Dr. Donald T. Matter Jr.

Maud Humphry and Her Art

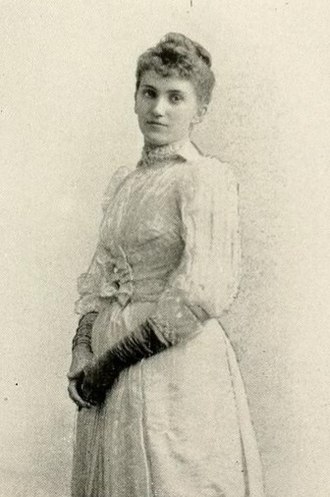

Maud Humphrey, circa 1895

Maud Humphrey was born on March 30, 1868, in Rochester, New York. By age 12 she was already studying art with a family friend and pastor named James H. Dennis. The Humphrey’s home was in the Third Ward – the part of Rochester where the city’s wealthiest and most socially elite families lived. Maud took great pleasure in the prominence of her family origins and chose to use only her maiden name in her professional life. Although Maud suffered with migraine headaches all of her life she maintained a high level of creative productivity. In diaries and from family sources it is suggested that Maud created, in her 60 year career, as many as ten illustrations a week. Some estimates of her career range from 28,000 to 35,000 pieces. The Victorian Era, in which she lived, imposed many limitations on women, but Humphrey was a successful artist in a time when her skills mattered most. It is probable that some of her illustrations have been reproduced in the millions.

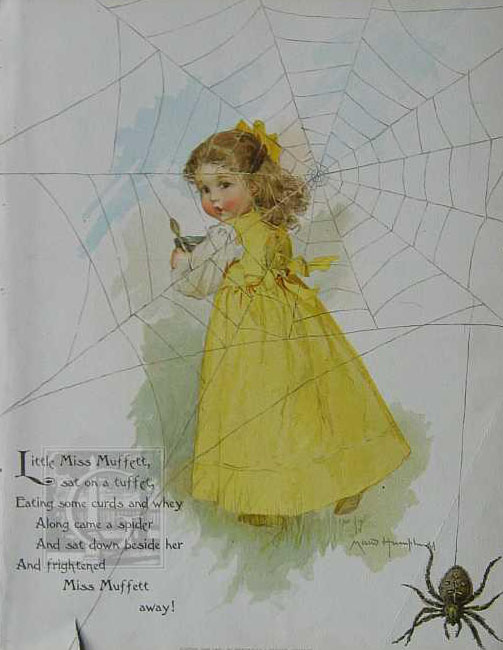

At age 17, Maud began study at the Art Student’s League in New York City, and like many others, she returned there and continued her studies whenever time and circumstances allowed. For much of the following three years she busied herself with greeting card competitions and book illustrating. (Two of Maud’s book illustrations for a publisher’s edition of nursery rhymes may be seen here.)

Some time in 1888 she gave a child’s picture to a friend, who took the picture for framing to the Stokes Company, a New York City art dealership and framing shop. Mr. Stokes was impressed with the work and through some quite tedious correspondence Humphrey agreed to illustrate one single book for Mr. Stokes, but that project turned into and exclusive contract that took every piece of her work for two years.

Maud Humphrey thought it necessary for her to have a unique professional wardrobe and work style. Her studio was always immaculate and she painted standing up, wearing freshly ironed artist aprons or smocks. When at work Maud would dress in shades of gray with white, purple, or pink accents that included lace scarves, bows, and ribbons. She always wore high heeled shoes. She was a tall woman; five feet ten inches, with curly hair and a slender figure.

In 1891 Maud went to Paris for study at the Julian Academy where she participated in oil, watercolor, and illustration classes. It was in Paris that she studied with James McNeil Whistler. By 1893 she had developed a reputation of being a children’s artist and although on rare occasions she did use professional models, most of her work was done using friend’s children in their own playful environments. This genre of her art became known on Madison Avenue as the “Humphrey Baby.”

