Hy Mariampolski

Vaudeville and the Vaudevillians

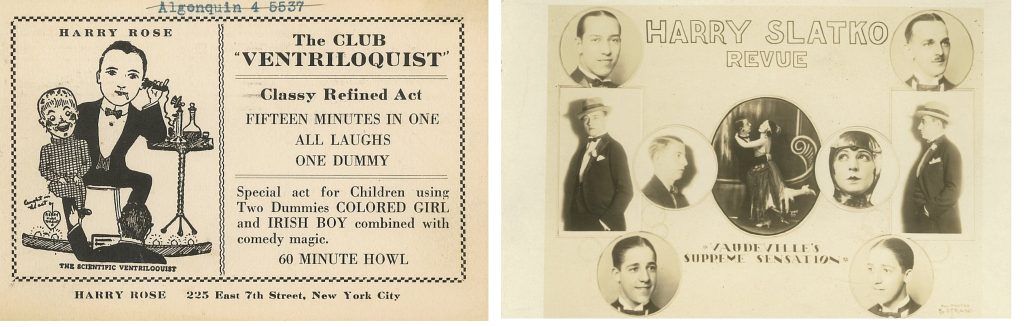

The reigning genre of mass entertainment in New York and the rest of America from about the last quarter of the 19th century through the first quarter of the 20th century was called “vaudeville.” This referred less to a specific art form such as music or dance than to a way of creatively organizing diverse live programs and performances. These might include short plays and skits, comedic routines, singers, musicians and dancers along with acrobats, burlesque-stripteasers, jugglers, ventriloquists and puppeteers, magicians; animal trainers; escape artists and just about anything else that might appeal to audiences.

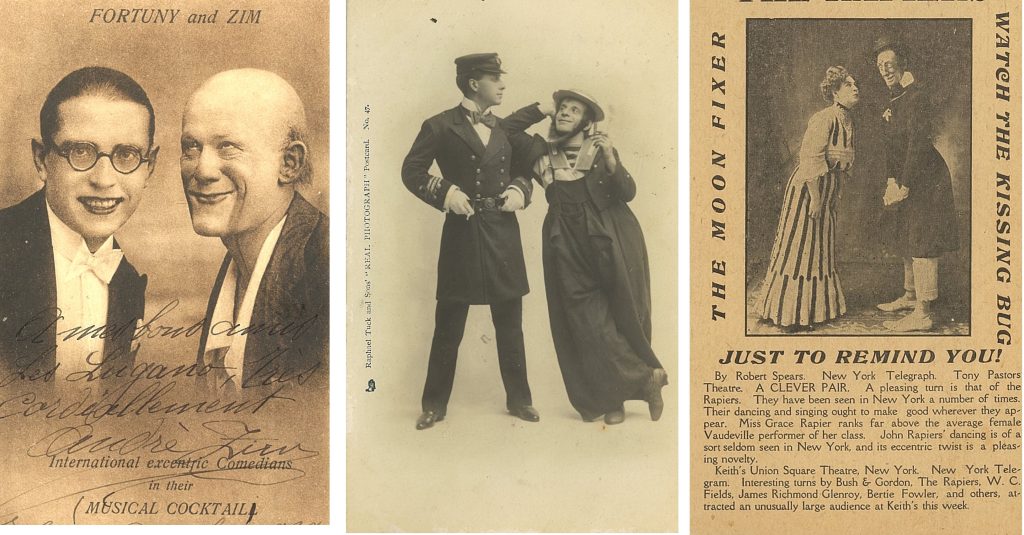

Performers were essentially freelancers recruited by vaudeville agents to perform along circuits or chains of cities, towns and theaters. The acts achieved fame locally at first but then regionally and nationally by turning the best into the stars of the system. Many of these free agents kept their reputations intact after vaudeville’s decline and used their experience as a springboard for roles and careers in movies, both silents and talkies, nightclubs, radio, and television.

