Hy Mariampolski

Comedy Tonight

Comedy has always been a feature of the human condition. We seem to have an innate need to laugh at and disparage others when we confront funny characters and situations. Psychologists talk about schadenfreude, the kind of joy people experience at seeing the misfortune of others, like the way we inadvertently laugh when the doors slam on someone who’s been running to catch the train.

In 20th century America, astonishing advances in media technology – high-speed printing, photography, film, voice recording, television and video recording – stimulated the creation of new forms of media and entertainment. It was no surprise that new kinds of comedy and comedic performance were developed. Images of many of the era’s pioneers, of course, made it onto postcards.

Ancient and medieval royalty and plutocrats could keep a jester on retainer to lighten up those long soggy winter nights. Worldwide societies have had special holidays, celebrations and festivals devoted to comedy. Saturnalia, the Feast of Fools and Carnival were dedicated to subversion of the conventional order using copious amounts of alcohol, behavioral license, costumes, buffoonery, caricatures, role reversals, gender play, cross dressing, satirical put-downs of political and ecclesiastical leaders, everything comedians continue to do to get a laugh.

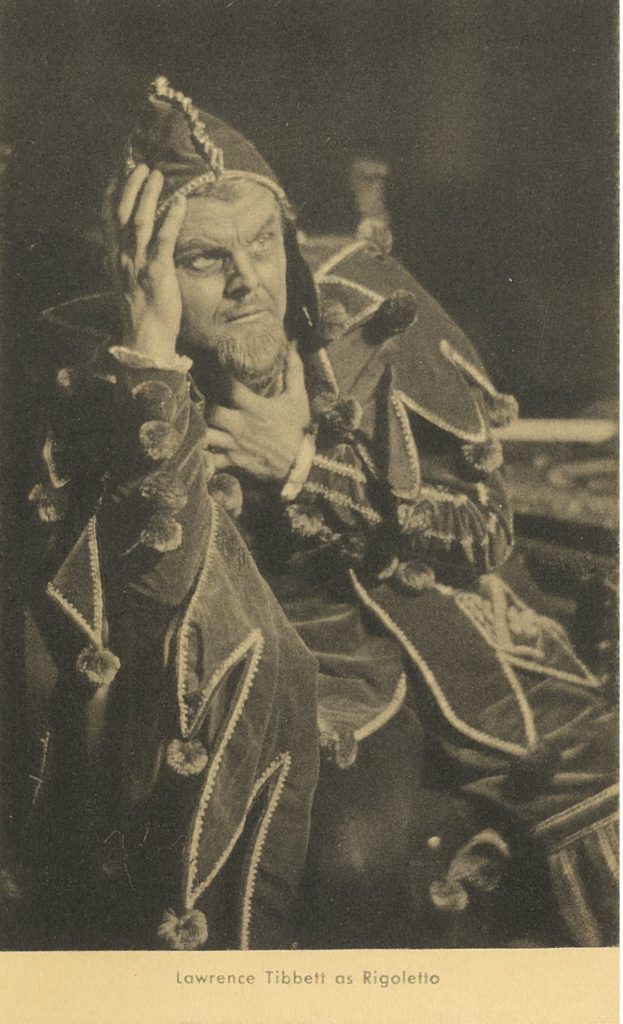

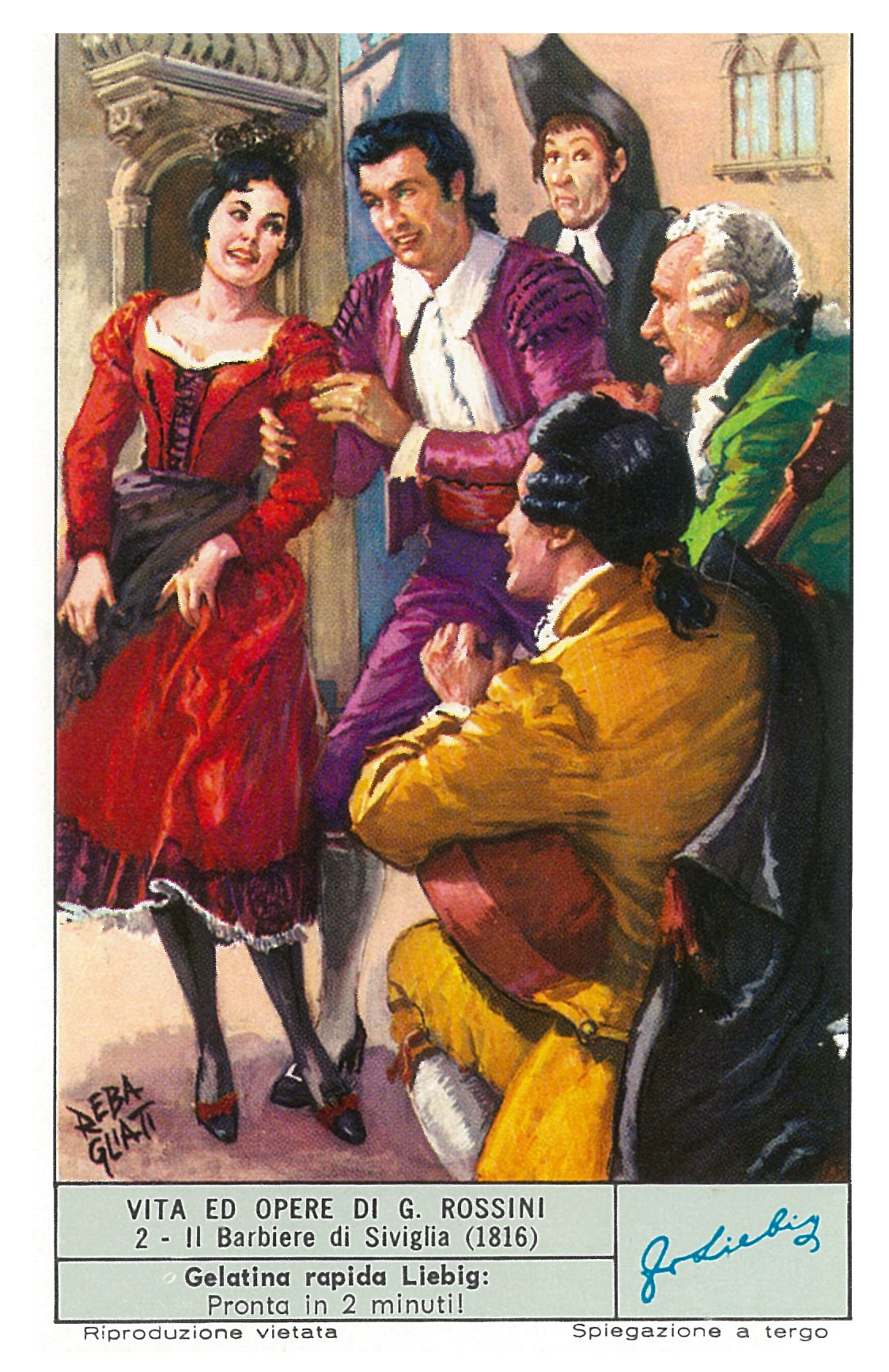

What was originally a communal celebration of hilarity eventually became professionalized as comedic performance. By the late Renaissance, we saw the emergence of such forms of theatrical expression as Shakespearean comedy, Commedia dell’arte and Opera Buffa (comic opera) which often use stock comedic characters and stock situations to provoke laughter and delight. A good example is a comedy of manners created in Vienna in the Italian language based upon the work of a French playwright writing about the Spanish nobility on the eve of the French Revolution’s outbreak. Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro) is an Opera Buffa composed in 1786 (and still popular) by

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, based upon an Italian libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte. Figaro, the servant of Count Almaviva, is about to marry Susannah, the servant of the Countess, Rosina. However, before the marriage takes place, the Count wishes to exercise his Droit de Seigneur, the feudal custom giving the Lord of the Manor the privilege of sexual access to any woman in his household on the eve of their weddings. The hypocritical Count, of course, has renounced this vestige of the barbaric past but seems eager to have one last dalliance. Susannah seems charmed by the attention but will not yield without resistance. That’s the comedic situation and, naturally, everyone in the baronial household has an opinion about it and wishes to take part in its resolution.

