Hy Mariampolski

New York’s Movie Palaces

There was a time in New York City when people went out to palaces to watch movies instead of peering at shrunken versions of films on their smartphones. The nation’s top architects contended for commissions to design theaters in the Neoclassic, Baroque or Renaissance style. They reached to religious architecture, history and fantasy for creations in the Moorish, Romanesque and Aztec style. The movies in the 1920s to 1940s became an indulgence and a retreat for middle-class Americans and the empresarios offered them in an environment that matched their aspirations.

In large part, the evolution of movie theaters paralleled the development of movies and their underlying technologies and shifts in the theater arts and the social meaning of filmed entertainment – from shorts shown in Nickelodeons to serious grand features. There were also numerous creative entrepreneurs with a vision that crafted concepts into concrete, people like theater-builder Marcus Loew, architect Thomas Lamb and master showman Samuel ‘Roxy’ Rothapfel and most of the advancements and failures happened in New York City. Postcards of the era documented and promoted their achievements. They deserve careful analysis as artifacts of the social history of an art form.

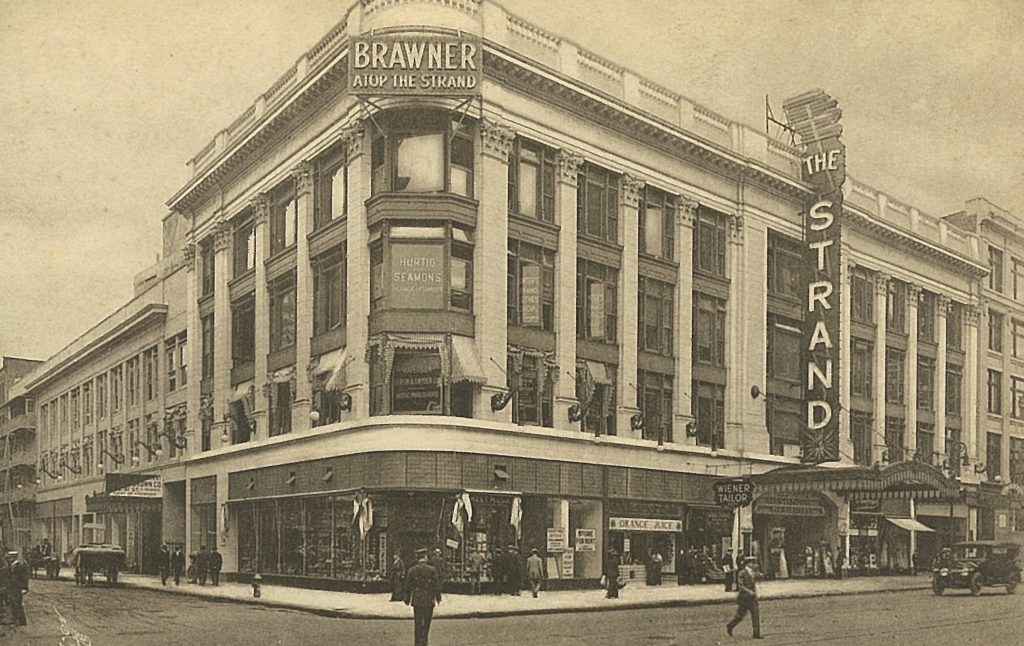

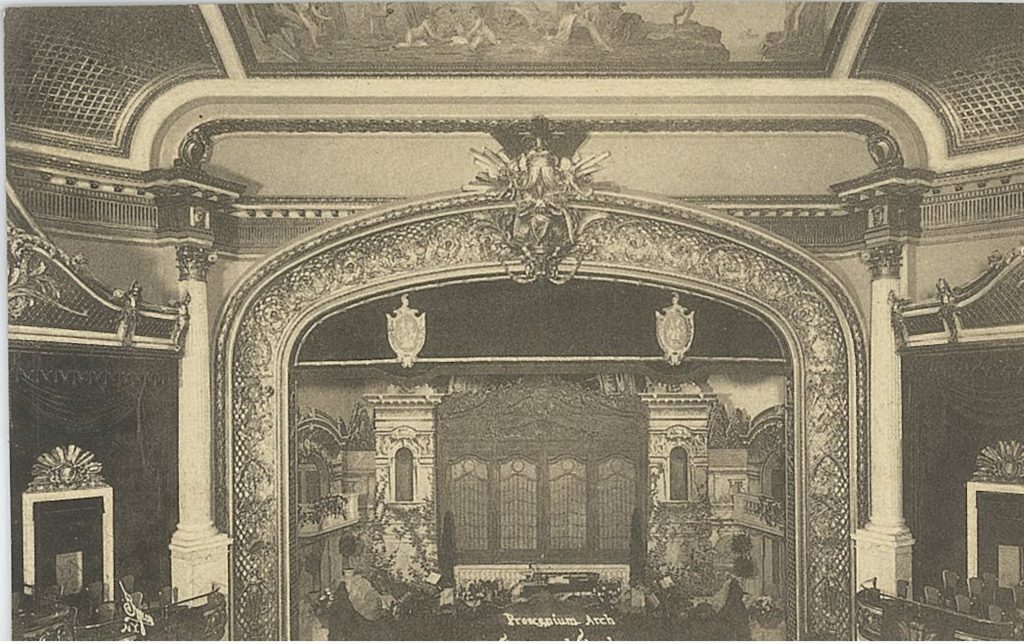

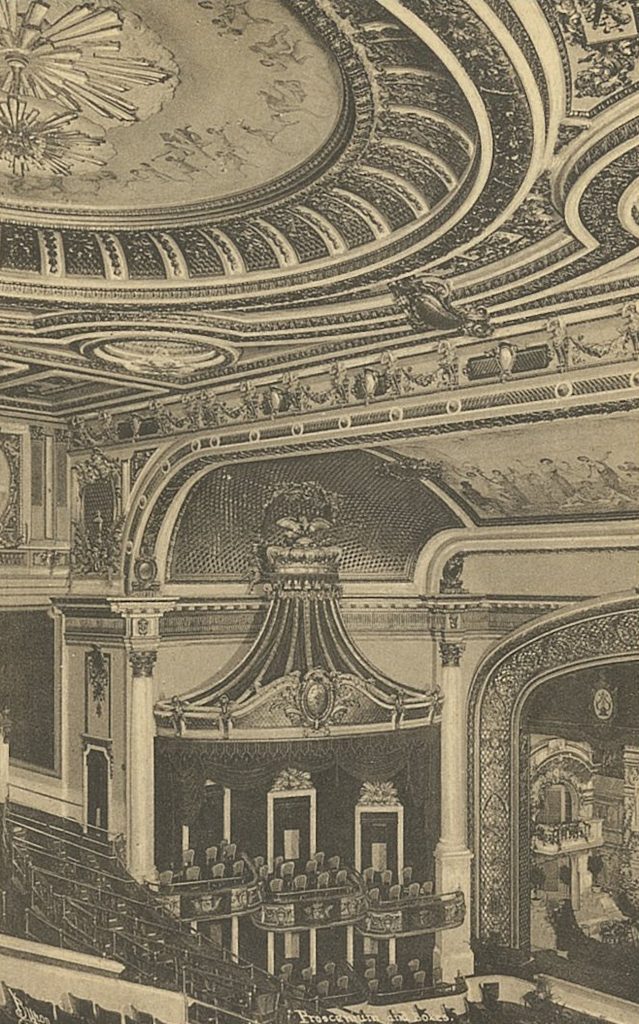

The Strand Theatre, a movie palace located at Broadway and 47th Street was arguably the first one out of the gate, built in 1914 at a cost of a million dollars. Designed by Thomas Lamb with a program managed by Samuel “Roxy” Rothapfel who created the luxurious style of movie presentation, the Strand showed films primarily made by Paramount Studios until just about the end of the 1920s. This coincided with the “Silent” era of motion pictures.

