Hy Mariampolski

Give My Regards to Broadway:

Act 2 – The Operetta Era

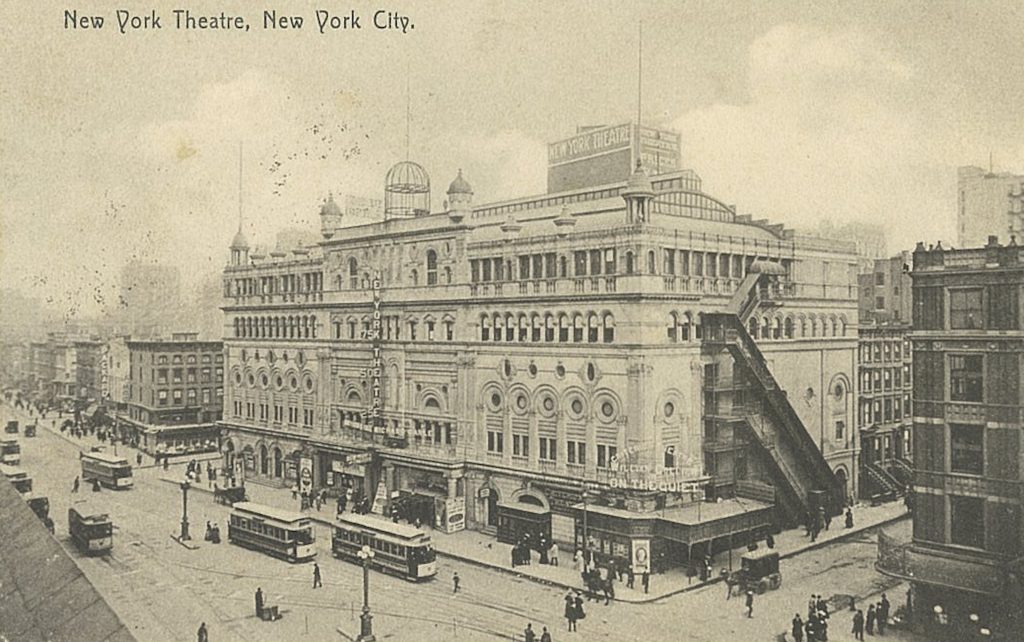

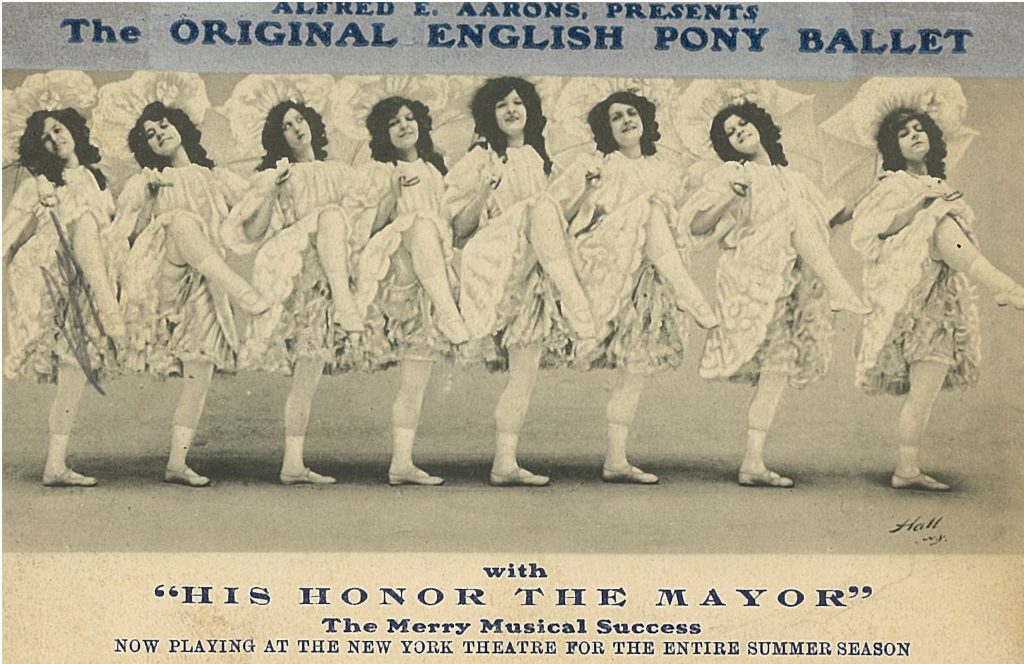

When New York’s Theater District drifted north of 42nd Street it was not shy or halting in the move. One of the brash encroachments was establishing the Olympia Theatre at 1514–16 Broadway at 44th Street, also known as Hammerstein’s Olympia or the New York Theatre. A theatre complex built by impresario Oscar Hammerstein in Longacre Square (later Times Square) it opened in 1895, consisting of a theatre, a music hall, a concert hall, and a roof garden. Later, sections of the structure were substantially remodeled and used for both live theatre and for motion pictures. As a cinema, it was also known at various times as the Vitagraph Theatre and the Criterion Theatre.