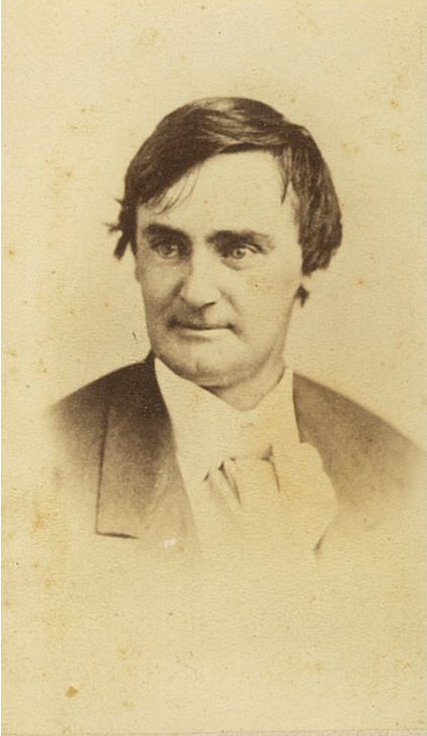

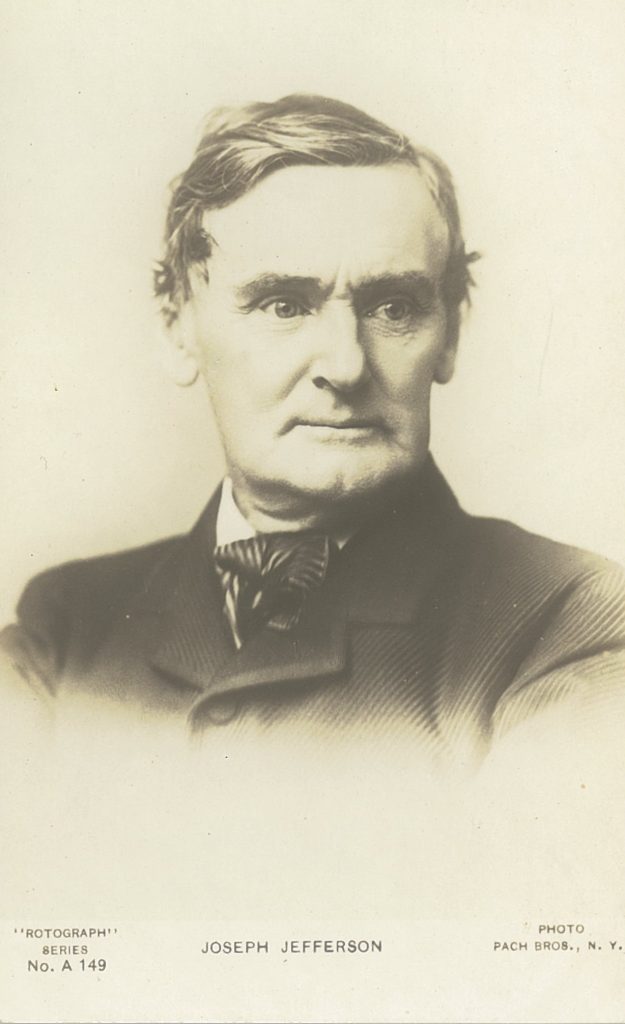

As the 19th century edged into the 20th, we saw the emergence of the comedian. The funny man usually made people laugh by being in some situation of distress brought on by difficulties of perhaps, manners, sexuality, intelligence or class relations. For Joseph Jefferson, the leading comedian of his age whose career spanned the carte de visite era of collectibles into the Postcard Era as represented on this Rotograph real photo, the distress was playing Rip Van Winkle, a character created by Washington

Irving in 1818. Van Winkle, already a ne’er-do-well complicates his life situation by falling asleep for 20 years and waking up into a different era.

As the comic arts changed at the turn of the 20th century, the stage comedian was defined by a funny role and by performing in a comedy – usually set off by comedic foils, intended to make him seem funnier by adding, complicating or displaying insensitivity to his distress.