The silents were not by any means silent. They simply lacked the technology for dynamic recording of dialog alongside the visual recording. Actors in the silent era were challenged to broaden their character development and communication through makeup, pantomime and body language, particularly through their eyes and hands. Lon Chaney’s (1883-1930) iconic roles in the films The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and Phantom of the Opera (1925) represent the epitome of emotionally expressive performance. The silents also presented dramatically linked musical scores which, in most cases, were improvisational and relied upon just a piano or organ keyboard. As the top films endeavored to distinguish themselves, they increasingly used specially created orchestral scores.

Movie palaces boasted orchestras and their conductors achieved a certain level of fame. In their early stages the programs at movie palaces were not entirely detached from vaudeville – their films were shown alongside musical and variety acts. In some cases, this mix of live and filmed entertainment persisted over the long run, as for example at Radio City Music Hall where the Rockettes and the Corps de Ballet kept their places on the program.

Movie Palaces were generally devoted to a grand scale in their audience capacity and in outsized foyers and promenades decorated with massive chandeliers and wall ornamentation. The concept was well adapted to moving quickly beyond New York City to rapidly expanding population centers in the West, Southwest and Pacific Coast. Many of the movie palace buildings constructed through this era have survived albeit in highly modified forms, for example as multiplex cinemas, performing arts centers, and theatrical museums.