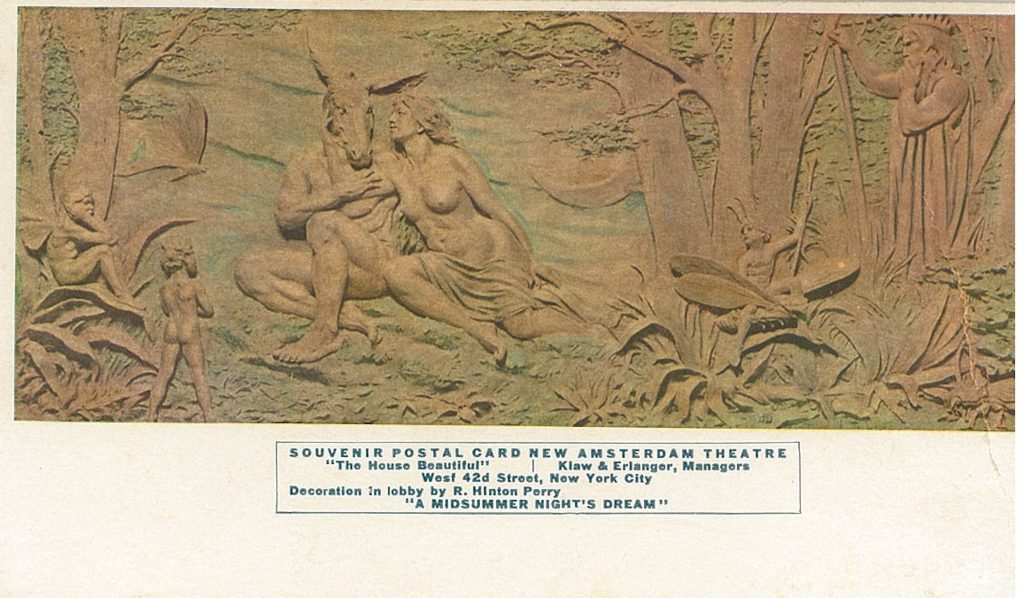

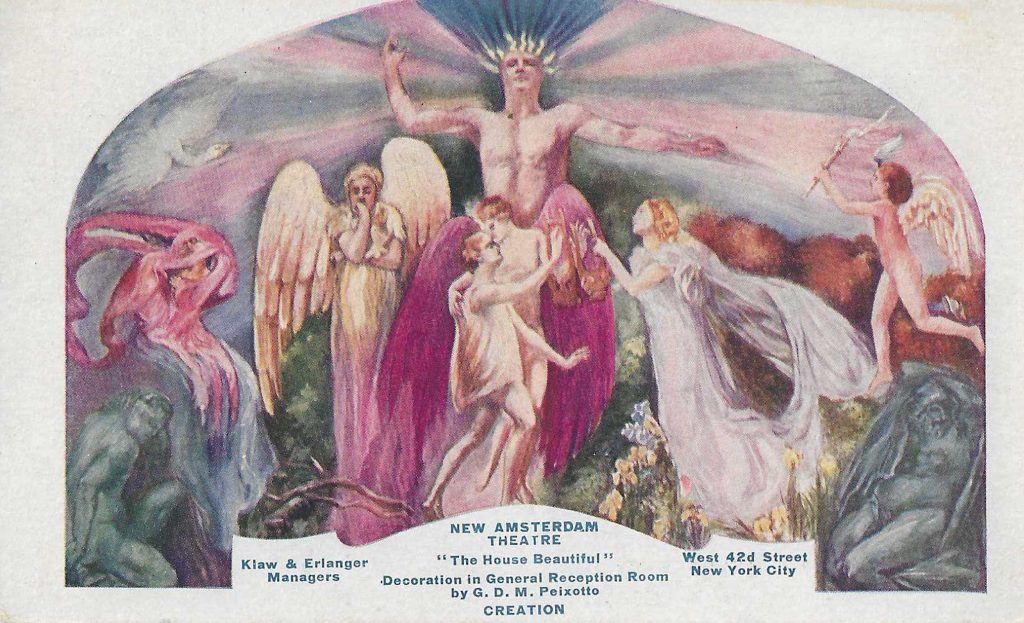

Right on 42nd Street just west of Times Square, the New Amsterdam Theatre has had a unique though checkered history. Brought back to economic viability and artistic success during the renovations of the 1990s, today the venue specializes in live theatrical productions of Walt Disney Company properties such as The Lion King and Mary Poppins. Originally opened in 1903 by Klaw and Erlanger, the building designed by Herts & Tallant with Beaux Arts and Art Nouveau elements, was an engineering marvel when built due to its advanced hydraulics and electrical systems. Although its capacity was slightly smaller at its start, today the theater offers seating for 1,702.

Historic postcard enthusiasts are charmed by the seemingly endless series of promotional cards depicting the theater’s interior decorations and murals that illustrate Shakespearean plays and Wagnerian operas, the history of New York City and various futuristic concepts.

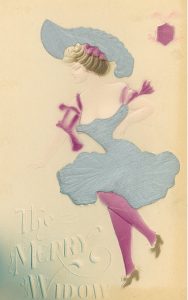

The “house beautiful,” as the theater was nicknamed, experienced breathtaking success with Franz Lehar’s The Merry Widow, the breakout hit of the Operetta Era. Later, from 1913 to 1927, the New Amsterdam hosted the Ziegfeld Follies, an adaptation of vaudeville that incorporated many of their leading acts, including W.C. Fields, Eddie Cantor, and Sophie Tucker. Brought down by the Depression and Broadway’s exhaustion in the 1970s, the glorious New Amsterdam was showing nothing but tawdry kung-fu and pornography films, when it was rescued and reconceived for new audiences and a new era by Disney.

At the turn of the 20th century, American theater could still be described as in its infancy. Even though it was a period of profound development in script, character, and technical theater, most of the action was taking place on the other side of the Atlantic. Henryk Ibsen, Anton Chekhov, and August Strindberg were expressing ideas about realism and honesty in dramatic construction. Dublin-born George Bernard Shaw was shaking the English-speaking theater as he coated his realism with a veneer of political engagement. These playwrights would continue to influence American theatrical development throughout the century.