A new type of comedy was created by the rise and overwhelming popularity of a new art form in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that made humor characterological and not situational – vaudeville. Comedy “acts” were created that had to compete against all the other vaudeville acts assembled for a program: singers, dancers, magicians, escape artists, animal trainers and so on. The new “professionalized” comedian was inherently funny and, in a reversal of the traditional standard, made the situation funny instead of vice-versa. The funny character likely emerged out of ethnic vaudeville, which permitted people to laugh at ethnic stereotypes inside the Irish, Italian, German, Black and Jewish communities.

In Yiddish theater, for example, certain character types emerged, like the “schlemiel” – an inept or incapable person – and the “schlimazel” – who was luckless. As the standard joke goes, the schlemiel is someone who persistently spills his bowl of soup, and it always falls into the waiting lap of the schlimazel. In Yiddish folklore, the entire town of Chelm is composed of schlemiels with expectable consequences. In Yiddish theater, Menashe Skulnik usually played the schlimazel, one of his characteristic songs was, “It shouldn’t happen to a dog, what happened to me.” These character types have not left Jewish-American comedy, even into the Television Age. On Seinfeld, the schlemiel is easy to identify -George Costanza. In Curb Your Enthusiasm, Larry David manages to be both schlemiel and schlimazel.

In Yiddish theater, for example, certain character types emerged, like the “schlemiel” – an inept or incapable person – and the “schlimazel” – who was luckless. As the standard joke goes, the schlemiel is someone who persistently spills his bowl of soup, and it always falls into the waiting lap of the schlimazel. In Yiddish folklore, the entire town of Chelm is composed of schlemiels with expectable consequences. In Yiddish theater, Menashe Skulnik usually played the schlimazel, one of his characteristic songs was, “It shouldn’t happen to a dog, what happened to me.” These character types have not left Jewish-American comedy, even into the Television Age. On Seinfeld, the schlemiel is easy to identify -George Costanza. In Curb Your Enthusiasm, Larry David manages to be both schlemiel and schlimazel.

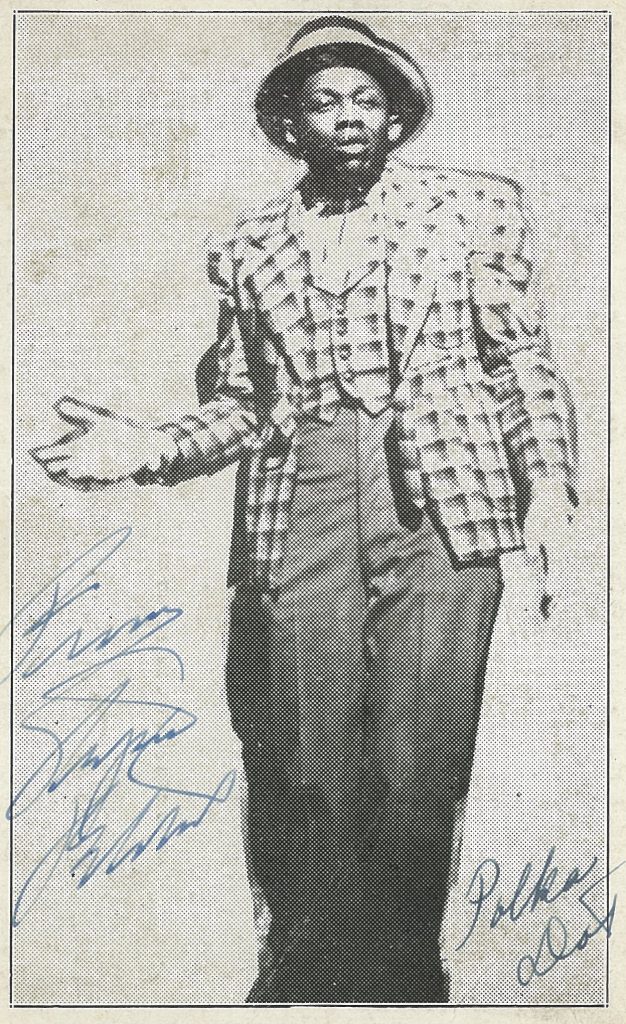

Stepin Fetchit was a comedic performer who emerged from African American ethnic vaudeville and into film in the 1920s by playing “the laziest man in the world.” Was this a negative ethnic stereotype portrayal, as many complained, or was he being an archetypal “trickster” – commonly enacted in polytheistic African and Afro-Caribbean religious expression – who defeats his rivals by playing the inept, bumbling incompetent, as others insisted. Stepin Fetchit took it all to the bank – he was the first Black performer who earned more than a million dollars a year.