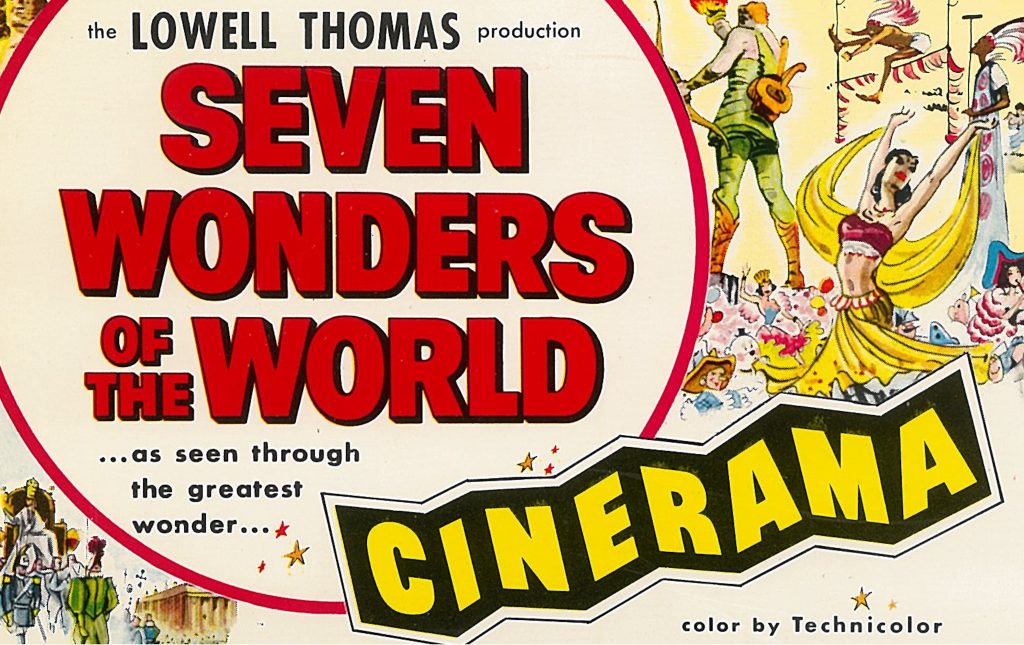

The Strand Theatre switched to Warner Bros. as their source for new products when the “talkies” emerged and became known as the “Warner Strand” and just the “Warner” in 1951. Movie producers became increasingly challenged by the loss of audiences during the Postwar era as consumers were lured away by television and suburban living. Hollywood’s first reaction was to expand their offer into “wide-screen” presentations. Creating a more immersive experience and a near 3-dimensional illusion, the Warner Bros. wide-screen product was branded as “Cinerama” and the Warner Theatre became New York’s outpost for this technology from the 1950s and into the 1960s.

No doubt the most successful and memorable film of the Cinerama era at the Warner was It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World the 1963 madcap comedy that featured three generations of comedians, some of whom like Milton Berle, Phil Silvers, Sid Caesar and Imogene Coca had already scored massive hits as TV stars. They appeared in this howler alongside such veterans of vaudeville and the silents like Buster Keaton, ZaSu Pitts, and Jimmy Durante as well as young up and comers like Buddy Hackett and Dick Shawn. The film showcased more than 50 top jokesters all together.

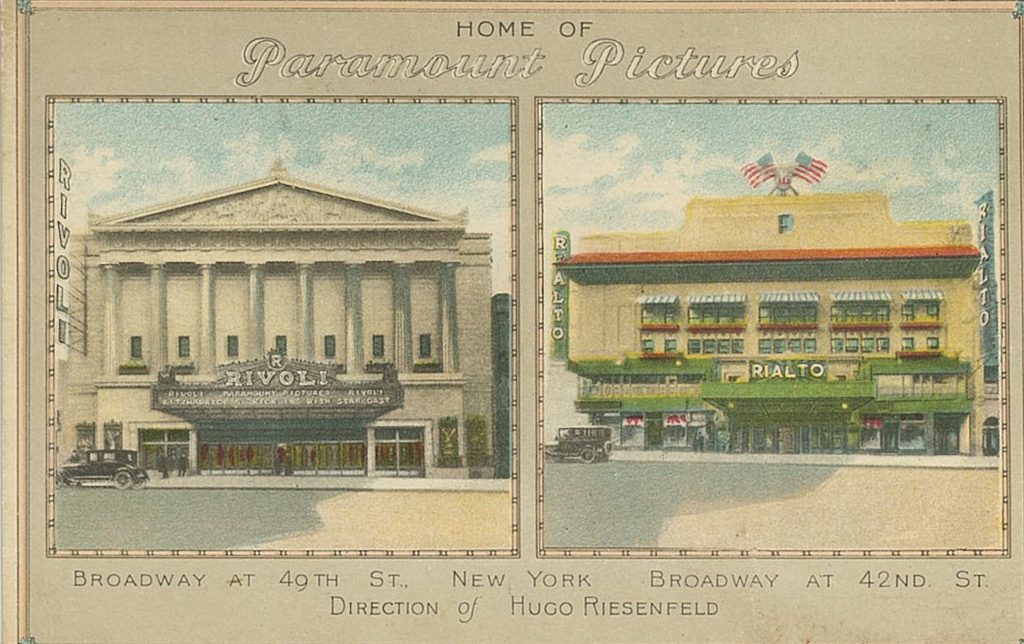

The Rialto and the Rivoli were “sister” movie palaces managed by Paramount/Famous Players in Times Square and are emblematic of the life histories experienced by this theatrical form in New York. The 1,960 seat Rialto built at the corner of Seventh Avenue and 42nd Street replaced Oscar Hammerstein’s vaudeville venue the Victoria in 1916. Together with the Strand, they defined the newly emerged movie palace trend. Designed by Thomas W. Lamb and Rosario Candela and with a program managed by “Roxy” Rothapfel, the Rialto theater opened with Douglas Fairbanks in “The Good Bad-Man” and Roscoe (Fatty) Arbuckle in “The Other Man.” Arbuckle was the protagonist of Hollywood’s first great sex and death scandal when he was accused and tried for the rape and murder of starlet Virginia Rappe at San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel in 1921.