In the face of European advances, American theater was still in the grip of prudish and sentimental Victorianism despite the rapid expansion of its audience. In New York the burgeoning population growth was due to immigrants who were bringing European sensibilities to their entertainment expectations.

New York was the point of origin of American theater in the 19th century when adaptations of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s melodramatic anti-slavery novel captured Americans’ consciousness and remained tops in popularity even after the Civil War. Racial justice was established as a recurrent theme for many playwrights.

The term “Broadway” became synonymous with New York’s theater district. Playhouse construction coursed for a half-century along Broadway starting downtown and ending up during the postcard era mostly in the 40s. The peculiar formal organization of American theater, which separated theater ownership and production from the creative enterprise of actors and entertainers also was a product of New York. Competitive producers like the Shubert brothers, Klaw and Erlanger, Wood and Savage, guaranteed that the stage would be dominated by financiers operating under the rules of late capitalism.

Perusing postcards published to promote theatrical productions and their protagonists bring insights that help us understand the development of American drama and musicals. The extensive collection of real photo post cards by Rotograph make clear is that the era certainly had its superstars. Maude Adams, appearing as J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan and Shakespearian specialists Julia Marlowe and E.H. Sothern commanded astonishing salaries for their era as well as the perks of theater royalty such as private train cars bringing them home after performances.