Vaudeville was a unique New York creation that arose from the city’s position as the nexus of world-wide transportation and cultural exchange. Various historical factors, such as the Civil War and Spanish-American War as well as notable inventions such as the incandescent light bulb, reinforced New York’s role as the birthplace and leading exhibitor of many forms of entertainment and nightlife.

Starting out in the brash and boisterous concert saloons of the Bowery and Lower Broadway, moving through dime circuses like the one run by P. T. Barnum on Park Row, using content drawn from blackface minstrelsy and plantation hijinks from the deep South, enriched by ethnic theaters, sometimes fueled by alcohol or class resentments, nostalgia for a home that no longer existed, that never existed, New York’s nightlife culture was forced to appeal to everyone simultaneously. The entertainment had to engage members of all New York’s ethnic groups and social classes; women and families as well as men. Vaudeville had to be virtuous and vitriolic at the same time, adept at buffoonery and burlesque, cynical, sarcastic and suggestive, vaudeville was an art form made for New  York.

York.

Tony Pastor’s reputedly the first, was able to create this synthesis and bring the art form to 14th Street and the Union Square area and this is where the intersection of vaudeville and postcards began. Located in the basement of Tammany Hall, Democratic party headquarters, enabled Pastor’s to be seen as respectable, prosperous, and politically protected. Pastor was notably adept at merging the respectability and restraint of institutions like the Germania Theatre, just a few blocks away, with the Bowery entertainment culture known for its indulgence and insobriety.

The primary ingredient for assuring the success of the vaudeville enterprise was organizational – in a day and age long before computers. Somebody had to take literally thousands of individual acts, highly differentiated, each full of ego and bravado and organize them in a rational manner for each of dozens, if not hundreds of individual vaudeville theaters. Theaters were organized along circuits that were constantly changing as new theaters were built conforming to growth in population and expansion of transportation lines.

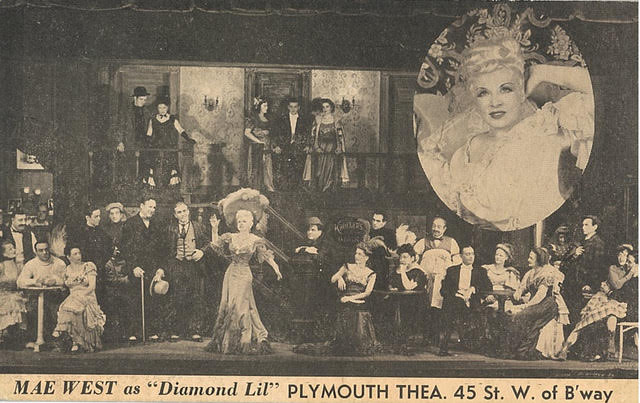

The audience was looking for variety entertainment but was also seeking  something formulaic because they were honoring the emerging star system. High quality acts distinguished themselves very quickly and the crowds demanded to see the standouts like Sophie Tucker, Eddie Cantor, Mae West, and the Marx Brothers.

something formulaic because they were honoring the emerging star system. High quality acts distinguished themselves very quickly and the crowds demanded to see the standouts like Sophie Tucker, Eddie Cantor, Mae West, and the Marx Brothers.

The B. F. Keith organization was first out to use its internal network of agents to create programs and then circuits. E. F. Albee was a competitor soon absorbed into the business. With few barriers to entry, many more booking companies came along by holding on to their own geographies. Names like Orpheum, Loew’s, Fox, Pantages and others became popular. However, The Palace and Hammerstein’s Victoria in Times Square and B. F. Keith’s Union Square Theater had the stars everyone wanted to see.

A variant form called “vaudeville,” the Kinetoscope, using personal viewers which relied upon a continuous feed of audience one-cent coins to keep the entertainment going was tried at Union Square but was not successful.

In New York, the heartland of vaudeville, the expedient was to push theaters into the boroughs and the larger region by bringing variety entertainment nuanced for every ethnic group, social class and political persuasion right to where the people lived. The postcards below show the impact of this theater-building movement across the City’s neighborhoods: in Upper Manhattan, the Bronx, Downtown Brooklyn, Williamsburg, Brighton Beach, and Queens.