Art historians ask, “What do these American businesses have in common?” Ivory Soap, Crosman Brothers Flower Seeds, Mellin’s Baby Food Company, Wilkie & Platt Clothiers, Elgin Watch Company, Sunshine Stoves Ranges and Furnaces, Butterick Patterns, Equitable Insurance, Metropolitan Life Insurance and Anheuser-Busch have all used Maud Humphrey’s work in their national brands advertising. (At left is a postcard of a Maud Humphrey illustration done for the Butterick Company – pattern makers who have accommodated generations of American home dress makers. In 1908 this card and several others of similar design were made into a very popular set.)

Humphrey married Dr. Belmont Deforest Bogart, a surgeon specializing in heart and lungs. She was a proud wife and mother and in her very late years attracted more attention as the mother of the actor Humphrey Bogart, than as an artist. Dr. Bogart was of Dutch decent and wealthy from his father’s invention of the process for doing lithography on tin. Maud’s son, Humphrey was the model used for her most famous advertising illustrations – advertisements for the Mellin’s Baby Food Company. Both parents spent a great deal of time at home. Their careers allowed the doctor to practice in the family home and the artist to have a studio with a nursery on the third floor. The household had two maids, a laundress and a cook. Like fashionable families they had a summer cottage at Lake Canandaigua, New York, but this was a 55-acre working farm with manicured lawns and a dock for sailing. The family owned the property until 1915 then sold it for a summer residence on Fire Island. This allowed Humphrey to be closer to her position as art director at The Delineator.

The Bogarts were much affected by the depression (1929-1933), her husband’s dwindling medical practice and failing health, and the literal disappearance of the family fortune, forced them to sell their primary residence and move to a converted brownstone in New York City (not a serious inconvenience since the new home was in the elite and fashionable Upper West Side). Then, more than ever before, Maud’s studio became a sanctuary. After her husband’s death, she was left with thousands of dollars of debt in hospital bills. It was then that she was forced to turn to her son for help. Humphrey was by then a young actor in Hollywood and with only minor difficulty he managed to pay the family debt and chose to move his mother to California. She lived in an apartment on Sunset Boulevard at the Chateau Marmont. This lifestyle was hard for her to accept, but with F. Scott Fitzgerald, Laurence Olivier, and other Hollywood dignitaries and much of the Hollywood glamour crowd buzzing about in the lobby, she gradually changed her opinion. The California sunshine brought many changes in her life, like a daily walk to Schwab’s Drugstore where she would often make a minor and frequently unnecessary purchase and would then return to the Marmont with many on-lookers taking note of her every movement. She would fill her mornings and evenings by painting or drawing in her apartment studio. In those later years, Maud frequently returned to the greeting card as an outlet for her creative talent.

After only five retirement years at the Chateau Marmont, Maud died of pneumonia, a complication of cancer on November 22, 1940. She is buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Los Angeles. Her death certificate lists her as a “housewife.”

It is a sad fact that in the era in which Maude Humphrey worked it was standard publishing practice that original art became the publisher’s property. After any one particular advertising project was finished the art was kept in vaults or storage cabinets until it was no longer cost effective to keep it. When the clean out order was given by the publisher or the advertising editor, pages by the thousands were simply and unceremoniously destroyed. These terrible events account for the relative scarceness of original Humphrey art today.

Another cruel reality is that none of Maude Humphrey’s work was ever intended for postcards. She was never a postcard artist. She was by profession a commercial illustrator who earned nearly $50,000 annually, a colossal sum in her time. It is however a wonderful anomaly that many postcard publishers recognized the popularity of her work and printed her illustrations and advertising art by the millions.

Like so many intelligent, gifted, and talented women that have passed through this world virtually unknown, Maud Humphrey made a wonderful contribution to society with her artwork. She was innovative and also instrumental in paving the way for women of today to succeed in careers they love.

I think someone should petition to have her death certificate changed from, “Housewife” to “Artist”…

This is the most informative article on Maude Humphrey that I have read in years. Thank you

I am the proud owner of a children’s book by Maud Humphrey it’s a patriotic book I don’t have the name it’s in storage but the illustrations are wonderful