In post-World War I New York, vaudeville was withering and being replaced by grand movie palaces that were showcasing the increasingly sophisticated Hollywood productions. By the 1930s as Prohibition was ending, comedians and comedic routines were certainly making it into movies, as the careers of Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Laurel and Hardy, Buster Keaton, W. C. Fields, Mack Sennett and the Our Gang Kids amply demonstrate. Many comedians also brought their acts for a while to the movie palaces, which showcased live performance alongside their films in their early days. Others found refuge in the expanding number of nightclubs that continued some of the ethos of vaudeville – variety acts featured alongside singers, dancers and burlesque.

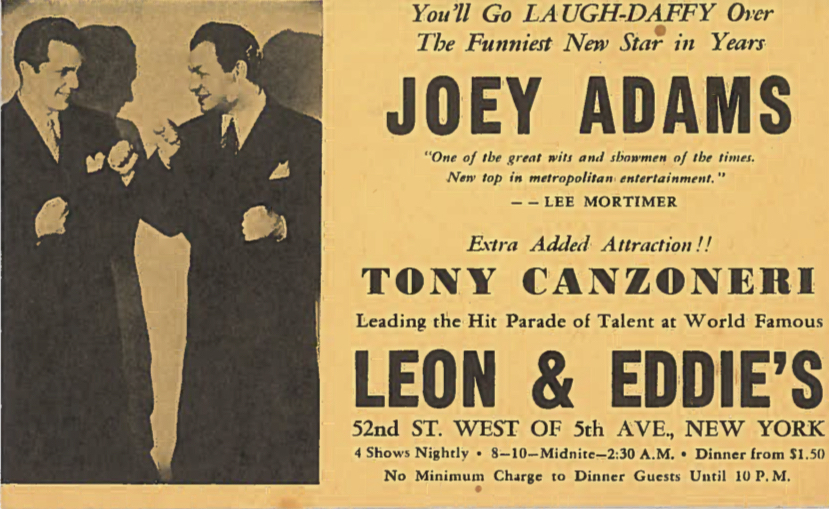

Postcards were there to document these great times of the 30s to the 60s and even into the 1970s. Leon and Eddies, a leading nightclub on 52nd Street promoting itself with copious amounts of postcards, offered top strippers, singers, dancers and comedians. Joey Adams (1911-1999) was a familiar voice from vaudeville and the Borsht Belt. He made it on radio and as a prolific author of funny books. For those keeping score, he was also the husband of long surviving New York Post gossip columnist Cindy Adams.

52nd Street was also the birthplace of “insult” comedy, a contest between the joker and audience to see who could make the other seem more laughable. The 18 Club’s Jack White was the Grandmaster of a style that was later carried on by Don Rickles and Jackie Mason.

Joey Adams was also a headliner for Romanian restaurateur Jack Silverman when he made an uptown move in the ‘50s from the Lower East Side. At the center of this giant postcard for his International Theater Restaurant is “Last of the Red-Hot Mamas” songstress-comedienne Sophie Tucker (1886-1966), a giant of vaudeville – and frequent fixture on the Ed Sullivan Show and other uptown nightclubs – who was known for both her sentimental songs like “My Yiddishe Momme” (My Jewish Mama) and her raw, aggressive sensuality as in “Some of These Days.” Speaking of mothers, another act featured on the postcard are Yiddish superstars The Barry Sisters whose recent hit “Oy Mamme Bin Ich Verliebt” (Oh Mama Am I in Love) had just crossed over from Brooklyn to the Big Time. Also featured at the club is Second Avenue Comic Myron Cohen whose jokes about Garment Center characters were well-loved at that time. Julius La Rosa and Jimmie Rodgers, both of whom had just had recent hits (“Eh, Cumpari” and “Honeycomb”) add some ethnic diversity to the program.