With five shows daily, the venue featured the orchestra and several vocal and instrumental solo acts. Films were accompanied by the theater’s grand organ.

The movie palace was shuttered in 1935 and replaced by a smaller 700-seat Art Deco styled Rialto along with shops and offices. By the 1970s, the theater had deteriorated into a porn house, however an attempt was made to recreate it as a legitimate theater in the 1980s and turn some of the building’s space into a television studio which was used by the Geraldo Rivera and Montel Williams programs. The building was torn down in 1998 and replaced by an office tower.

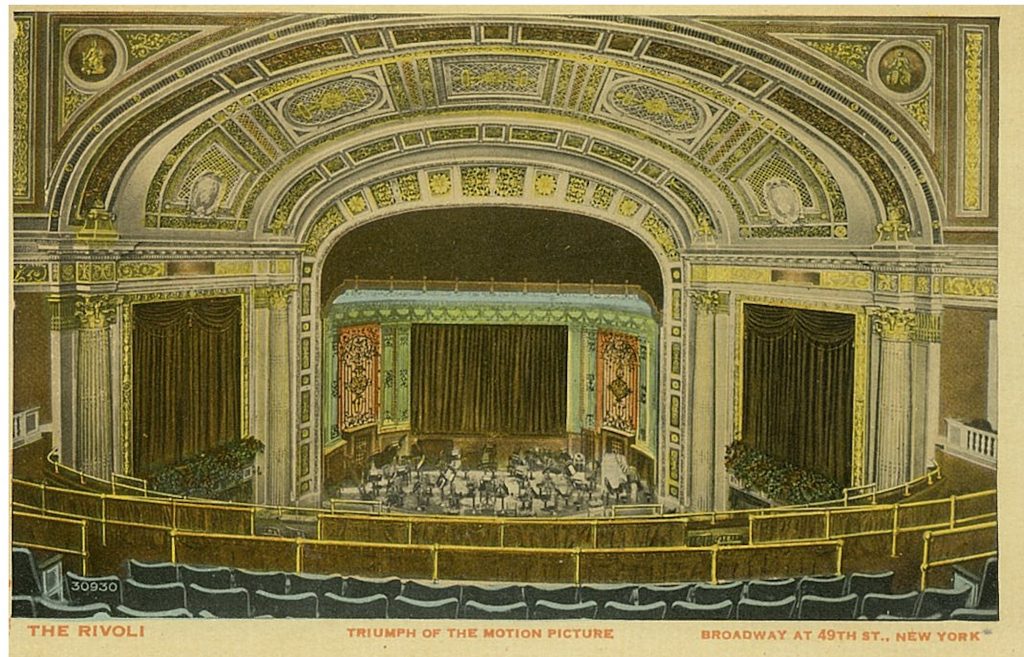

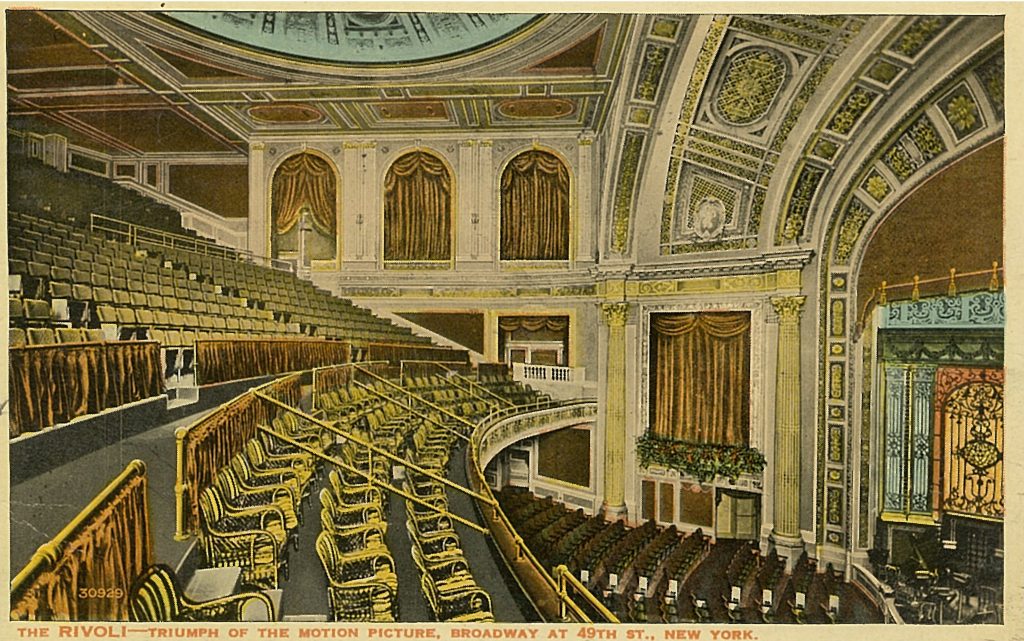

Another lost New York treasure designed by master theater architect Thomas W. Lamb, the 2,270-seat Rivoli Theatre opened December 28, 1917, with Douglas Fairbanks in “A Modern Musketeer.” Located at the north end of Times Square on Broadway between 49th and 50th Streets, the Rivoli was known for its Greek Revival design. The program there also was created by S. L. “Roxy” Rothapfel who determined that musical sophistication was essential to the success of movie palaces. Consequently, the Rivoli showcased Dr. Hugo Riesenfeld’s fifty-piece orchestra, plus a once-a-week performance by the combined orchestras of the Rialto and Rivoli, called the Rothapfel Symphony Orchestra.

By the 1950s, the Rivoli was known as a successful “roadshow” house for its sustained showings of top feature films. It converted to a gigantic, curved screen to accommodate the wide-screen offerings in 70mm Todd-AO, an alternative to Cinerama developed by producer Michael Todd. For those keeping score, Todd was the third husband of female superstar Elizabeth Taylor, and she was his third wife. The best man at their Acapulco wedding was Mike’s best friend, Eddie Fisher, along with Mexican comedian Cantinflas. Fisher ran off with Taylor when Todd was tragically killed in a crash of his private plane in 1958, deserting his wife singer Debbie Reynolds. During the filming of the epic feature film Cleopatra, its star Elizabeth Taylor ran off with her co-star and fifth husband Richard Burton, abandoning Eddie Fisher.