Attempts were made to unionize the entertainment workers to act as a countervailing force against the vaudeville agents – the pro-union workers called themselves the “White Rats.” Despite their colorful name, their organizing efforts were unsuccessful, and the union devolved into a service organization called the National Vaudeville Artists, Inc. The organization offered diverse club house amenities for visiting vaudevillians, such as sleeping, dining, lounges, and billiard rooms.

Commenters and social historians of popular culture often note the intense rapport that existed between the vaudevillians and their audiences. The performers did not exist in a separate plane, commenting as external judges, but related organically to their audience, with solidarity, embodying their struggles and aspirations and being at one with them.

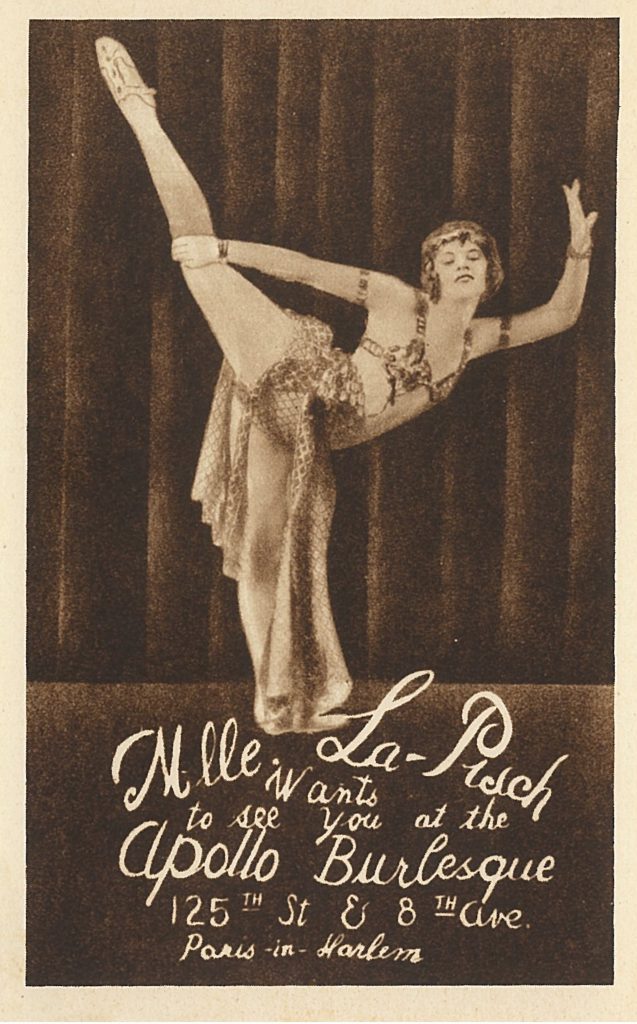

For the entire half-century that vaudeville served as America’s major form of theatrical diversion, it was under constant challenge to maintain its cutting edge as social commentary and comedic performance. At the same time, it was uniquely required to maintain its “respectability” as family entertainment. As America was shifting from the strict Victorianism of the late 19th century to the looser mores that characterized the 20th century, there was constant fear of breaking boundaries. To some extent this fear was encapsulated in the “sensual” dimension. Burlesque distinguished itself from vaudeville by its emphasis on erotic performance and increasingly became limited to its own range of theaters. After the turn of the century and again in the 1930s, restraint of sensuality became the order of the day, contributing to the decline of burlesque.