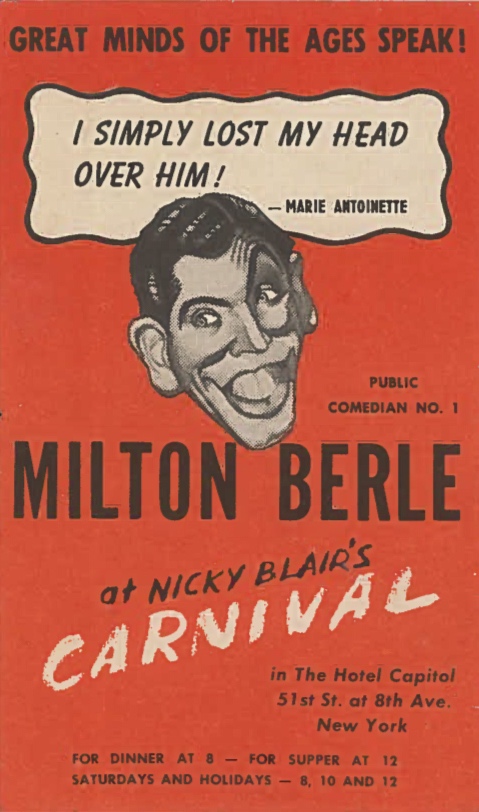

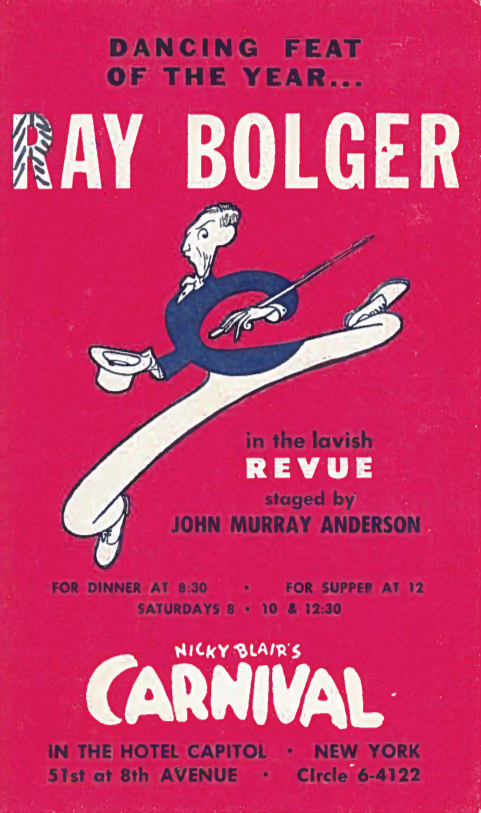

Two 1940s postcards from another Times Square nightclub, Nicky Blair’s Carnival at the Hotel Capitol, feature comics who started in vaudeville and went on to movies and television. Bostonian Ray Bolger (1904-1987) was mostly a dancer, but his rubber-jointed mannerisms made him hilarious. Seeking a brain as the Scarecrow in the 1939 classic film The Wizard of Oz endeared him to everyone and guaranteed a successful career through the early TV era. But no one embraced the new medium as much as Mr. Television himself, Milton Berle (1908-2002.) Beloved by many as “Uncle Miltie” in television’s earliest days, the New York-born comedian went through it all from child actor, vaudevillian, movies and radio to the nightclubs where he became a pioneer of the “standup” style of comedy. Known for doing almost anything to get a laugh, especially cross-dressing, the cigar-loving Berle’s acidic off-stage personality failed to make him many friends and cost him a large share of audience when comedy exploded on 1970s television in shows like “Saturday Night Live.”

Chicago-born Morey Amsterdam (1908-1996) was another Jewish-American performer who started in vaudeville as a foil in his brother’s act and like the others went through movies, nightclubs, radio and ended up in television. He’s probably best remembered for his role as comedy writer Buddy Sorrell on The Dick Van Dyke show. He was a writer at heart and contributed to numerous other comedians and shows when not producing his own material.

