Timothy Van Staden

Say, ‘Hello Japan”!

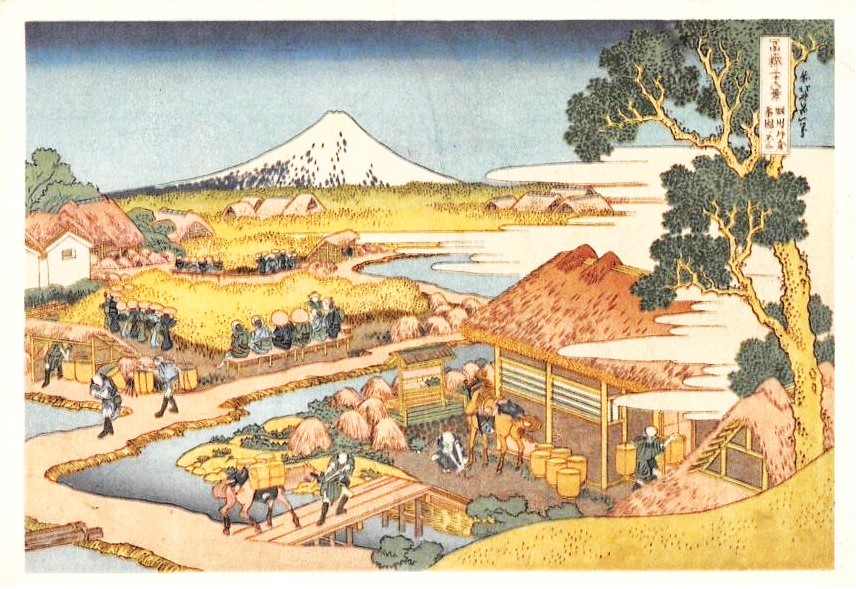

If you have collected postcards for any length of time, it is likely that you have seen this Katsushika Hokusai (1760 – 1849) image many times. Have you ever purchased this card for your collection? I have not, but I have two copies.

Japan is a preferred-tourist destination for many reasons. It is part of the world where culture and tradition stand proudly among modern achievements in technology, science, and medicine. With that said, Japan is also an oasis of art, both traditional and modern, that is honored by every element of society.

Hokusai’s Great Wave of Kanagawa may be the most iconic piece in the history of Asian art. If you look for it with any degree of enthusiasm, you see it on t-shirts, coffee mugs, greeting cards and it appears in these places because it was made to be.

Hokusai, was born in the ancient city of Edo in 1760. As a boy he displayed an unusual talent for artistic renderings of his environment and society. In the nearly ninety years of his life (he died in May of 1849 at age 88) he was the primary representative of the “ukiyo-e” Edo period as a painter and printmaker. He is best known for the woodblock prints of Mount Fuji series.

Hokusai’s Fine Wind, Clear Morning, woodblock print, circa 1830

Mount Fuji is the highest mountain in Japan and is universally recognized by its snowcapped peak. It is located about 65 miles south of Tokyo, Japan’s capital city. It is considered an active volcano, however, there has been no volcanic activity in the area since 1707. The native Japanese refer to the mountain as “Fuji-san,” and pilgrimages to its summit remain a favorite activity since Fuji is the best known among Japan’s three sacred mountain peaks.

Hokusai and his contemporary Hiroshige (nee Andō Tokutarō) are only two of the Japanese artists who have used Mount Fuji as an artistic subject.

Hiroshige’s Fuji

Utagawa Hiroshige, a generation later and very much in the same way, followed Hokusai to the top of the “ukiyo-e” art movement in Japan. At about the same time that Hokusai was working on his woodblocks of Mount Fuji, Hiroshige embarked on a similar woodblock project centered on Japanese landscapes, flora, and fauna. The work he did in that era made him famous and among his most ardent followers was the French impressionist artist, Claude Monet. After his work reached Europe, in the late nineteenth century, the art world expanded to include the Orient. It was then that Hiroshige earned the reputation of being a great master of his tradition and also the last.