Mike Todd’s Academy Award winning best picture Around the World in 80 Days played at the Rivoli for 103 weeks starting on October 17, 1956. Other blockbusters that premiered here included West Side Story opened October 18, 1961, and screened for 77 weeks, and Cleopatra – June 12, 1963, and shown for 64 weeks. Other films that opened here for successful long runs included The Sound of Music, The Sand Pebbles, Hello Dolly, Fiddler on the Roof, and Man of La Mancha. To promote the run of Cleopatra, the theater’s iconic Greek Revival façade was shaved and replaced with something looking vaguely Egyptian Revival. In 1981, the wide screen was ditched, and the theater divided in two as the United Artists Twin. This identity lasted until 1987 when the theater was demolished and replaced by a black glass skyscraper.

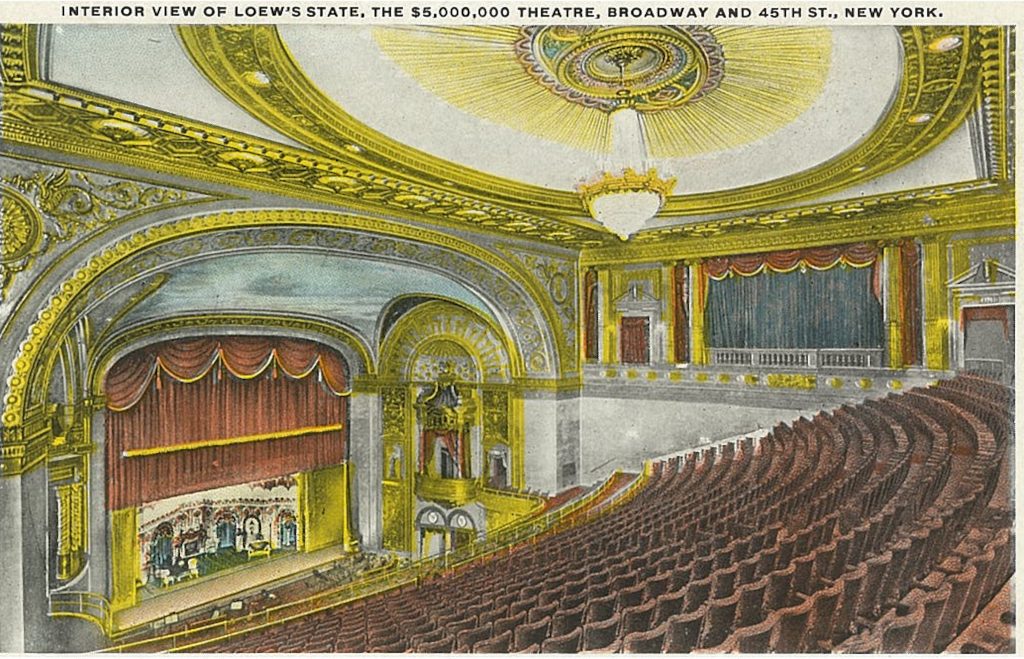

Designed by master architect Thomas Lamb in the Adam style as part of a 16-story office building for the Loew’s Theaters Company, the 3200-seat Loew’s State was one of three important theaters built in Times Square by Marcus Loew. Starting in 1904, the entrepreneur had taken the exhibition business through the Nickelodeon stage, in which short films were shown in specially adapted neighborhood stores, and into the vaudeville era, during which theaters were used to show collections of independent live acts sometimes supplemented by filmed entertainment. The 1921 opening of the Loew’s State at 1540 Broadway and 45th Street was Marcus Loew’s opportunity to advance to the industry’s next level by creating a movie palace committed to showing Hollywood’s increasingly serious films. Loew also purchased and consolidated three individual studios to create MGM, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, to produce the creative filmed content that would support his theaters.