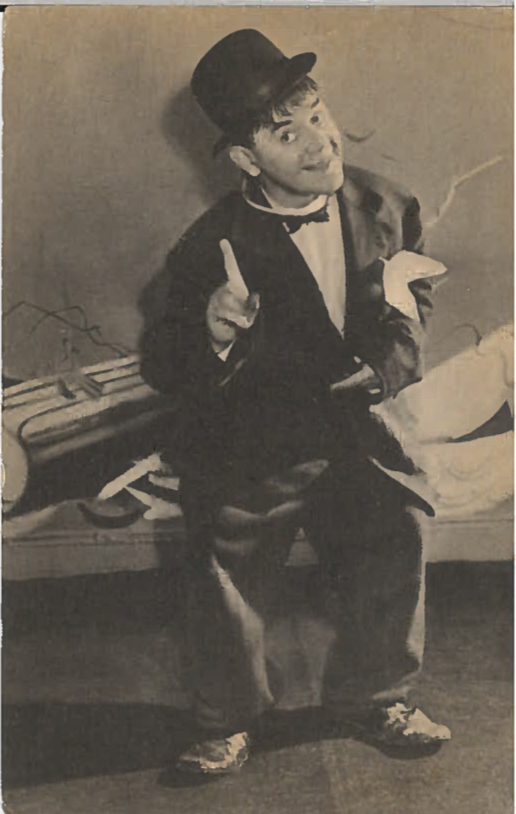

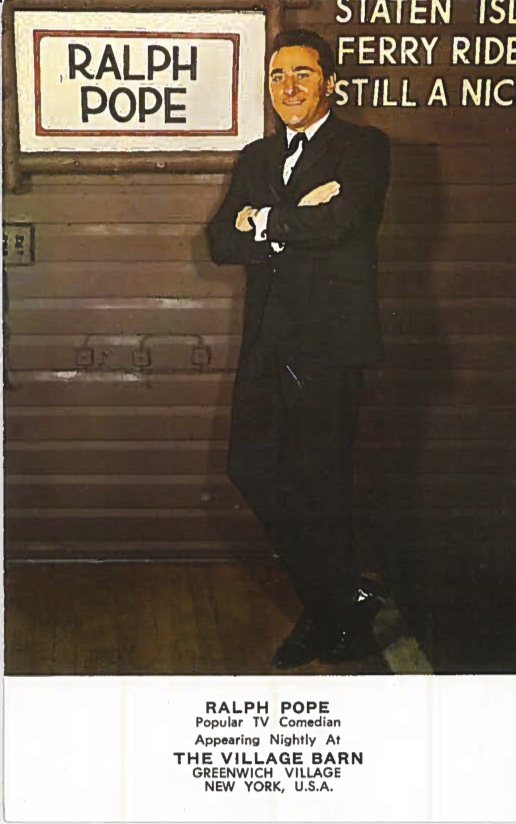

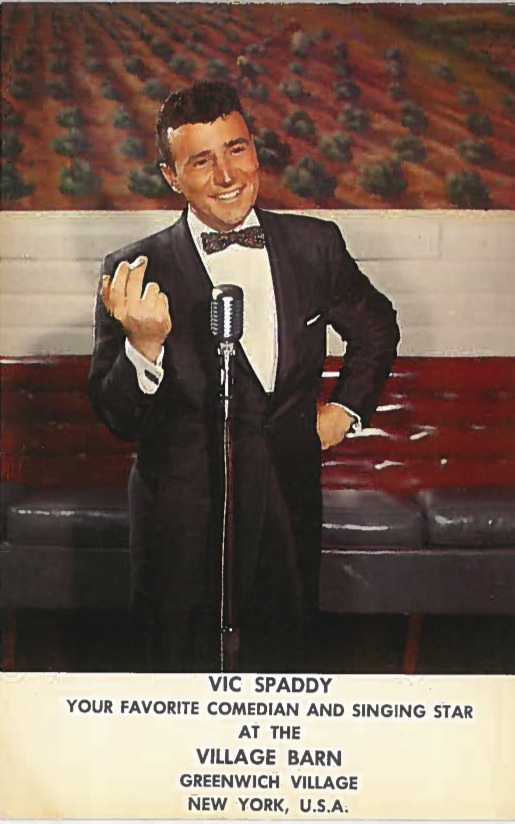

The nightclubs in Lower Manhattan’s Greenwich Village also interspersed comedy with their music and dance programs. Shown below are Jimmy Savo at Café Society, a nightclub committed to healing racial wrongs by thoroughly integrating its performances, its staff and its audience. Prolific postcard publisher The Village Barn introduced many of its comedy acts through attractive chrome cards. The nightclub that tried to be everything to everybody coming to New York for business or fun was influential in introducing the careers of Lou Moscone, Ralph Pope and Vic Spaddy.