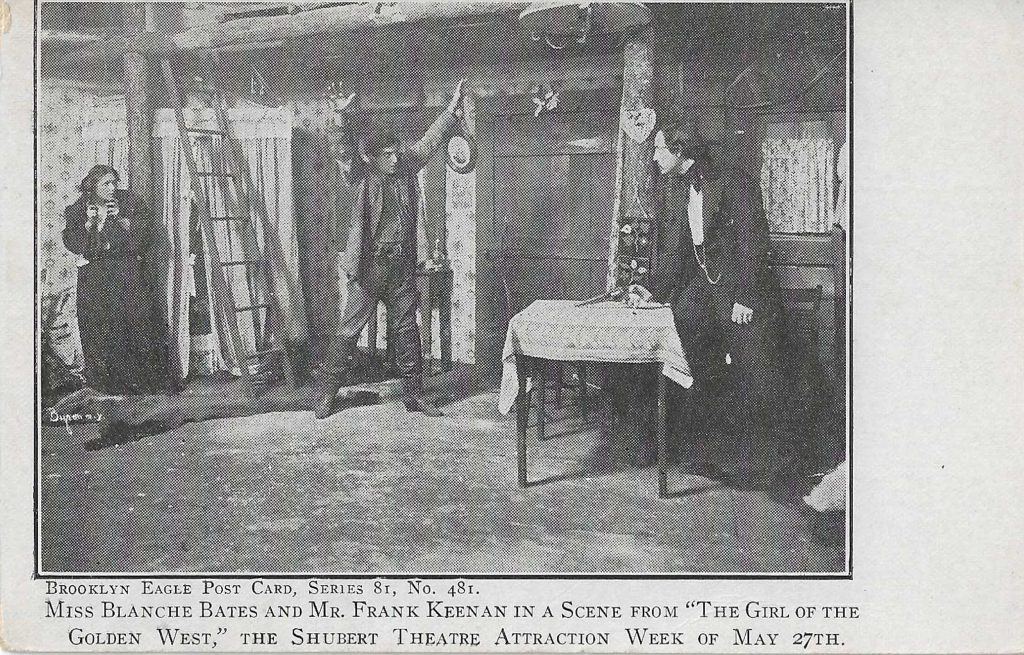

No American playwrights commanded the acclaim of Ibsen or Shaw, however, there were some standouts such as David Belasco whose collaboration with the Italian verismo composer Giacomo Puccini helped create the operatic hits Madama Butterfly and La Fanciulla de West (The Girl of the Golden West.) The latter in 1910 was the first world premiere at New York’s Metropolitan Opera, which commissioned the work. The Met’s leading artists performed – Enrico Caruso as Dick Johnson and Emmy Destinn as Minnie – and the orchestra was conducted by Arturo Toscanini.

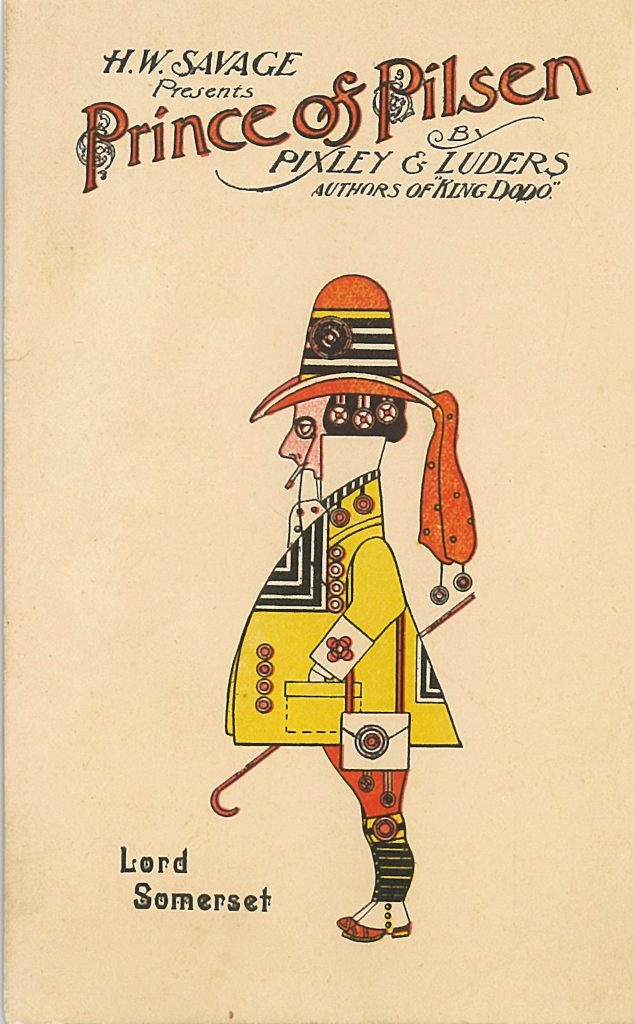

Shakespeare and classical playwrights were well represented on Broadway but otherwise it was a steady diet of sentimental love stories. Nevertheless, audiences were filling up the seats and humming those tunes on their way home. Among the standout productions in 1903 were The Prince of Pilsen with lyrics by Frank Pixley and music by Gustav Lauder, about a Cincinnati brewer lost in a mythical European country and mistaken for the title character. Quite a few drinking songs were sung before that show climaxed.