The Loew’s State was known for loyally holding on to vaudeville acts while eventually showing second runs of movies, that is, not premieres but films that had already gained an audience and were there to appeal to those who has missed it the first time. Vaudeville definitively vanished from this venue in 1947, after which the State began to compete for the premieres and first runs, like Annie Get Your Gun (1950), Ben-Hur (1959), and Becket (1964), while hopping on the wide-screen trend with CinemaScope and VistaVision. A 1959 redesign of the theater cut the number of seats nearly in half and made them more commodious. The Loew’s State reopened with the New York premiere of the sexy stunner Some Like It Hot with its star Marilyn Monroe in attendance.

The State succumbed to the multiplex style, splitting in two in 1958 and as a final hurrah staged the premiere of The Godfather in 1972. It was mostly downhill from there. Closed by developer Bruce Eichner in 1987, it was replaced by a 44-story office tower originally known as the Bertelsmann Building after the German publisher but is today known just by its address 1540 Broadway.

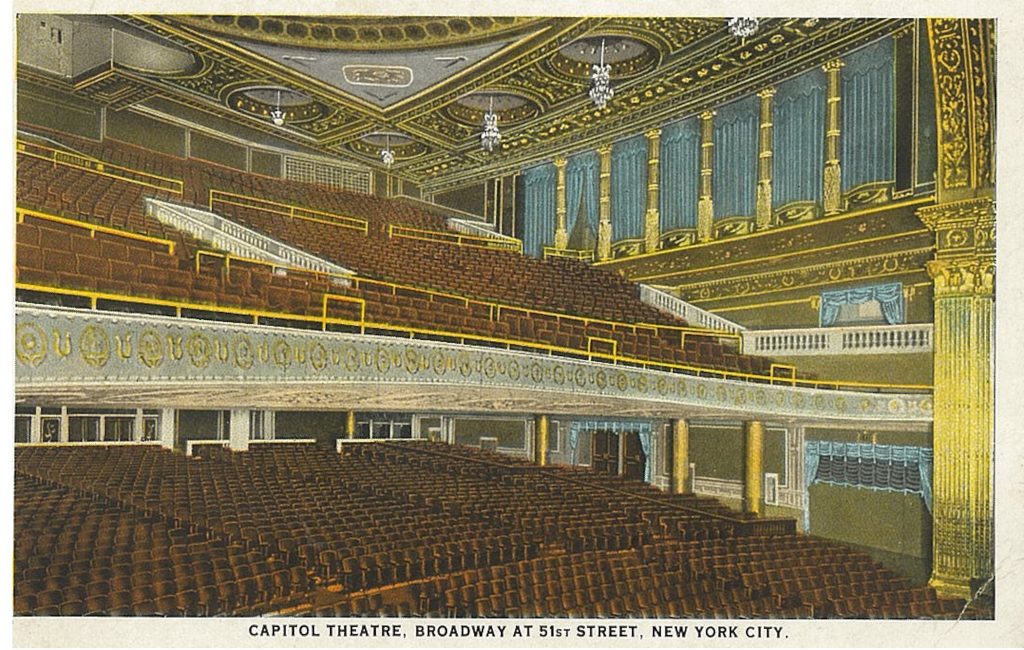

The Capitol Theatre was built in 1919 at 1645 Broadway at 51st Street just north of Times Square. Designed by Thomas W. Lamb with 5,200 seats, the Capitol was purchased by Marcus Loew in 1924 with the intention to make it the flagship of his expanding theater empire. Showing premieres and first runs of MGM films alongside the Astor Theater and the Loew’s State, the Capitol was also known for live musical revues and jazz and swing performances, which gave the theater an important presence on the radio.

Throughout the golden age of movies, MGM was known for matching its audience’s aspirational needs for glamor and sophistication. Consequently, the studio put many of the industry’s A-list superstars – Greta Garbo, John Gilbert, Joan Crawford, Lon Chaney, Buster Keaton, Clark Gable, Jean Harlow, Spencer Tracy, and many more – and creative directors, like King Vidor and Erich von Stroheim, on long term contracts, often luring them away from competitors. MGM was always known for musicals and “series” films, which after the 1960s included James Bond. The studio was also devoted to intense production quantity along with quality which kept people working and audiences cheering despite economic crises and dislocations. Loew’s theaters are where they came to see King Vidor’s 1925 World War I classic The Big Parade and the 1939 romantic comedy by Ernst Lubitsch Ninotchka starring Greta Garbo and Melvyn Douglas. 1939 must have been a fabulous year for movie goers with the premieres of both The Wizard of Oz and Gone with The Wind.

