Owen Carrollson

The Swamp Angel

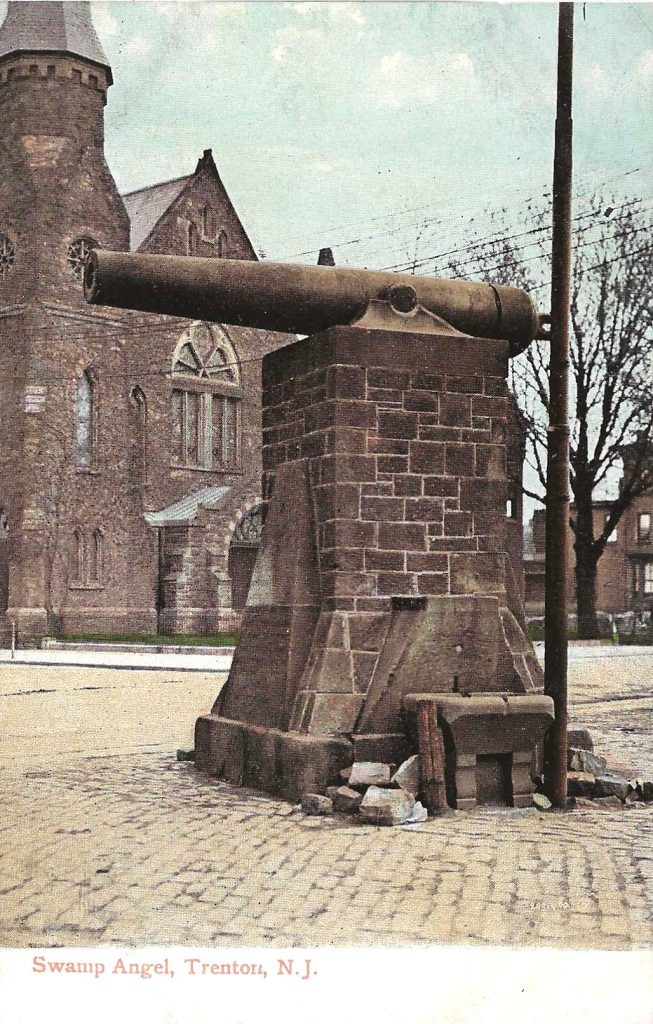

The “Swamp Angel” is not a smiling cherub with rosy cheeks, neither is it a colorful bird that nests in marsh reeds. When you look at the postcard below, it may surprise you to learn that the Swamp Angel is one of the most famous cannons of the Civil War. In August 1863, the Union Army used it to reign terror down on the city of Charleston, South Carolina.

Noted journalist David Martin is quoted, It scared the heck out of the people in Charleston because nobody had ever fired cannons that far before, some of the cannonballs fired by the Swamp Angel traveled over five miles.

Martin continues by quoting General Quincy A. Gilmore’s note to General P. G. T. Beauregard, the Confederate commander of the CSA forces in Charleston, warning, You better surrender or we’re going to shoot at downtown Charleston. It has been recorded that the confederates laughed because such an attack had never happened before.

Born in Ohio in 1825, Q. A. Gillmore was first in his class at West Point; he graduated in 1849. His appointment to the engineers earned him the opportunity to work on the Naval fortifications at Hampton Roads, Virginia. He was promoted to first lieutenant in 1856 and continued to serve in the Union Army until 1888. His death came at age 63; he is buried in the West Point Cemetery.

Gillmore’s work in South Carolina was by comparison a minor accomplishment but it earned him an international reputation as an organizer of siege operations and helped revolutionize the use of naval gunnery.

From General Gilmore’s rather detailed notes we know the following particulars: The Swamp Angel was employed on this occasion as a weapon authorized for use because Charleston was by existing rules of warfare a legitimate target. It was an armed camp. There were fortifications in the city. It was home to a number of munition plants, and its wharves served blockade runners who carried war supplies.

Nevertheless, when truth was told, Gilmore’s and his compatriot’s reasons ran even deeper. Most of the Union saw Charleston as a symbol of rebellion. Charleston was where South Carolinians voted to secede from the union and it was there that the firing on Fort Sumter started the conflict. For most of the Union, Charleston’s destruction was simple retribution.

Gilmore’s notes included the weapons vital data: the weapon had a registry number 6. From that, it was determined through foundry records that the weapon was made at the West Point Foundry, in New York, in 1863 and weighed 16,577 pounds when delivered.

Actual bombardment opened in the morning of August 22, 1863, but preparation had been ongoing for several days before. A platform had been built on Morris Island (in the marshes south of Charleston) with a sandbag parapet to support the Swamp Angel. There are records that cite engineers using 13,000 sandbags and 123 pieces of 15- to 18-inch timbers for the pilings that were sunk into the marsh, and 9,156 feet of 3-inch planking.

Thoroughness was the watchword in preparation. While the platform was built, and the gun was made ready, other details were tended to, such as the work done by gunnery engineer Captain Nathaniel Edwards who took compass readings on St. Michael’s church steeple in downtown Charleston for night firing. (When that happened, and it did happen, it was the first ever “compass-point” aimed assault in wartime.) The bottom line was, whenever Gillmore was ready, the Swamp Angel was ready to fire into Charleston – day or night.

On August 21, General Gillmore received word that the marsh battery was completed and ready to fire. That message prompted the afore mentioned demand that General Beauregard evacuate the city. The note reached Confederate headquarters at 10:45 P.M., but Beauregard was not present. Since the message was unsigned, it was returned for verification, which prompted the Union forces to commence firing. At 1:30 A.M., August 22, the Swamp Angel was aimed by the compass reading taken on St. Michael’s steeple and it fired the first round into the city. Before dawn, the Swamp Angel would send sixteen shells into Charleston.

The shelling continued in the evening of August 23. Twenty additional firings were accomplished but the Swamp Angel exploded at its breech-band on the 36th firing.

The Swamp Angel was not replaced during the Morris Island operation. Gillmore later wrote that he never expected a battlefield victory from the shelling and he came to realize that the shelling of Charleston was meant to hurt an enemy that was much stronger than he expected.

There are several accounts of the onslaught. The best being, The Gate of Hell, the Campaign for Charleston Harbor, 1863, by Stephen R. Wise.

After the war, salvage efforts gathered the remains of the Swamp Angel and its remnants were transported in an 1877 shipment to the Phoenix Iron Works, along the Delaware River in Trenton New Jersey, to be melted.

In a stroke of some very unusual luck two Connecticut Infantry soldiers who had served at Morris Island, South Carolina, during the war recognized it. They reported their find to the state Adjutant General who in turn ordered it to be saved, restored, and exhibited as a relic of war.

Editor’s note: There are several Civil War photographs, 1861-1865, related to the Swamp Angel, in the Library of Congress at Washington, D.C. The catalog date is 1977. The call number is LC-B8156- 35[P&P]).

The article on the Swamp Angel was very interesting. That is real history and I love history. Then explaining how a canon works to my wife along with gun powder and how they made the gun powder. And how they aimed the canon, made me think a little more about the whole process. I really love the Postcard History articles. Keep up the good work.

Great story! Thanks for writing it.

A bit of Civil War history I hadn’t read until today.

Interesting to see cards of and hear some battle history of this gigantic war machine. Thanks.

Kudos to you for offering this article. I really enjoy history, especially U.S history but was not aware of the Swamp Angel.