The Merry Widow by Franz Lehar achieved popular fad status in 1907 with 416 performances following the widowed Sonia cavorting in Paris with Prince Danilo. After this massive record-breaking success, as Brooks Atkinson has said, “no one wanted to wake up from the operetta dream.”

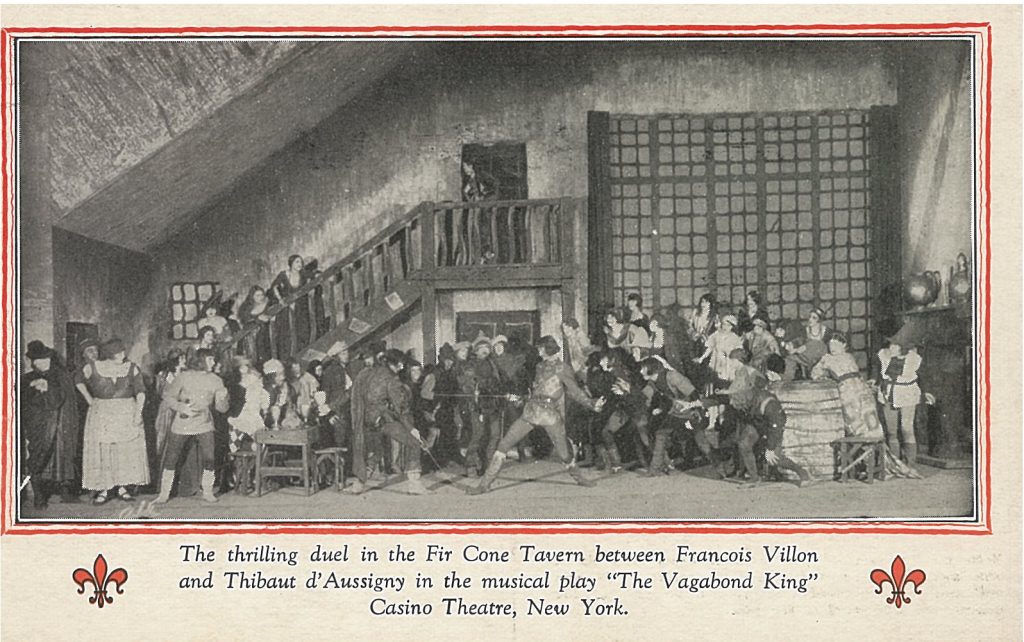

Czech-born Rudolf Friml, trained in composition by Antonin Dvorak and a successful orchestral musician supported by fellow-Czech Emmy Destinn, was recruited in 1912 by a “desperate” Arthur Hammerstein to write several swashbuckling operettas. He created show tunes for productions that are still classics, including Rose Marie and The Vagabond King. Theatrical productions by Lehar and Friml and other Broadway composers of this period, like Victor Herbert and Sigmund Romberg, later achieved breakout hit status when they were made into films. As talkies became a reality in the 1930s, songstress Jeanette MacDonald, often accompanied by Maurice Chevalier or Nelson Eddy, starred in several Oscar-winning successes based on Broadway operettas of this era.

As the Great War was winding down, the operettas were guaranteeing happiness and Broadway was finally starting to look toward the evolution of an American theater. Several significant theaters, such as the New Lyceum, the Cort, and the Winter Garden were coursing their way north of 42nd Street. How far North could the Broadway theater district extend and what would it take to develop a uniquely American theater experience. These issues were on the minds of theatergoers and creative personnel as we move on to the next act of our postcard history of Broadway.

The “Shakspere” spelling on the Teachers College card reminded me that orthography was not standardized (or “standardised”, if you’re British) during Elizabethan times, and that such variants as “Shakespere”, “Shackespeare”, and “Shaxper” can be found in documents that date to the Bard of Avon’s lifetime.

A bit of trivia: The Pennsylvania Railroad’s NY to Chicago “Broadway Limited” was not named after NYC’s Broadway. It referred to the 4-track-wide (broad) way to Chicago, so that this express was not held up by other trains.

Another fascinating insight into the early days of Broadway. Thank u.

The postcard artwork of Lord Somerset in “Prince of Pilsen” is my most favorite postcard for today, what a gem!! Just imagine artists with that kind of imagination back then. I love it.