The Loew’s Capitol was retro fitted for Cinerama wide screen showings in 1964 and its last engagement was the 1968 MGM classic 2001: A Space Odyssey. An all-star benefit hosted by Bob Hope and Johnny Carson celebrated the theater’s closing on September 19, 1968. It was replaced by the 48-story Uris Building, today known as Paramount Plaza.

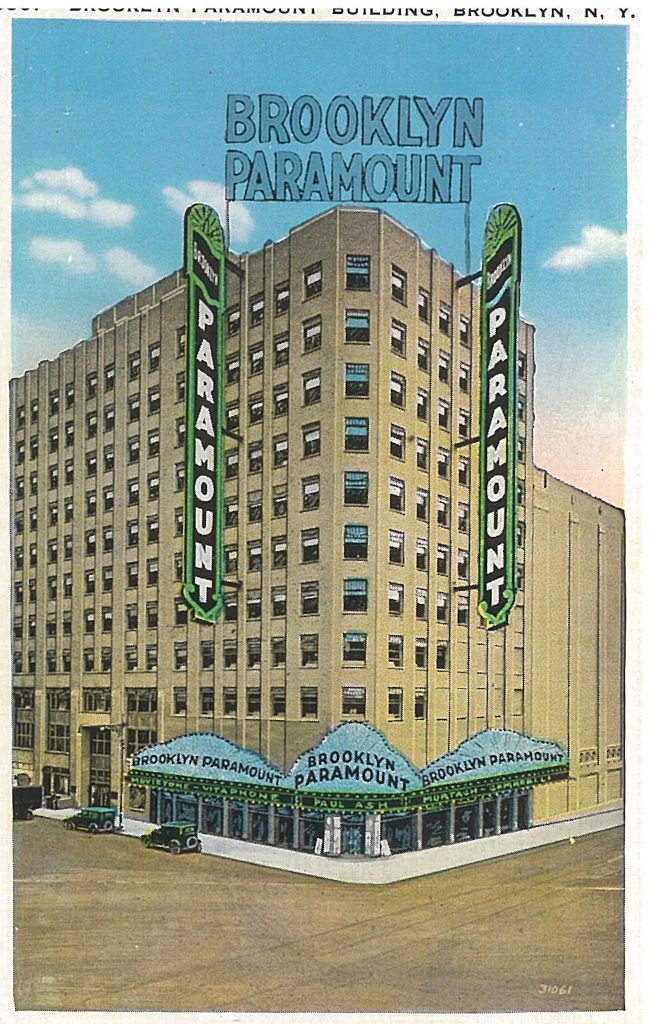

The Paramount Theatre was a 3,664-seat movie palace built into the Paramount Building located at Broadway and 43rd Street in the heart of Times Square. Designed in 1926 by Rapp & Rapp, the building continues to serve as the parent company’s headquarters. It was a showcase theater for Paramount productions but eventually became better known for live musical presentations hosting leading bands and soloists from the 1930s through the ‘50s. Everyone from Benny Goodman, the Andrews Sisters, Glenn Miller all the way over to Perry Como, Frank Sinatra and even Buddy Holly mounted memorable events here. Along with its sister Paramount Theater in Brooklyn, it featured early rock’n’roll shows produced by pioneer disc jockey Alan Freed. The New York Paramount was the site of the world premier for Elvis Presley’s first movie Love Me Tender.

Time was not kind to the theater and its impressive interior built to resemble the Paris Opera. Starting in 1964, its interior and marquee were trashed. Its notable Wurlitzer organ was shipped off to the Wichita Kansas Convention Center where it is still in use. After many years as extra office space for the New York Times, it came back after the millennium as an event and restaurant space and today is home to the Hard Rock Café. Continuing its long tradition as a theater district icon, the giant clock at the Paramount Building chimes every day at 1:45 and 7:45 to alert theatergoers that only 15 minutes remain until curtain time.

