport depot includes trams/trolleys, busses and taxis. Irene writes “Lieber Daddy!” and closes “Greetings and a kiss.” The card went to Ashiya, Japan via Siberia.

Yevzerikhin (1911-1984) born in Rostov-on-Don moved to Moscow in 1934. His wartime photography included the Battle of Stalingrad (August 1942 to February 1943). The Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center in Moscow exhibited his work in 2013.

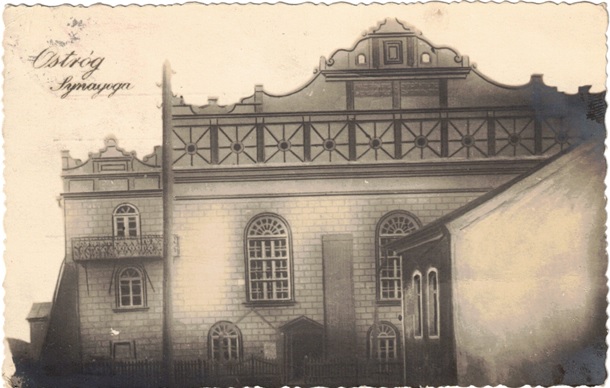

Ella wrote, “Our trip grew better and better after we left Moscow.” They sent this postcard of the Ostrog Synagogue from Ostrog, Poland on August 19. From 1919 to 1939 Ostrog was a Polish border town.

They wrote, “This synagogue is 1000 years old – according to local elders. Suspended from the ceiling is a bomb which crashed into the wall during a war in the 17th century without harming a single Jew who had taken refuge there.” Germany and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact on August 23, 1939. The Soviet Union annexed Ostrog in 1939. The Nazis seized the town in July 1941 and murdered thousands of Jews.

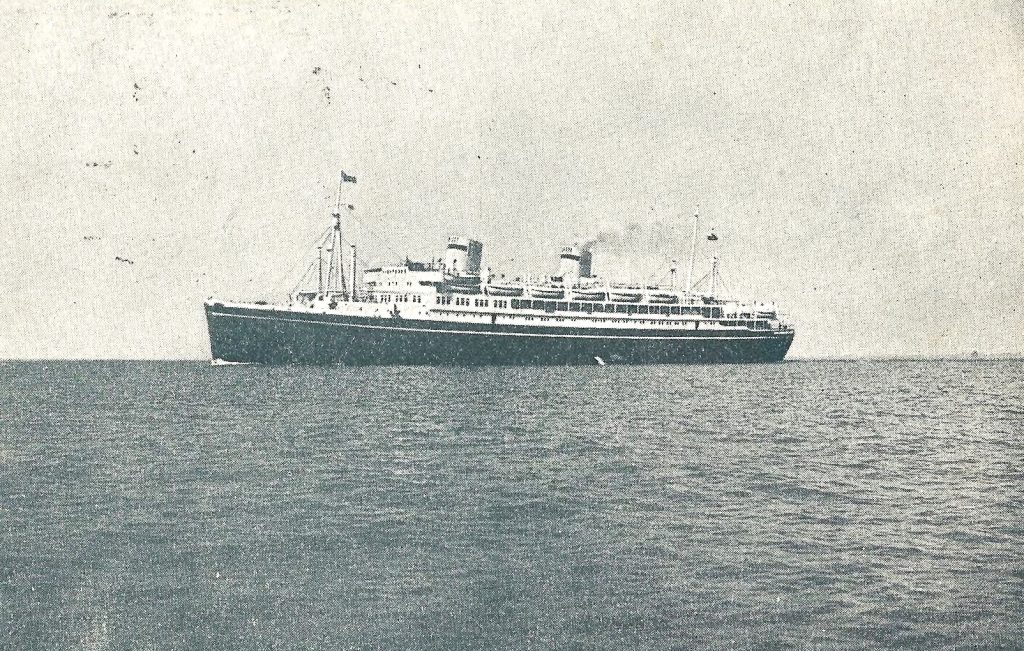

On September 2, 1937, Ella and Herman departed Europe for New York on the Pilsudski named for Marshal Jozef Pilsudski, Polish Chief of State and Prime Minister between 1918 and 1928. In 1934 the Polish and Italian government collaborated to build the 14,294 ton Pilsudski. Poland paid Italy with coal. Launched in December 1934 it carried 773 passengers. The British turned it into a troopship. Either a mine or a torpedo sank the Pilsudski in November 1939.

The Omaha press interviewed Ella and Herman. They had several speaking engagements. The shortage of paper and postcards and Joseph Stalin’s murderous Great Purge or Great Terror that ran from August 1936 to March 1938 killing 700,000 to 1.2 million people, went unmentioned.

The Soviet command economy was praised for conquering unemployment in the midst of a world depression. Moscow postcards featured bridges over the Moscow River. Herman praised the rapid bridge building program, but doubted the Russian bridges would endure because of shoddy work.

Ella and Herman continued to travel. The State Department persuaded them to cancel their 1941 cruise to Brazil. During the Second World War Ella volunteered in a hospital and Herman was a finance consultant to the U. S. Treasury. They finally made the Brazil trip in 1947. Herman had a serious heart attack in Buenos Aires and died in Omaha in 1948. Ella continued to travel and reported from China and Israel.

These postcards are all the more precious since we probably won’t be traveling to Russia for the next few years. Thank you for this article.

Enjoy the connections to Nebraska.

Fascinating.

History at its best! Also Gentleman in Moscow great read.

I’d like to know what makes of cars were used for the taxis depicted in the Arbat Square postcard, since Russia did have an automobile industry by 1937.

I had to chuckle when lack of paper was mentioned. Since they lacked toilet paper. In major hotels,yes, in the country,no.