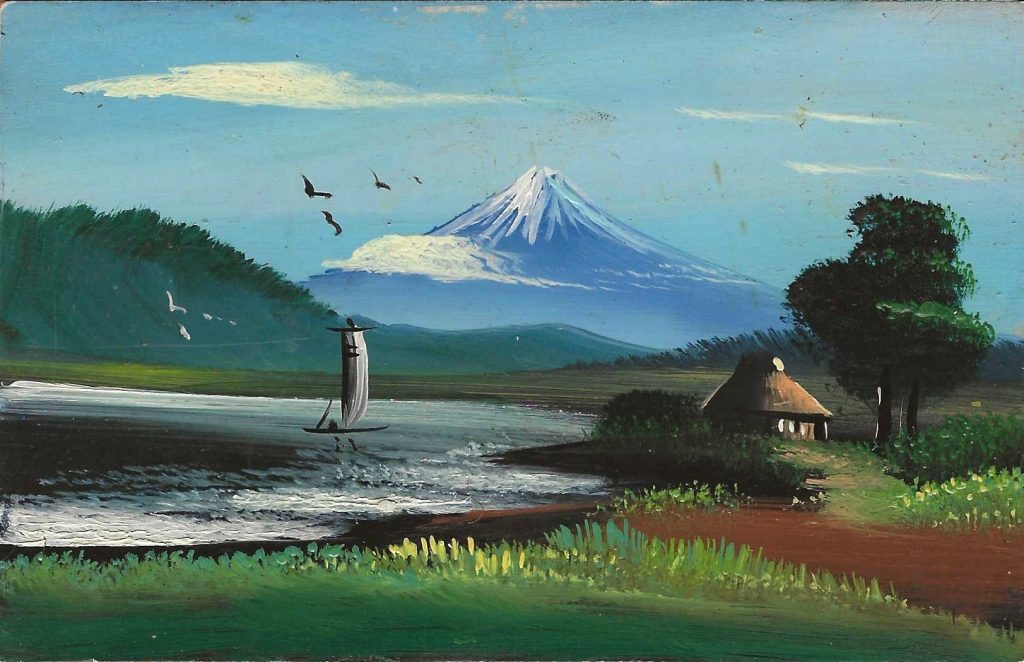

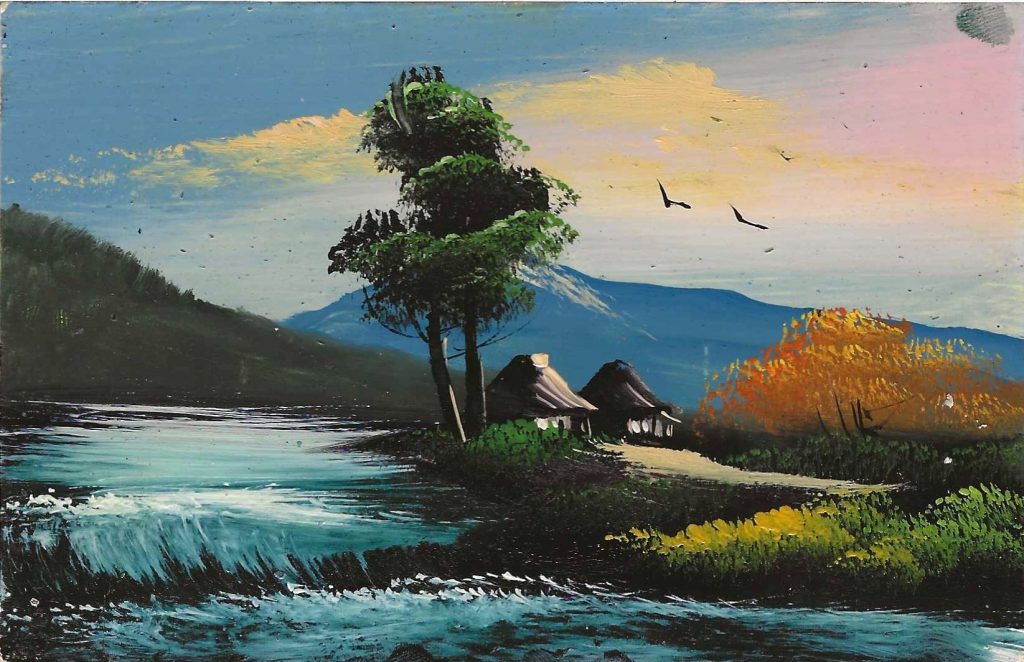

Others in successive generations have followed Hokusai and Hiroshige, but they continue to use Mount Fuji and the exquisite landscapes of the area as their cultural icon and their geographic landmark.

There is, however, one ugly caveat. The extremely high demand for souvenir postcards in the years beyond the opening of a notoriously closed society brought into the picture a gang-studio approach to postcard manufacturing. Hundreds of young artists would be tasked with making hand painted copies of forgotten images done decades before by famous artists. The cards were usually sold without artistic credits, in sets of six with Union Postale Universelle “Carte Postale” backs for the equivalent of ten “American” cents.

|

|

|

|

Today, Japanese postcards are not as popular as they were in the early twentieth century, and then in the late 1940s and ‘50s, but they do represent a fascinating era from a part of the world that remains mysterious and eerie. Together, it can be said, they are cheap, yet beautiful in many ways.

Fascinating. Thank you for this article.

Reading Public Museum has a Wood Block Pint of the first image. I have a booklet with the image on it’s cover. I was having an MRI in Tower Health Hospital and this image was on the overhead ceiling.

Interesting to know. I have a few in the “woodcut” style that I suspect were probably of the “knocked-off” variety but still manage to convey some of the peacefulness of the better ones.

One reason Japanese postcards are not collected more widely may be that the writing on many of them is not even in the Roman alphabet, let alone in English.