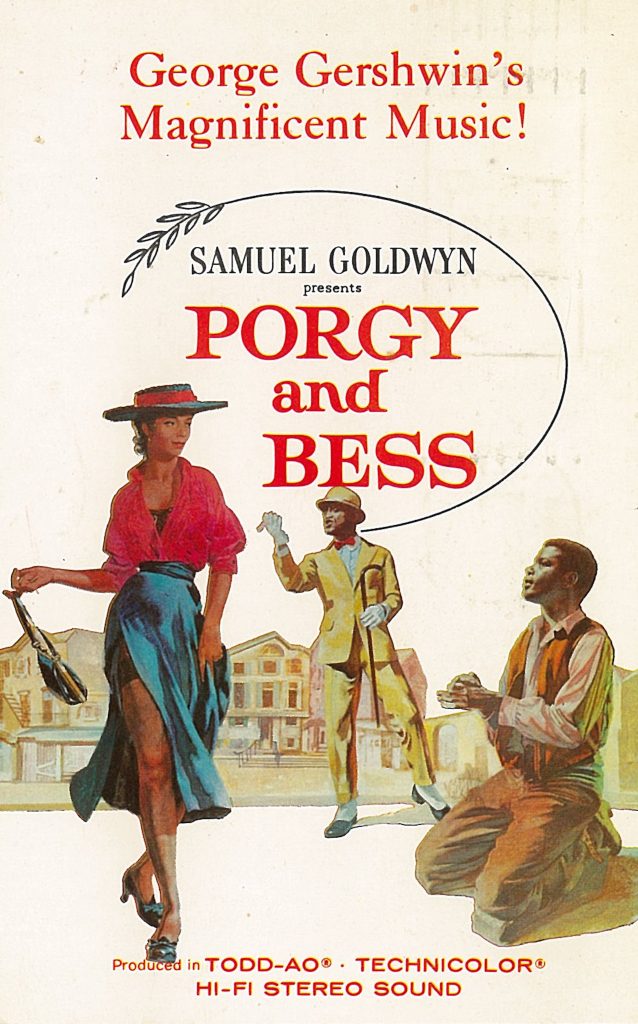

When the new wide-screen and enhanced sound technologies became the standard for films in the 1950s, several theaters issued postcard promotions to connect their current offerings to these advancements. The filmed version of George Gershwin’s masterpiece Porgy and Bess was touted as being presented in Todd-AO, Technicolor and Hi-Fi Stereo. Windjammer, playing at the Roxy was presented in the “exciting new Cinemiracle Process,” as its postcard boasted.

Like the vaudeville theater concept, the movie palace style was pushed out into New York City’s boroughs and metropolitan area, before going national in the late 1920s and early ‘30s. Their films were a source of succor and support during the Depression and World War II years, however, as neighborhood demographics, tastes in filmed entertainment and the economics of movie houses shifted in the postwar era, the movie palaces were largely abandoned and left to deteriorate. The only ones that pulled through with some preservation of architectural integrity, apparently, were those that were turned into churches or were successfully revived as concert and events spaces.

Today the Kings Theatre once again presides over Brooklyn’s Flatbush Avenue. Designed in 1929 as one of five “Wonder Palaces” in the New York Metro by Rapp and Rapp with interior elements borrowed from the Palace at Versailles and the Paris Opera, the 3,676-seat house closed in 1977. It sat forlornly for many years until redeemed by a 2015 renovation as a concert venue. The fate of the RKO Keith Theatre in Flushing, Queens was not as fortunate. Originally built as a vaudeville house but designed in the movie palace style by Thomas W. Lamb in 1928, the 2,974-seat theater was especially known for its Spanish Baroque Revival lobby and interior amenities. Despite valiant efforts by preservationists, it appears this landmark is about to be rebuilt as a condominium.

In contrast, the Loew’s Valencia Theatre, another one of the Wonder Palaces on Jamaica Avenue in Queens, has preserved its Spanish Colonial and Pre-Columbian façade and interiors. The 3,500-seat auditorium was designed by John Eberson, reputed for his “atmospheric” style of theaters. Remembered for showing filmed spectacles like Cecil B. DeMille’s’ The Ten Commandments (1956) to mass audiences from Queens and Western Long Island, the theater yielded to the inevitable in 1977 to be the Tabernacle of Prayer who have renovated and preserved its features.

Most of these palaces were before my time, but those that I did experience (Rivoli, Loews State, Capitol, etc) represented a special and glamorous dress-up evening on the town with a hot date.

Although I’ve never seen a show in any of the grand movie palaces of New York, I’m old enough to remember when a theater contained just one screen, so a father couldn’t send his kids to watch a G-rated film while he opted for an action picture and his wife enjoyed a romantic comedy.

Another great article by Dr. Mariampolski. My late mother often talked about the great movie theaters of New York City. Her sister would often skip school with.a friend to catch a show.

Okay, you led me to a confession of my own: At some point in the 1950s, I was at an appointment with Dr. Lipshitz, the meanest dentist in New York. The one compensation of going to his office in the Times Building was being face-to-face with the smoke rings from the Camel advertising billboard. I didn’t go back to school after that visit like I was supposed to but, instead, ducked into the Paramount Theatre to see Rogers and Hammerstein’s State Fair

.Definitely learned more than I would have at school.Thoroughly enjoyed this!! What a wonderful tribute with beautiful antique postcards! Leave it to Mr Miriampolski to provide us a front row seat into yesteryear only this time into what was our mood elevating fantasy world of escape to a shangrila for a whole nickel, a seated journey into the world of silver clouds with vivid views of our favorite larger than life screen stars starring in slices of life that took so many people out of their own problematic worlds for at least a few hours in these amazingly beautifully marqueed and majestic fantasy castles that was as good… Read more »