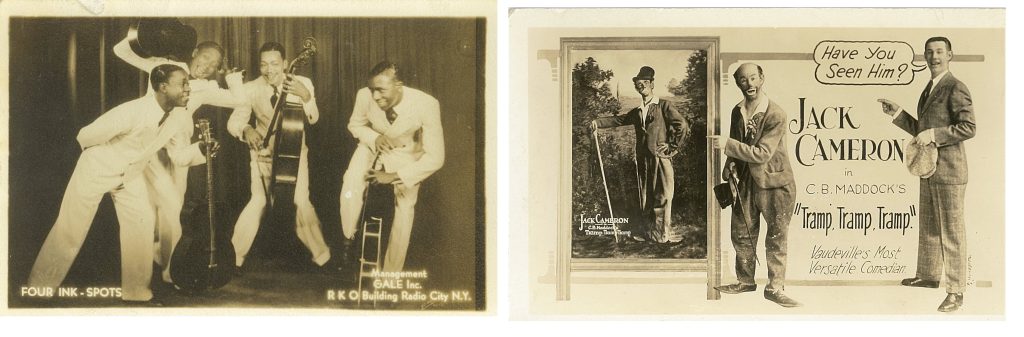

The other standard that shifted as vaudeville changed over time was the ethnic dimension. Early vaudeville was unrestrained about trading in ethnic stereotypes, no matter how uncomplimentary they were. Speaking in unintelligible Irish, German, Italian or Yiddish accents contributed to the general hilarity. Blacks were portrayed in blackface by white performers, even blacks appeared in blackface. 19th century Southern plantation stereotypes were an essential feature of vaudeville song, dance and comedic routines. When African Americans and Caribbeans began moving to the northern United States at around the time of the First World War, a new consciousness developed that challenged the stereotypes and discriminatory treatment of Black Americans. Nevertheless, it took many years of the Civil Rights struggle for tangible liberties to be achieved.

Well, what “killed” vaudeville? That’s a very hard question to answer. It’s never really been proven that vaudeville ever died. Every entertainment form that came afterwards was influenced by vaudeville and the vaudevillians were absorbed into the larger American entertainment culture as new technologies and tastes were created. First, there was the evolution of “legitimate theater” divided into opera, drama, and musical theater. Opera and drama were clearly influenced by the emotional rapport of vaudeville. Musical theatre as it developed in 20th century New York owed a great deal to vaudeville under the leadership of people like George M. Cohan, Victor Herbert, Florenz Ziegfeld, Jerome Kern, George and Ira Gershwin, Richard Rogers and Lorenz Hart and Oscar Hammerstein, grandson of the owner of Hammerstein’s Victoria and others.

Mae West was an actress in high demand for early musical comedies

Then, there were the movies. In the early stages, vaudeville began absorbing a high proportion of filmed entertainment and many vaudevillians were lured directly into the movies – the Marx Brothers, W. C. Fields, Bob Hope, and many more. The next stage of ascendancy involved the creation of grand movie palaces built to accommodate epic filmed productions of the era. Live entertainment remained connected to the evolution of movie palaces, continuing in some theaters as late as the 1940s.

Eddie Cantor shows up for the Tom Breneman

Breakfast in Hollywood radio program

Vaudeville had a direct influence upon the nightclub and cabaret scene of the 1920s to the 1950s, particularly in comedy clubs. Finally, early radio and television depended upon vaudeville for its content and ethos. Variety TV programs like the Ed Sullivan Show and Late Night with Johnny Carson and David Letterman were direct successors.

Vaudeville never died. It just grew an antenna and moved forward.