Jimmy Savo

Upper East Side nightclub Basin Street East tried to keep jazz alive in the early 60s by sticking with tried-and-true acts from earlier decades but also by riding with Cool Jazz performers like Herbie Mann and Dave Brubeck and picking young up and comers like Barbra Streisand. A young ascending comedian featured on the postcard below is Mort Sahl (1927-2021,) who is credited as the creator of the new “standup” comedy.

Standup was able to keep live performance and the nightclubs alive while most of the funsters had moved on to the movies, like Jerry Lewis, and television “situation comedies” like Lucille Ball, Phil Silvers and Jackie Gleason. Afterwards, into the 1960s and 70s you couldn’t keep people away from their televisions as situation comedies proliferated with “The Odd Couple,” “All in the Family,” and “Sanford and Son.” Comedy shined a bright light on Broadway theater at that time with writers like Neil Simon and Mel Brooks. In 1966, Simon had four hits running on Broadway simultaneously.

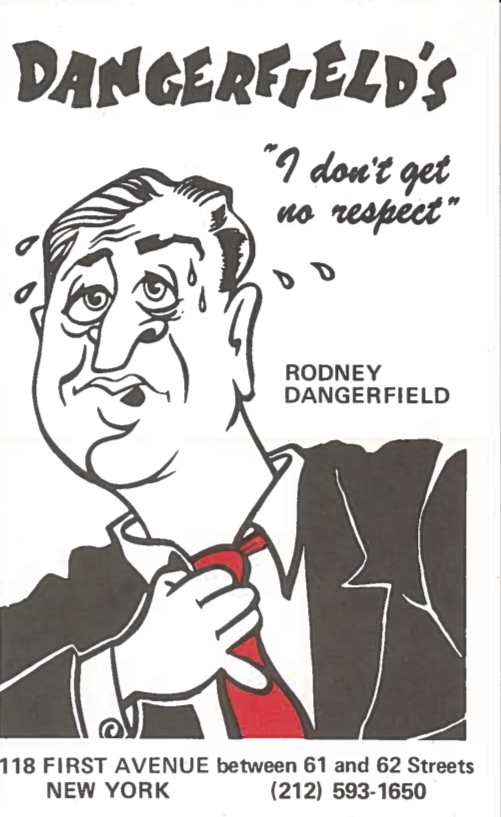

The standup comic was not a jester but a normal everyman pointing out the humor and absurdity in everyday life and political affairs. Improvisational and sharp, Sahl was highly influential – giving us George Carlin, Richard Pryor, Woody Allen, and Lenny Bruce who eventually took the style to tragic depths. Mort Sahl helped to turn San Francisco’s hungry i nightclub into a mecca of standup comedy and inspired the creation of comedy clubs throughout the United States, including the New York showcase for Rodney Dangerfield, whose view of the world was shaped by the lack of respect he received. Sahl went on to become a fixture on late night television and regularly appeared at Bay Area nightclubs to talk about the news until the Covid pandemic kept him at home shortly before he passed on.

Comedy is at a difficult moment right now, battered by the maelstrom of politics, political correctness, racial and ethnic sensitivities and the disappearance of social consensus. Many fear that “comedy is dead.” We all wish we could just go back to laughing at jokes together again, like when Johnny Carson reigned as the avatar of humor on his late-night television show.

Interesting read!

Are all the old time comedians laughing at us now, or crying for us because of the dearth of funny humor on the stage and tube? The Martin and Lewis films were faves of mine as a tween. Eager to watch one recently, I was startled to realize how gross the slapstick was… and how naïve I had been. Stepn Fetchit was another must see playing the handyman on The June and Stu Irwin show. (Seeing an autographed postcard of him was a highlight of this article!) He was funny… then. I am glad to know he prospered, but his… Read more »

A little before my time but a great read nonetheless. Thanks Hy.

A very interesting and good article, but right on about political correctness.

Julius La Rosa is best known for being fired on the air by Arthur Godfrey in 1953.