* * *

Postscript: Postcards and Vaudeville

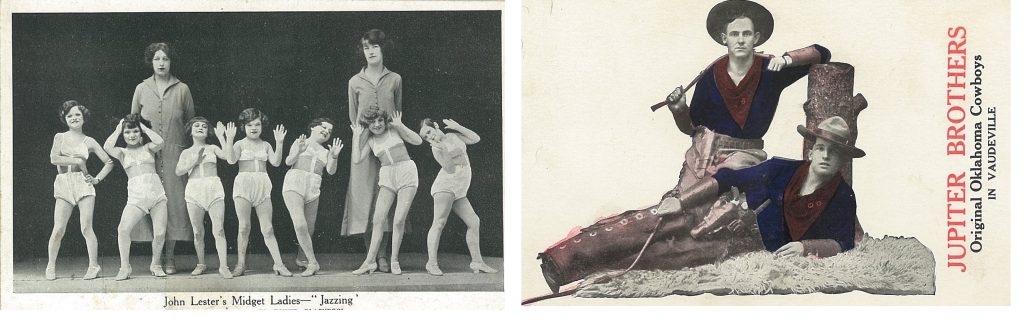

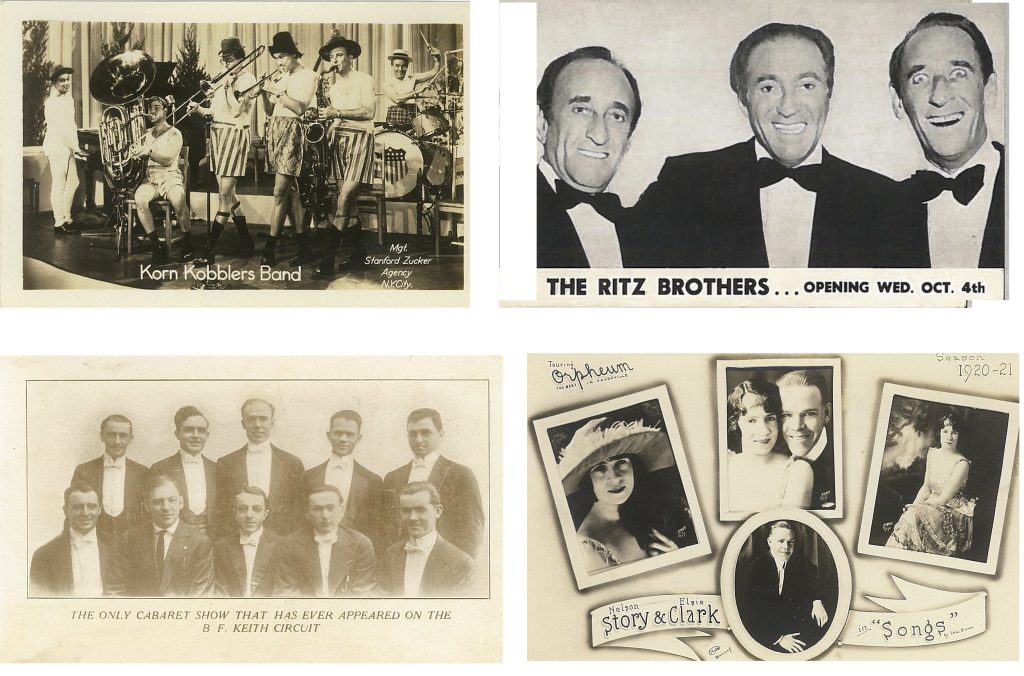

Since the postcard craze coincided with the heart of the vaudeville era, hundreds, probably thousands of picture postcards were published by vaudevillians to promote their acts. The cards have a vivid and unvarnished quality that make them endearing to lovers of vernacular arts. Many of these use the “real photo” medium for publication giving them an extra boost of realism.

After vaudeville’s decline, many performers continued to use postcards to promote their acts in nightclubs, radio and films.

Using these promotional postcards for vaudeville acts, we’ve tried to simulate the charm, bravura, and contrasts that characterized the vaudeville experience. Imagine how much fun it must have been to sit in a Keith’s or an Albee’s and watch a sequence of acts like these.

Another great article, thanks Hi

Thanks for opening another window into old New York Hy. Keep-um coming!

Another good story well told. Thanks Hy! I’d hoped there would have been a mention of my late wife’s recently discovered grandfather.

It never ceases to amaze me just how many people appear to have been making their living this way, in these mostly obscure and forgotten acts – leaving no mark on history other than a mention or two in old newspapers. I guess there were some great stories for the grandchildren in the 50s and 60s.

So many super hard to find cards….wowwwwwwwwwwwwwwww.